More than 1,900 people have been killed or injured in eastern Ukraine by landmines or other unexploded ordnance. This makes the region one of the most dangerous areas for civilians in the world. Euronews explored how Ukrainians are coming to terms with living next to the danger.

“I am not afraid,” says 80 year-old Lidiya Korolyova as she walks across a snow-covered field to check on a suspicious object. It might be a landmine, lying in wait among the trees not far from her village of Ozerne in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine. When she first noticed it in 2014, she also saw a tripwire in the local forest while picking mushrooms. If she had triggered it without noticing, it would have detonated and probably taken her life.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In the past four and a half years, since the beginning of the ongoing armed conflict between Ukraine and Russian-backed separatists, around 1,900 people have been killed or injured in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions by landmines or other types of unexploded ordnance.

Civilians account for 42% of the victims.

Over 2 million Ukrainians, including 220,000 children, are risking their lives every day conducting their normal daily activities in the areas infested by landmines and other deadly remnants of war, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). This situation makes Ukraine’s east one of the most dangerous areas for civilians in the world.

Both on the frontline and in the areas that are no longer under direct fire, this silent killer remains, threatening children and teenagers who walk to school or play outside and locals who pick mushrooms, gather firewood or work on the land.

Mykola Zadorozhniy, is a neighbour of the mushroom-picker Korolyova who works as a security guard at the local water pumping station. He remembers finding unexploded ammunition near his workplace and home.

“I have seen two “Grads” (122 mm rockets) in the forest. And just here...near the oak tree, we found a device from an under-barrel grenade launcher. Deminers came and took it away”, he remembers.

An even closer brush with death came when Mykola was working in the fields: “I was sowing sunflower seeds, and I could obviously see the tracks left by my tractor. I looked back and saw a 70-centimetre missile lying there, it was right between the tracks from the seeding machine. Emergency responders came and took a picture of it. The next day it was taken away.”

Less than €3 to lay, almost €1,000 to remove

The villagers told about their findings of suspicious objects to experts from The HALO Trust - the largest of the humanitarian operators in east Ukraine engaged in mine clearance. Alongside two other organisations - the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action and the Danish Demining Group - it works under the approval of the Ukrainian government and is financially supported by a number of European Union countries: Germany, Norway, Finland, the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic as well as the US State Department.

Experts say it costs around €2.5 to lay a mine but around €900 to clear it. After the end of the conflict, Ukraine will need at least 15 years to clear anti-personnel, anti-tank mines, unexploded missiles and other explosive remnants of war. This is only a prediction: the security situation does not allow any of the three NGOs to operate either directly on the line of contact, nor in territories occupied by the separatists. And that’s where the situation might be worst.

“We have now established that there are 200 minefields across the Luhansk and Donetsk region, and there are obviously much more than that. The security situation prevents us from accessing the densest contaminated areas along the line of contact,” says HALO Trust regional director for Europe Nick Smart in an interview. Nevertheless, he continues, “We have been successful recently in accessing the 15 kilometre buffer zone from the line of contact. We are getting into highest impacted communities along those areas.”

Hand demining is a meticulous investigation of every centimetre of a flat surface, conducted by a deminer equipped with detectors and other tools. Machine clearance serves as an alternative for when manual work is not possible or ineffective: on a hill, a mound, pit or densely contaminated area.

Euronews was able to watch as a fully armoured front loader rechecked one such place - a former military position.

First, the vehicle with a single operator inside excavates the soil. For security reasons, no one else can be around at this stage of its work, observers are confined to a bunker 100 metres away.

Then the loader brings the soil to inspection areas. There it is manually checked by the deminers. When a detector is triggered, the deminer isolates the signal, marks it, and starts digging for the potentially dangerous element.

Most of the mine-clearance works are weather-sensitive: when the ground is deeply frozen - excavation is impossible, searches for the tripwire are suspended during times of snow.

Nevertheless, as the seasons advance, the work continues. The local population is impatient for the demining to finish and rumours abound as to why the process takes so long - some say the deminers are digging for historical treasures, others think they are preparing new defence fortifications for an escalation in the conflict.

‘Guests become afraid, they freeze’

The villagers have clearly not recovered from what the war has brought to their lives, but they have learned to live with it.

“When I receive guests, my colleagues from other regions, they see all these signs of mined territories, they become very afraid, they freeze,” Lyubov Filonenko, village leader at Kryva Luka says cheerfully.

“And I start telling them that we are living our normal lives! Of course, we follow the safety rules, but there is no reason to be so afraid. We had the cases of journalists refusing to film, refusing to move any further when they saw the warning signs of mines in the fields,” she adds.

In Svatove, in the neighbouring Luhansk region, manual mine clearance is underway. The location make the headlines in the Ukrainian and international news back in October 2015 when a massive explosion ripped through a local ammunition warehouse.

