Nuremberg: How the world's first war crimes trial revealed the scale of the Nazi Holocaust

When the Nuremberg trial opened on November 20, 1945, it was just six months since Nazi Germany had surrendered and much of the city remained a bombed-out ruin.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

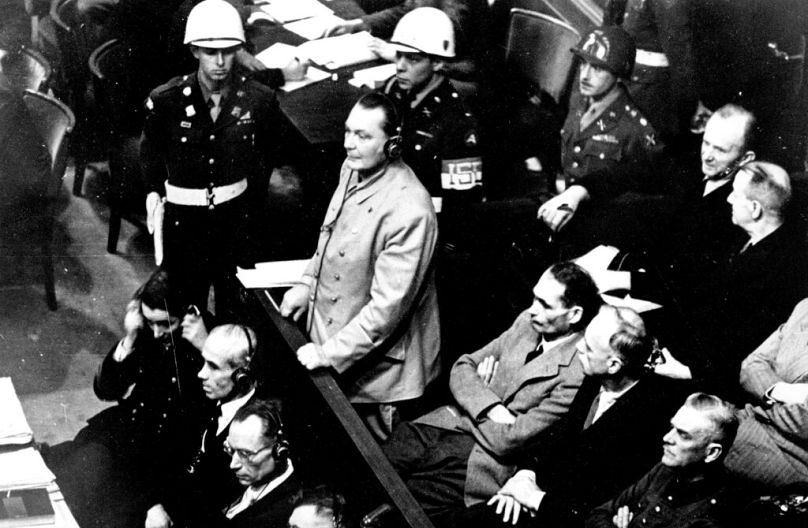

Jointly headed by an American, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, and a Briton, Sir Hartley Shawcross, the trial saw 22 high ranking Nazi officers face trial for war crimes, including two of Hitler’s foremost generals and his second in command, Hermann Göring.

“That four great nations, flushed with history and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that power has ever paid to reason,” Jackson said in his opening statement.

The 22 defendants at Nuremberg represented the highest echelons of Nazi power, including three of the top generals that led the war, Alfred Jodl, Karl Dönitz, and Wilhelm Keitel. The highest-ranking member of the SS was Ernst Kaltenbrunner, while foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Albert Speer, known as Hitler’s architect were among facing trial.

The sentences ranged from 10 years in prison (Dönitz) to death (Keitel, Jodl, von Ribbentrop, and Göring, although he committed suicide before he was due to be hanged). Hess was jailed for life, and died in 1987, while Speer served 20 years, was released and died in 1981.

There were notable exceptions to justice at Nuremberg. Hitler, of course, had committed suicide in April 1945 as the Soviets closed in on his bunker in Berlin, as did Joseph Goebbels, who committed suicide along with his wife after poisoning his six children.

Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, escaped Germany when it fell and ended up in Argentina where, in 1960, he was tracked down by Israeli agents and flown back to Tel Aviv to face trial. He was convicted and executed in 1962.

Nuremberg and the Holocaust

Nuremberg was the first time that much of the world had heard of the atrocities committed during the Holocaust. The Soviet armies had liberated the camps, but the scale of the enslavement and mass murder of millions of European Jews by the Nazis was largely unknown.

In April 1946, Rudolf Höss (not to be confused with Rudolf Hess, who Deputy Fuhrer until 1941) the commander of Auschwitz, took the stand as a witness, explaining with cold calculation how he had started using Zyklon B gas because he did not believe that monoxide was efficient enough and killing people in the gas chambers quickly.

Höss went on to describe the system of deception at Auschwitz that gave new arrivals the impression that they were to be de-loused, and the practice of forcing inmates to write postcards to their families to give the impression they were in a holiday camp and were “well treated.”

William Shirer, a correspondent for CBS News who had covered the rise of Nazi Germany and the early years of the war from Germany, admitted that he was shocked by Höss’ testimony and of the revelations of the atrocities that had occurred against European Jews during Nazi rule.

“He seemed almost anxious to tell his story, both in affidavits for the prosecution and then on the stand. He seemed proud of his achievements as one of the greatest killers of all time,” Shirer wrote in his post-war diaries.

Three months earlier, in January 1946, the former head of the Einsatzgruppen D (one of the paramilitary units responsible for mass killings), Otto Ohlendorf, also appearing as a witness, admitted to murdering 90,000 Jews including the massacre of children as the German army advanced into Ukraine between 1941 and 1942.

“The sheer number of Jews and Soviet commissars done away with by the Einsatzgruppen could not be completely computed at Nuremberg,” Shirer said, adding that the revelations about the Holocaust during the trial were “like a thunderbolt, and left me numb for several days.”

Although they were witnesses and not defendants at Nuremberg, both Hoss and Ohlendorf were later tried and executed for their crimes. Höss, in 1951, was hanged at Auschwitz.

There were some who expressed contrition for what happened under the Third Reich, but most of the defendants when confronted with the facts of the Holocaust claimed either not to have known about it or to have opposed it but been unable to stop it.

Göring, Hitler’s number two during the Third Reich, was noted for his arrogance and swagger during the trial, and completely unrepentant about his anti-semitism.

When he was confronted with the evidence of the mass killings, Göring said he had only known about “isolated cases” and admitted that “excesses” may have occurred. Göring was sentenced to death but committed suicide with cyanide hours before he was due to be hanged.

A number of defences were made, including that only states - and not individuals - could be found guilty of war crimes. It was also argued that the judgment was ‘ex post facto’ - or retroactive - but judges ruled that offences such as murder had been illegal prior to the war.

It was not the first time that there had been an international effort to prosecute war criminals. After World War I, an effort was made to try Kaiser Wilhelm II in an Allied court but Germany’s former leader went into hiding in Holland and could not be extradited.

But in ruling that individuals could be tried for offences carried out during war - and specifically offences against civilians - Nuremberg was a milestone for international law, and when the United Nations set up its own war crimes tribunal in 1993, it was Nuremberg that was its model.

'Victor's justice'

Nuremberg had its critics, even then. There were those who saw it as a victor’s justice, including the writer Rebecca West, who saw it as biased against Germany. Nuremberg was “the place where the world’s enemy was being tried for its sins,” she wrote in the New Yorker in September 1946. It is a criticism that is also levied at international courts and international justice today.

Others pointed out that the Nazis at Nuremberg were chiefly prosecuted for waging a war of aggression, something that had been done before and would be done again but for which - so far, in history - no other nation or individual had faced an actual trial for. They had been punished - in the Treaty of Versailles for example - but individuals had not been tried and executed for crimes.

Others saw a catharsis in what took place at Nuremberg. Years of bitter conflict had torn Europe and the world apart. An ideology had been born that was a debasement, a perversion, of what it was to be human, and it had been believed by millions of people, Hitler’s accomplices. Those who had lived through the war described seeing its architects in the dock at Nuremberg.

“It was in Nuremberg in September 1934 that I got my first glimpse of Adolf Hitler and his henchmen. The men had been so arrogant then and they had become even more so in the ensuing years of triumph,” Shirer recalled in his wartime diaries. “What a contrast to the way they looked in the Nuremberg dock, shabby and down at heel, and beaten.”

Every weekday at 1900 CET, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get an alert for this and other breaking news. It's available on Apple and Android devices.