With a return of heavyweight politicians, a global pandemic, malign external influences and the inauguration of a newly-reformed electoral system, Georgia's parliamentary elections are set to be a crucial test for the country.

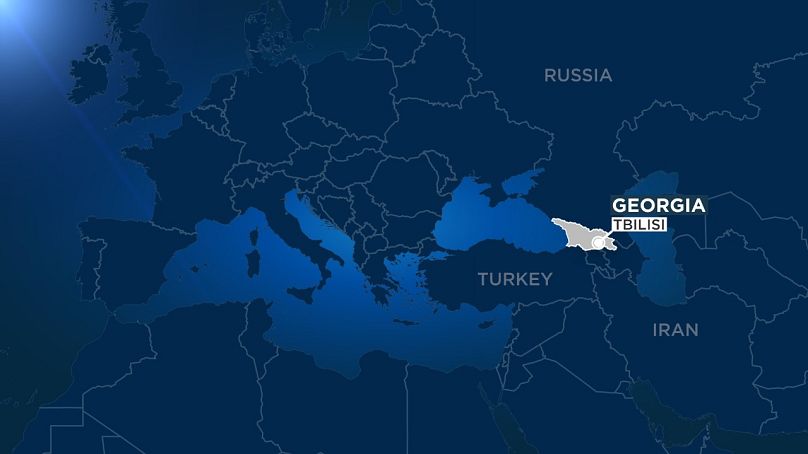

The world's gaze is firmly fixed on the Caucasus region just now after the latest flare-up in Nagorno-Karabakh. Under the cover of the unravelling situation over its southern border, where clashes between Azerbaijani forces and Armenian-backed separatists in the region are becoming ever more intense, parliamentary elections in neighbouring Georgia are managing to escape international scrutiny.

The 2020 elections will be some of the most notable in the country's recent history; not least because they are taking place during the global pandemic, but also because they are the first under a new proportional electoral system that promises to give a platform to a broader range of political voices.

The independent democracy and rights watchdog Freedom House currently lists Georgia as only a partly free country, giving it a combined score of 61 out of 100 based on political rights and civil liberties. While these reforms will no doubt help improve its standing, there are still many potential pitfalls on the road to the country becoming a full, thriving democracy, starting with Saturday's (October 31) parliamentary elections.

New alignment

The newly reformed electoral system was borne out of discontent. As a concession to protesters taking part in widespread anti-government demonstrations in the latter half of 2019, the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party promised a major shake-up of the country's political system.

The result, which gained cross-party agreement, was a reduction of the vote threshold for parties to win seats in parliament from 5 per cent to 1 per cent, as well as a reduction of the number of constituency seats (which were regarded as being more open to bribery and corruption) in favour of more proportional representation.

The changes are significant given that for the past decade, Georgian politics have become polarised between two main political camps: GD and the United National Movement (UNM).

"The new alignment in parliament should at the end of the day be a 'polyphony' and not a 'cacophony'," George Mchedlishvili, an associate professor at the European University in Tbilisi, told Euronews.

"Although it is necessary to realistically assess the current political conditions in Georgia, it will be the year to achieve high-quality parliamentarism. But one-party rule, or two-party rule with a highly unconstructive main opposition party, seems like a worse alternative today."

Return of Misha

Since the country gained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Georgian politics have been dominated by larger-than-life personalities, the most recent being the GD leader, billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili. Crucially, another politician hoping the elections will be a springboard for a political comeback is Mikheil Saakashvili, Georgia's controversial former president.

"Georgia suffers from the overwhelming influence of powerful men: in the 1990s, Shevardnadze, later, Saakashvili, and now Ivanishvili. Powerful politicians divide Georgians more than policies and political parties," Dr Max Fras, Eurasia Democratic Security Network (EDSN) Fellow at Tbilisi's Centre for Social Sciences, told Euronews.

"The electoral reform is a good thing for Georgia’s polarised political system and it will lead to greater representation of many political parties in the parliaments."

While he oversaw unprecedented economic growth and the dismantling of endemic corruption during his two-term presidency, "Misha" - as he is known by supporters and detractors alike - is also remembered for his authoritarian tendencies, something the opposition frequently criticised him for while he was president. Facing charges of embezzlement and abuse of power after leaving office in 2013, charges he still maintains are politically-motivated, he ultimately fled and is now in Ukraine.

While Saakashvili and his UNM party are hoping to solidify their core vote with his return to frontline politics, his polarising effect is unlikely to attract the rest of the electorate to them - or other like-minded parties keen to remove GD from office. Having clearly signalled their displeasure with UNM for selecting Saakashvili as their candidate for prime minister, the opposition, which is far from united, are likely to suffer an electoral setback on Saturday.

"If Georgian voters will see this as an Ivanishvili vs Saakashvili duel yet again, this can weaken the results of the entire opposition spectrum," Fras believes.

"Other opposition parties will move further away from UNM and will be less likely to deal with them, both before the elections - the proportional system favours inter-party deals and they are now less likely - as Saakashvili is one of their 'red lines' and many opposition parties will only cooperate with others if neither Saakashvili nor Ivanishvili are involved."

The opportunity to break the monopoly of strongmen on the reins of power appears to be appealing more and more to the electorate in the run-up to polling day, with the hope being that the new system will usher in a more pluralist political landscape.

