Who's to blame for fake news? Whether you read stories, write stories or appear in stories you might want to start by looking in the mirror.

In this post-truth era we live in, the media, the science community, and the politicians together face increasing distrust from the public. But why?

The issue was on everyone’s lips at the first ever European Parliament Science week from February 5 to 7, only a few weeks ahead of the EU elections.

Trust in politicians is at historic lows and in the labyrinth of corridors and meeting rooms at the European Parliament (EP), it is easy to feel a sense of perplexity, not to say real panic, among the politicians.

“There’s a hybrid media war financed by foreign powers, by armies. We need to protect democracy. We are all very nervous about it,” warned Dr. Paul Rübig, first vice-chair of the EP Panel for the Future of Science and Technology (STOA).

The STOA and de EU Commission’s Joint Research Center organize every year the event “Science Meets Parliament”, bringing together politicians and scientists to narrow the gaps between the two.

Politicians: how democratic is our democracy?

Politics and politicians are often the first victims of fake news and mistrust but sometimes also the first offenders.

In his speech at the plenary session of the 2019 EU Science Week, European political heavyweight Jerzy Buzek highlighted “emotions” as one of the key issues of our time both for politicians and scientists (and of course for the messengers, the media).

“Emotions are taking over facts and the truth, the wave is growing,” he warned, wondering “What we didn't see coming”.

European Commissioner Tibor Navracsics urged for bridges to be built between the isolated communities of scientists and politicians, one of the themes of the annual event, held by the STOA and EU Commission’s Joint Research Center since 2015.

Then the author of “People vs. Democracy”, professor Yascha Mounk issued his own warning.

In short: the EU democracy is not democratic enough. Politicians have to reform, stay away from corruption, get closer to the people, in summary: change, because populist movements are identifying and exposing real problems “but they propose fake solutions”, Mounk said.

He noted that younger generations have forgotten the blights on the continent during the 20th century with memories of the Soviet Union and fascism fading.

The science community: caged in their labs?

Are scientists responsible as well? Who’s failing when a few climate change deniers do better in spreading their message than the large majority of the scientific community? Or when thousands of citizens decide to swap vaccination for alternative medicines?

Cardiologist Tim Chico, one of the scientists chosen to “shadow” an MEP during the EP Science Week, acknowledges that scientists hold some responsibility because their methods are intrinsically cautious: “That’s a very confusing and complicated message for a citizen to understand, they have very little time... They want to know what is the answer”.

One of the youngest researchers invited to meet an MEP, neurologist Caspar M.Schwiedrzik, says he believes experts are facing a growing anti-scientific sentiment.

“For too long we haven’t been interested enough in communicating to the general public about what we do, why we do it, and why it’s important.”

The STOA’s MEP-Scientist pairing scheme put brings together MEP’s and scientists together since 2007 so that both can learn from each other.

The media: scapegoat or Trojan horse?

During the three day forum, the European Science-Media Hub organized a workshop specifically for journalists on how to tackle misinformation and disinformation in science.

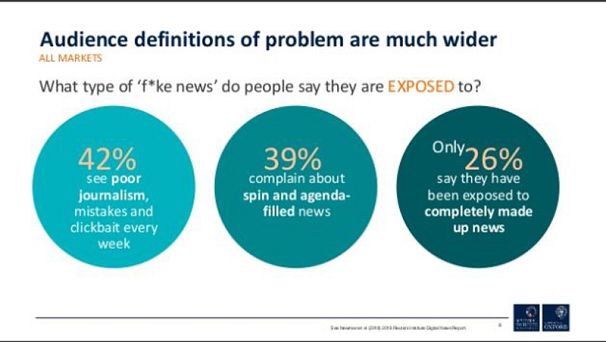

Main speaker Scott Brennen highlighted a striking finding of the 2018 Digital News Report by Reuters news agency: the audience see poor and/or biased journalism as a far much bigger problem than the infamous fake news.

Brennen suggested that a crisis prompted by competition for advertising from Google and Facebook has forced media to produce more, more quickly, leading to an echo chamber recirculating reports from press releases or based on other media.

“We see a growing distrust toward elites and this plays also a role in the media echo: Populist ideas circulate widely, there is also increasing distrust in institutions,” he told the recently launched Science Media Hub Website.

Guido Romeo, who presented his data journalism project Factful in Brussels thinks that the public is keen to get high-quality reporting and is even happy to pay for it but the “media industry is downsizing newsrooms to cut costs without a clear strategy to improve reporting quality and trust in the brand.”

Also read: How can Europe tackle fake news in the digital age?

He cited the recent series of job cuts at US news outlets like Gannet, Buzzfeed and Vice.

The EU is doing the right thing to avoid “truth laws”, which he characterised as very dangerous for the freedom of speech, and putting more pressure on the big platforms (Google, Facebook, Twitter) to counter fake news and misinformation, according to Romeo.

Indeed, data shows that 80% of the traffic to news websites comes from Google and Facebook. In other words, it’s their algorithms that decide what you might read.

The challenges of reporting science

Science journalists face even more difficult challenges to regain the public's trust.

During the debates, experts and journalists pointed the finger at scientists and reporters who have been willing to put their names, often in return for generous payment, to work serving the interests of companies and lobby groups, giving a sense of bias to the public.

Another issue facing the profession is that science journalists find it hard to convince editors that their stories deserve to be published ahead of more sensational or “urgent” news.

Vera Novais, science reporter for Portugal’s Observador, said she enjoys good relations with her editors but agrees that newsrooms have shrunk to such an extent that the few specialized journalists remaining are stretched so thin that they have little time for quality reporting.

Hungarian science editor Johanna Rácz called for journalists to be more rigorous and check facts with experts ahead of publication but she also urged education for audiences around "media literacy" to enable them to navigate a world filled with cyber misinformation.