Three thousand five hundred tonnes of ammunition was detonated at the depot and the damage was spread over 20 kilometres, damaging thousands of houses, multi-storey buildings and other infrastructure.

Now, amid temperatures around minus 10 degrees Celsius and piercing wind, deminers are exploring every centimetre of a long marked strip of land to clear it of ammunition that didn’t explode. The explosives expert inspects the land with a detector and when it is triggered, he marks the spot and starts excavation of a potentially dangerous element. After one strip is cleared, another is marked and the process continues.

On average, a mine clearance expert can cover from 10 to 40 square metres per day, depending on the method or weather conditions.

Usually, the team consists of 13 members: a team leader, his assistant, a driver, two paramedics and seven deminers. It takes at least five weeks to train for the job. Most of the deminers are recruited from the local communities.

At first, many were reluctant to take up a job seen as so dangerous, but community work and the positive experience of those who did take up the task helped convince others. Now around 15% of The Halo Trust deminers are women. Humanitarian deminers operating in Ukraine boast of never having had a single serious accident.

Deminers earn around 380 euros a month - above average salary in the region.

“In Ukraine so far we have encountered anti-vehicle anti-tank mines TM-62, both metal and so-called plastic and different types of explosive remnants of war: different types, such as projectiles of different calibers, fuses, grenades, mortars, and signal mines. No anti-personnel blast mines were found but we have seen reports in the media about people seeing them on the line of contact. All the mines found in the fields were designed in Soviet era,” says Yuri Shahramanyan, project manager at the HALO Trust.

We found that the TM-62 type are the most common mines in the east of Ukraine.

Training the population

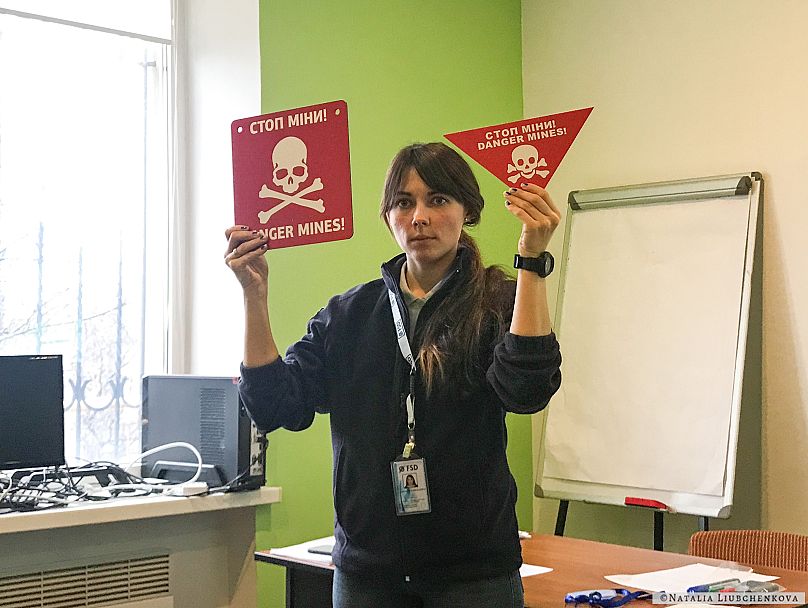

Explosive elements can be well hidden not only in the fields but also in toys, mobile phones or any other unexpected objects. Explaining to the local population how to behave in a potentially dangerous area or how to act if some gets injured is another way to save lives. The experts of Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD), and their colleagues from another two organisations, travel around the region to give classes on the risks the mines pose. This is an important element that helped to decrease mine-related casualties from its peak three years ago. The organisation is mainly funded by the Canadian government and UNICEF. It already reached out to 170,000 people.

“When we started our operation in 2015 we had done a lot of work regarding kids and now we changed our focal point to adults,” says Olena Krivova from FSD. "And our target audience are people who meet the threat of unexploded ordnance while conducting their duties on a daily basis: electrical company workers, farmers, water company workers…”

Until 2014 the possibility of war was something unimaginable for people who live in eastern Ukraine, so they knew very little about explosives or weapons.. During one lesson an office employee discovered she should not have touched an unexploded missile that landed at her backyard.

The tractor drivers from a big farming business located near Mariupol know that anti-vehicle mines can be activated only by at least 150 kilograms of weight. Yet they’ve been told that no one should take a risk of walking on those mines, as another much more sensitive detonator might be hidden underneath it, locals know it as a mine with a “surprise”.

Petro Ziborov, a regional director of agriculture firm “Agrotis” recalls: “In the fields we have found ammunition and very serious ammunition. And that’s why it was not a waste of time to remind workers once again about what might be lying in wait for them and can lead to irreparable damage.”

This 360-degree video was shot with a GoPro Fusion