The main parties' belief that they can regain far-right voters lost to AUR through nationalist and ultra-conservative discourse might resurrect the ghosts of Romania's past even further instead of letting them go once and for all, Andrei Tiut writes.

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to be a testament that Romanian democracy, while challenged, still functioned.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Like other Eastern European countries, Romania had imposed relatively severe restrictions from the start, which led to a “flattening of the curve” in the first months of the pandemic.

Yet, at some point, and without any instantly apparent reason, things began to unravel.

Exceptions were carved out for some. The prime minister, the minister of health, and other officials were photographed violating the rules they themselves imposed.

While the restrictions actually softened over time, they became harder and harder to understand and, therefore, accept.

As politicians continued to fumble, confidence in the government's decisions collapsed. Vaccination rates declined, and conspiracy theories flourished despite the visibly increasing number of cases and deaths.

The far-right rises to the occasion

Two propaganda forces came to the fore in this period. Firstly, the Archbishop of Tomis took advantage of the initial confusion within the Romanian Orthodox Church to oppose the restrictions and encourage believers to attend liturgy despite legal limitations.

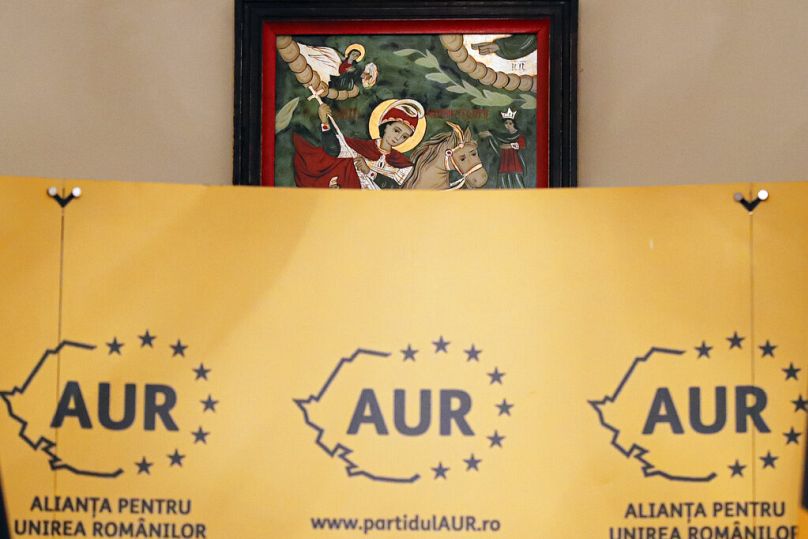

Secondly, a new party called Alliance for the Unity of Romanians or AUR came to the forefront of political debate.

It combines elements of the “unionist” discourse — that is, promoting the unification between Romania and the neighbouring Republic of Moldova — with elements of Christian nationalism with fascist undertones.

The party is led by George Simion, a well-known advocate for the unification between Romania and the Republic of Moldova, and Claudiu Târziu, an apologist for the Romanian fascist period and its historical personalities.

In the December 2020 elections, AUR, which had also brought Diana Șoșoacă — previously the public advocate of the Archbishop of Tomis — to its party lists, scored a surprising 9%.

The party would continue to grow during the pandemic, briefly ranking as the second-strongest party in Romania according to some polls.

Currently, AUR and Șoșoacă's breakaway party SOS together hold around 20% of the vote.

Communist dictatorship spawns sympathy for Romania's fascists

In Romania, the fascist past comes in two flavours.

On the one hand, we have the Legionary Movement, also known as the Iron Guard, which espouses boilerplate fascism, including the cult of death and mystical discourse.

It remains, however, notable for its chaotic and disorganised character, to the point that Hitler himself had to authorise World War II fascist dictator Marshal Ion Antonescu (with whom the Iron Guard shared the government) to eliminate them through a coup.

During the post-war period, Romania's communist dictatorship's persecution of the Iron Guard fed the myth espoused by their supporters today.

After the war, both fascists and democrats were imprisoned by Nicolae Ceaușescu's regime in the same prisons.

They shared the same cells, ate the same food, prayed together to the same God, and many of them died due to the same inhumane treatment.

After the 1989 Revolution, with the help of some right-wing intellectuals, they were rediscovered and promoted together under the label of "saints of the prisons".

'Overly liberal' Soviets make some Romanian communists turn to nationalism

The second legacy is that of Marshal Antonescu. As he took over the full leadership of the state and turned it into a para-fascist personal dictatorship similar to Franco’s Spain or Salazar’s Portugal, Antonescu ordered pogroms and deportations in the occupied territory of the Soviet Union, making Romania infamous as a major actor in the Holocaust.

