The region of Schleswig voted 100 years ago on whether to remain with Germany or join Denmark, which ultimately led to a split.

This year is being remembered as the centenary of redrawing borders in one part of Northern Europe, with Monday marking 100 years since the people in the region of Schleswig voted either to remain with Germany or to join Denmark.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It is a year of happiness for the Danes - who eventually saw the reunification of South Jutland (North Schleswig) - and are marking the occasion with an event this week in Aabenraa.

But it is also one of loss for Germany, which was depleted of the northernmost part of its region.

So - what was this territorial dispute and what can we learn today in the century that has since passed?

Prussian rule

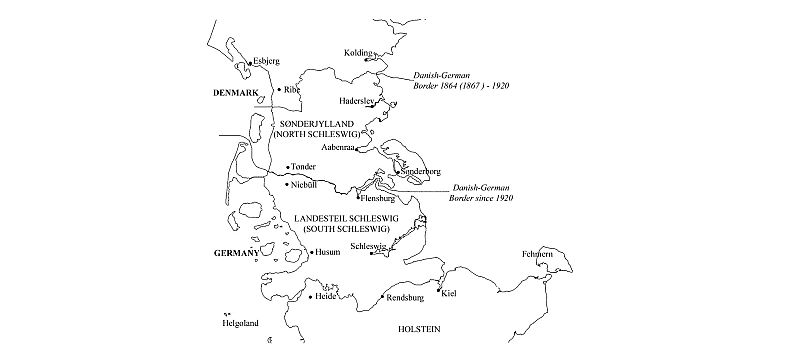

Schleswig was once controlled by Prussia - now part of a united Germany - following territorial wars in 1848 and 1864.

This set the southern Danish border close to the seaport of Kolding, while northern Prussia was in the town of Haderslav.

It stayed this way until the defeat of the Germans in the First World War, when it was decided that those living in Schleswig should be able to decide their own fates.

The region was then split into two zones - North Schleswig and Central Schleswig respectively - to have two referendums on whether to become Danish or to remain German.

The first ballot, held in Zone 1 on February 10, 1920, saw a majority of voters choose Denmark, while the second ballot a month later in Zone 2 saw a majority side with Germany.

As a result, the national borders were redrawn, and, by June 1920, the region of Schleswig was officially split in two.

It was marked by the then Danish king, Christian X, who rode a white horse on July 10 of the same year across the old border into what is known today as South Jutland in southern Denmark.

Central Schleswig, meanwhile, became part of today's Schleswig-Holstein region in northern Germany.

'A loss' or 'a lost daughter who came home'?

For the Danes, this anniversary is marked as a happy one, like "the lost daughter that came home," according to Martin Klatt, an associate professor in the Centre for Border Region Studies at the University of Southern Denmark.

But in Germany, he told Euronews over the phone, "it is a little different."

He said: "It was a loss. The region was divided."

'A great insecurity'

For both countries at the time it was also a period of "great insecurity", Klatt added, as during the 1920s and 30s, some in Denmark wanted to continue deepening its new border, while Germany wanted it back.

Klatt also pointed out that despite two referendums showing a clear majority split from the northern Schleswig alignment with Denmark - and the south with Germany - there were still national minorities to consider.

"You have to remember around 20-25% of the population in each referendum didn’t end up in the country they wanted to," Klatt said.

"There was a lot of unrest on the border."

This was further exacerbated during the Nazi occupation of Denmark, and later with the threat of the Soviet Union in what was then East Germany.

"Denmark didn’t want it all to happen again and therefore dropped neutrality and joined NATO," Klatt said.

"When it became clear that West Germany would also join NATO, there was no more room for border revision."

As a result, West Germany and Denmark came together to accommodate national minorities on either side of the border, which can still be seen today with Danish schools and churches on the German side.

Klatt said: "It gave them cultural autonomy...and it became a good model to integrate people who didn't get the border they voted for."

What can this border dispute teach us today?

In comparing the situation with the UK's recent departure from the European Union - another leave or remain conundrum - Klatt suggested there were takeaways from the Schleswig division.

Firstly, are the national identification and social issues for those who didn't get the "border" they voted for.

The second, Klatt said, which "are very often underrated", are the economic issues.

"It took 40-45 years for the people to settle with the situation in 1920," he said, adding: "It took 70 years to accommodate with the economic situation."

Speaking specifically about Schleswig, he said: "There was an economic catastrophe in the 1920s and 30s."

"Before the vote it was one economically migrated region and socially integrated."

"In the 1800s, it was one of the richest areas of the Danish monarchy...Flensburg, the biggest city of the region, used to be the second most important city in the Danish state.

"Now it is just a small town.

"It lost half of its hinterland - where people came in to trade and send children to school."

He added: "The southern part of the border became one of the poorest areas of West Germany until the 1990s."

READ MORE:

- Denmark restores passport checks on German border

- Denmark builds border fence with Germany to keep infected wild boar away

- Denmark to conduct checks at border with Sweden to counter cross-border crime

The regional economy was therefore "stagnated" and didn't develop as fast as other cities during these border uncertainties, he said.

"It was very difficult to start initiatives for the region’s economy. This lasted until the 1970s until Denmark became part of the European community - when it became the part of Denmark closest to that community."

He continued: "This is still very valid today. With Schengen, people cross [the border] much more for different activities."

'Overcoming borders'

The border narrative still has its problems, Klatt said, pointing toward border checks amid the migrant crisis and a "symbolic" fence built to keep out disease-carrying wild boar.

But overall, the narrative has changed to one of "overcoming borders" and developing relations on each side, he said.

Today, there is a cross-border Euroregion known as Sønderjylland-Schleswig, which conveys just that.