"On a more fundamental basis, Georgian society seems to have matured and graduated from the post-Soviet mentality. Much today indicates that most of the people want to see institutions-based coalition government rather than a one-party system headed by a sole leader whom society sees as a saviour," says Mchedlishvili.

"Thus Georgia might be on the cusp of a fundamental shift in its political culture and arrangement, and, given Saakashvili’s authoritarian inclinations, his reappearance on Georgia’s political firmament will probably rob the country of this historic opportunity."

External pressures

Like many former Soviet countries in the region, Georgia is not immune to malign influence from foreign actors, most notably Russia. Having fought a short-lived war in August 2008, Georgia continues to view its larger neighbour and former Soviet sister republic with suspicion, not least because of its continued military occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two rogue regions in Russia's orbit which broke away from Georgia in 2008.

"Russia has inflicted so much harm on Georgia over the past 30-32 years that there is virtually no family unaffected by Moscow’s perfidies," argues Mchedlishvili.

"The current tactics of creeping annexation, whereby on occasions hundreds of yards of additional Georgian territory near the occupation line end up under Russian control, or that of abducting Georgian citizens (on trumped-up charges of 'crossing the state border of South Ossetia') with a subsequent release for a $200-500 ransom only scares the Georgians off and renders the pro-western choice a security necessity."

With an ever-growing portfolio of foreign engagements and entanglements - not least Syria, the Donbas in Ukraine, Belarus, Transnistria in Moldova and more - Russia's head is somewhat turned away from the current political machinations in Georgia.

While elections in the past have been marred, in one way or another, by foreign interference, it is hoped this year's parliamentary elections will pass without any significant intervention, according to Fras.

"External actors indeed usually play a significant role in Georgian elections, but are unlikely to be a major role in the 2020 election," he told Euronews. "Big players in the region are now too busy with the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict to commit significant resources to the Georgian election, so other external interventions are unlikely."

Conversely, it was foreign interference that acted as a catalyst for electoral reforms, precipitated by anti-government protests that started in July 2019. Demonstrations took place after a visiting Russian politician, Sergei Gavrilov delivered a speech in Russian to Georgian MPs from a chair reserved by protocol for the head of parliament.

Over 200 people were injured in the subsequent clashes that erupted in the capital Tbilisi. As well as carrying Georgian and EU flags, protesters carried placards reading "Russia is an occupier" in reference to Russia's presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Protests took place throughout the remainder of 2019 demanding that electoral reforms set to be implemented in 2024 were brought forward, something the GD government vehemently opposed at the time.

Winners and losers

While the election itself is being lauded as a progressive step, the outcome of Saturday's vote is difficult to predict. As was the hope when putting the reforms in place, the latest opinion polls show a shattering of the current duopoly, though GD still maintains a lead over main rivals UNM and other opposition parties. If GD is successful in securing a third term, however, it could well stall Georgia's democratic transition.

"If GD wins a clear parliamentary majority, we will see them grabbing more power in all state institutions; there is a risk of an overall worsening of the democratic consolidation process in Georgia," argues Fras.

"Any move towards greater pluralism benefits Georgia. This is not to say that it will be smooth sailing after the elections. The ruling GD can fail to secure an outright majority and will have to co-opt a coalition partner. Most opposition parties are either strongly anti-Saakashvili or anti-Ivanishvili - it will be hard to find common ground."

He notes that while GD made some progress in its first term in office, efforts to advance various democratic reforms have ultimately stalled during their current term.

The potential for GD to further frustrate the process if returned to office is a point that Fras and Mchedlishvili both agree on.

"The electoral success of Georgian Dream will imply the delay by another four years of the transformation of Georgia into institutional democracy, with more than one political force calling the shots, genuine checks and balances and depoliticised security and law enforcement agencies," says Mchedlishvili.

"In a nutshell, the victory of GD (or UNM for that matter) with minimal political weight of truly novel political forces, distinct from both, would mean that Georgia will stay in the current illiberal democracy limbo."

Maintaining the status quo in Georgian politics is more likely to solicit the unwanted attentions of the Kremlin. Any post-election instability is an opportunity to be exploited, as has been evidenced in the past with Russian advances into previously uncontested Georgian territory in a bid to derail its pro-West trajectory.

"Russia is likely to lose out geopolitically in the current Nagorno-Karabakh war and may want to try to recoup some of this lost capital in other countries of the region," Fras contends. "Georgia remains permanently exposed and vulnerable to creeping 'borderisation' in occupied Abkhazia and Ossetia, and Russian meddling in Georgian politics."

On the other hand, while Russia's attention is likely to revert back to Georgia to some degree, the country's course towards becoming a more European-centric nation is unlikely to be averted, in no small part to the confirmed allegiances of politicians of all creeds. It will not be a question of whether Russia can gain ground in the election, therefore; it will be more a question of whether Georgia's distracted western allies will potentially lose some of their influence.

"Georgia’s western path seems as firm as ever, and the biggest hurdle might be the insufficient engagement of the West, be it the US, EU, NATO, or major European countries," says Mchedlishvili. "These actors seem to be too busy with their elections, political problems and raging pandemics to seriously and judiciously assist EU and NATO-aspiring Georgia."

Every weekday at 1900 CET, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get an alert for this and other breaking news. It's available on Apple and Android devices.