More than 30 World War II-era artworks that were stolen from a museum in Jajce, in central Bosnia, finally found their way back home after a collector purchased them at a Vienna flea market.

A collection of artworks by a distinguished Yugoslav artist — lost in a northwestern Serbian town for 30 years after being looted during the war in Bosnia — has been returned.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The man who came across them in the 1990s recently decided to return them to the museum in Jajce where they had been stolen at the peak of the conflict.

In 1993, Stojan Matić, an art collector from Kovin, purchased more than 30 portraits of Yugoslav Partisan leaders and World War II fighters at a flea market in Vienna.

Some of them were reprinted on everything from postal stamps to school books and engraved on the sides of buildings.

“It was late 1992 or early 1993, someone called me at our apartment in Vienna and said he had something very good to offer me, some works by Bozidar Jakac, that had just arrived from Jajce in Bosnia,” he recalls. At that time, the wars in Bosnia and Croatia were raging.

“The Vienna flea market often has stolen things from all over Europe.”

“When I came home and opened it, there were two portraits of Josip Broz Tito, a portrait of Ivan Ribar, and a portrait of Edvard Kardelj. Each portrait had the signature of the artist and the subject.”

The most valuable paintings in the collection were from World War II, made during a conference convened by the Partisans in central Bosnia in November 1943. The anti-fascist fighters who were trying to push out Nazis and their collaborators met to plan out their new country once the war would end.

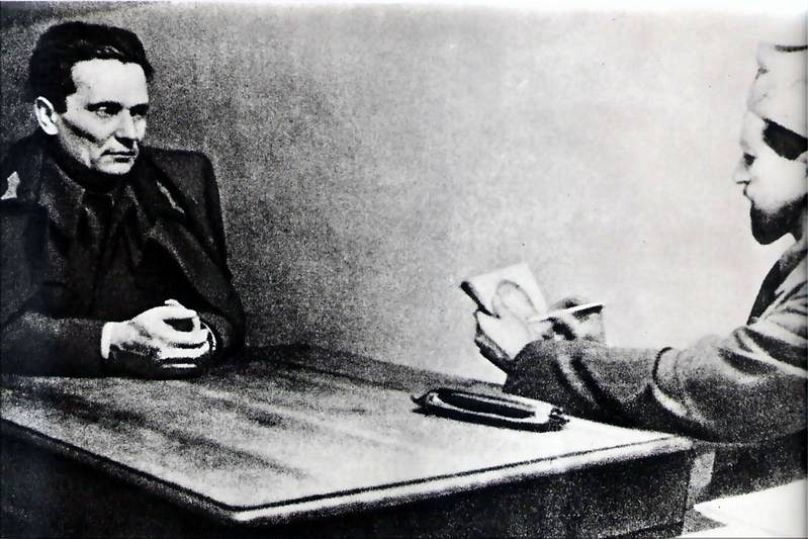

Jakac, a Slovenian realist painter who was also part of the resistance, documented the expressions of the main leaders as they deliberated on the future of a freed nation for their people.

One of the drawings is a famous portrait of the Partisan leader who later became President of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito, drawn in red chalk.

These pieces held both monetary and sentimental value to collectors familiar with Yugoslav history, and Matic briefly entertained the idea of making a quick turnaround on his investment.

“A tycoon of sorts, even though criminal would be a better term, wanted Tito’s portrait to bribe Mira Marković in order to be able to buy a shopping mall in Serbia,” he recalled.

Mira Marković was the spouse of Slobodan Milošević, Serbia’s nationalist leader at the time. Milošević is known regionally and internationally as the man whose politics triggered the bloody war that followed the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

If he had sold the painting to Marković’s friend, the portraits of leaders from fighting for the liberation of oppressed Balkan nations in one war would end up in the hands of those causing the second major war the region had seen within the 20th century.

“When the bombing of Sarajevo began in 1992 and we watched the gruesome scenes from Bosnia in 1992 and 1993, I told my wife we needed to return this,” he told Euronews.

While he pondered on the right way to return the stolen property to the Jajce museum, thousands became engulfed in a war that took over 100,000 lives in Bosnia alone.

“For me, the Bosnians were the biggest Yugoslavs. The various nationalisms from the region tore their country apart,” he emphasises. “And Bosniaks suffered the most in that war of aggression.”

In the end, it took him almost 30 years to find the right way to do it. Along the way, he enlisted the help of a renowned Bosnian actor, Emir Hadžihafizbegović.

The unlikely duo finally handed over the priceless historical artefacts to the museum’s director on November 29 — the day of the principal session in Jajce, and more importantly, Yugoslavia’s main national holiday, Republic Day.

“If I wanted to make a big deal out of it, I would have sold it to the government of Serbia or enabled them to return the artwork and present themselves as great peacemakers – and wash their dirty hands from their participation in the war in Bosnia,” Matić explained.