After the war, he was put on trial for war crimes and executed in 1946.

But, after the initial purge of elements from the old regime, hardline Romanian communists sought to distance themselves from the Soviet Union, whose leaders, from Khrushchev to Gorbachev, could occasionally be too “liberal” for their taste.

To attract the Romanian population to their side, a new ideology aggregated communist propaganda with nationalist elements, turning into what historians call national-communism.

Texts by Marx criticising the Tsarist Empire — ergo, Russia — were used, peppered with elements of the far-right discourse. In this context, certain parts of the memory of Antonescu survived albeit discreetly, for example, in literary works that managed to get past the censors.

In today's Romania, AUR combines and capitalises on both of these traditions.

Football hooliganism, racism, and Nazi apologia

Its charismatic leader, George Simion, first became infamous in the world of football after organising no less than two fan clubs-turned-hooligan groups.

He promoted a nationalist-unionist message that appeared to be tolerant of more radical elements.

While Simion kept his distance from some of the seedier aspects, football stadiums in Romania are known for anti-Roma chants, including occasional calls for the “Antonescu solution” — meaning, pogroms.

Initially, the party had dual leadership: the other president was Claudiu Târziu, a well-known apologist who had tried to defend historical Iron Guard figures against the accusations levelled against them.

They were joined by Șoșoacă, who became well-known in the public eye for her extremely vocal position against pandemic restrictions.

She brings to Romanian politics a volcanic style reminiscent of the nationalist leader Corneliu "Vadim" Tudor — a senator and MEP known for his anti-semitic, homophobic, and racist views who was famously accused of keeping a blacklist of his political enemies to be arrested and persecuted if he ever came to power.

For what it's worth, AUR is more conspiratorial than extremist

With such a pedigree, we might be tempted to consider AUR a new iteration of ultra-nationalism and fascism. However, it is not clear that the party's members and voters would agree.

There are no clear studies of the motivations of AUR's electorate in present-day Romania, but the party's rise did not coincide with any marked worsening of ethnic relations.

The party seems to thrive on socio-economic crises, including the handling of the pandemics and high inflation.

Moreover, Târziu, representing the intellectual and ideological side of the party, seems to have been marginalised, leaving Simion in the driver's seat, whose discourse is more populist and aimed at the “common man”.

Extremist language is still there — a signature brand of the party playing the role of an outsider who is there to iritate mainstream politicians and intellectuals — but the main focus is on fearmongering and anti-Western conspiratorial discourse.

It is more likely to hear AUR members fantasising about how European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will force them to eat insects than to see them requesting a new “final solution”.

Prodded by growing discontent, others turned to imitating AUR

The most worrisome part is not so much reflected in the natural growth of the far right, particularly since the beginning of the war when AUR began having problems reconciling its pro- and anti-Kremlin constituencies.

It is the panic of mainstream politicians who seem to believe that imitating AUR is the key to taking back their electorate.

Starting from December 2022, a series of issues have put Romania in conflict with Austria regarding Romania's entry into the Schengen area and with Ukraine regarding the treatment of minorities and the fate of the Bystroye canal — a deepwater canal on the Danube delta between Romania and the latter.

Additionally, Romanian farmers are going through a crisis that is the combined result of low production, cheap imports from Ukraine, and poor negotiation with the EU regarding financial compensation.

On these issues, with the exception perhaps of grain imports, Romania has arguably legitimate grievances against both Austria — which keeps using Romania's application to the Schengen for its own internal politicking — and Ukraine, which is pushing the limits of international treaties.

We should stop resurrecting the ghosts of Romania's past

Legitimate criticism that could have been expressed in a liberal language focused on the values of the rule of law was, nevertheless, instrumentalised in a nationalist and populist manner by the main political parties.

However, in all instances where research done at the GlobalFocus Centre measured discussions on these subjects in social media, the conversation was dominated authoritatively by AUR, even when one of the governing parties invested money in promoting its messages.

It was, after all, predictable. When major parties normalise extremist discourse, the electorate will usually turn towards the parties from which this discourse originated, choosing the original over the copy.

Anti-Western discourse seems to have calmed down lately, possibly due to pressure from Western partners and almost certainly due to pressure from President Klaus Iohannis.

However, the main parties’ belief that they can regain far-right voters through nationalist and ultra-conservative discourse does not seem to have disappeared entirely.

This, in turn, should be cause for concern that Romanian politics might resurrect the ghosts of the country's past even further instead of letting go of them once and for all.

Andrei Tiut is Programme Director for Democratic Resilience at the Bucharest-based GlobalFocus Centre. Tiut specialises in the Romanian far right and Russian-aligned propaganda.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.