“I’d probably get media attention from all the biggest outlets in the country. Except I did not want them to use this for a media stunt.”

“So instead I looked for someone on the other side of the river Drina, and found Emir Hadžihafizbegović – an actor my sons are big fans of. I messaged him on Facebook, especially after I had seen a government tabloid call him a Serb-hater, which is absurd.”

“I told him about the artefacts I had, and I told him I have something stolen from your country that belongs to Bosnia.”

Popular portraitist goes guerilla

The estimated market value of the collection today comes out to around 90 thousand euros, mostly due to Jakac’s recent decline in popularity among collectors.

However, the fact that the artworks were made during one of the most celebrated moments in Yugoslav history makes it much more attractive for collectors interested in World War II memorabilia, for one, which could greatly increase the value of the collection.

And while Jakac is not particularly famous outside of the former Yugoslav area, his work is by no means unimportant.

One of the key founders of the Ljubljana Academy of Fine Arts and the organiser of the International Biennal of Graphic Art in the Slovenian capital, Jakac’s keen interest in the avant-garde saw him incorporate elements of expressionism, realism, and symbolism in his work.

He became a popular portraitist, depicting a number of prominent Yugoslavs, including king Peter II of Yugoslavia and the Slovenian poet laureate, France Prešeren. He was also one of the pioneers of Slovenian cinema.

Then, World War II and the Nazi occupying forces reached the southeast European country. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia capitulated within two weeks, as the royal family fled the country to England, and the disjointed royal army, lacking leadership and discipline, surrendered to the German and Italian occupiers in April 1941.

Soon after that, a guerilla anti-fascist movement sprung up all across the country, led by Tito.

Jakac joined the partisan resistance in 1943, and spent his time in the unit depicting the wartime events. Within a couple of months, he received an invitation to be one of Slovenia’s deputies at the conference in Jajce.

There, he spent the time between the sessions drawing portraits of those who played the most important roles during the war and in Yugoslavia’s immediate postwar future, such as Moše Pijade, Edvard Kardelj, or Ivan Ribar.

Sitting in Tito's chair

Emir Hadžihafizbegović said that when he received a message from a certain Stojan Matić in 2019, he was a little hesitant at first.

“Sometimes really important things in life happen in very strange ways,” he told Euronews.

“Stojan wrote me on Facebook to say he was an antiques collector and that several years ago he came across some very valuable documents that are part of Bosnia’s national treasure and he’d like to give it back.”

“It was a very brief message and at first I thought it was a long-lost friend whose name I forgot, who was now pulling my leg.”

“So I hesitated at first and told him I was working on a role for a movie and we can maybe get in touch at a later time. But then I felt lousy about the message and its tone so I said, if you really have something of such value, I’d be happy to pay for your trip to Sarajevo,” he explained.

“We went for dinner and that’s when he showed me the 30-odd drawings by Jakac which were stolen in late 1992, early 1993.”

The two decided that the only proper way to do it would be to return it on the anniversary of the 1943 session that the museum it was looted from is dedicated to. The pandemic meant that it took another two years to be able to hand over the originals in person.

“The handover in Jajce was truly emotional. Stojan was completely shaken by the place where the session was held and when he saw the hall where a country of 25 million people was conceived, this small building 25 metres long and maybe 10 metres wide.”

After the war, the looted and wrecked museum’s main hall was painstakingly restored to its original look from 1943, featuring authentic portraits of the likes of Karl Marx and Winston Churchill, and the actual chairs that the delegates used during the session.

“They let him sit in the actual chair Tito used, which they don’t do for average tourists. Pijade’s chair is there too, as well as Ribar’s.”

But it’s much more than just returning Jakac’s drawings to the place where they belong, Hadžihafizbegović said.

“I think that in the future, Europe and its union will be determined by its cultural identites. It’s the only value system that will determine the value of a society.”

Hadžihafizbegović said that the two are now good friends and that the story was so interesting that he wants to turn it into a feature film.

But future acts similar to Matić’s, where other stolen artefacts would be returned in places plundered by the Yugoslav wars, would mean more than any political agreements between the former belligerents in the war, Hadžihafizbegović believes.

“Since this became public, I keep getting messages from all sides — Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats who are completely fascinated by this story. It’s this elementary human context that is reaffirming the need for us to be close to one another.”

“There’s this last line in this play that I love, Aleksandar Popović’s ‘The Spawning of Carp.’ ’There are two kinds of people: those who are humans and those who are not — all other divisions are false.’ And Matić’s gesture is something that brings back hope that there are good people left in this world we live in, as cliche as that sounds.”

Matić hopes that people in his home country will be equally positive about his gesture, although nationalism continues to be high in the region and this might spark ire in the more radical circles.

“I’m not afraid of someone beating me up or something happening to me because of this,” he said.

“I think that anti-war, pacifist Serbia warmly welcomes something like this, and would do so for other similar gestures.”