An inspector general's report finds unencrypted thumb drives, classified servers without locks on them and unrepaired computer bugs going back to 1990.

Cybersecurity lapses as basic as neglecting to encrypt classified flash drives and failing to put physical locks on critical computer servers leave the United States vulnerable to deadly missile attacks, the Defense Department's internal watchdog says in a new report.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The report, dated Dec. 10 but not made public until Friday, sums up eight months of investigation of the nation's ballistic missile defense system by the Pentagon's Office of Inspector General, or IG.

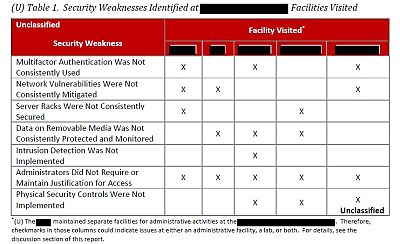

The audit examined five of the 104 Defense Department facilities that manage ballistic missile defense systems and technical information.

The facilities aren't identified in the heavily redacted 44-page report. But the report makes numerous specific references to programs involving the Army, the Navy and the Missile Defense Agency.

"The Army, Navy and MDA did not protect networks and systems that process, store and transmit [ballistic missile defense] technical information from unauthorized access and use," the declassified report concludes.

The shortcomings could lead to the disclosure of "critical details that compromise the integrity, confidentiality and availability of [ballistic missile defense] technical information," it says. Twice, it warns that such disclosure "could allow U.S. adversaries to circumvent [ballistic missile defense] capabilities, leaving the United States vulnerable to deadly missile attacks."

The audit found failures in at least three of the seven security factors under review at all five facilities.

Perhaps most troubling, the audit found that network administrators at three of the five facilities didn't stay on top of known vulnerabilities on classified networks, even those that were flagged as immediately and potentially severe by U.S. Cyber Command.

One vulnerability flagged as critical as long ago as 1990 still hadn't been addressed by the time the IG's office reviewed it in April, according to the audit. The potential consequences of exploiting that vulnerability are redacted in the report.

Some of the facilities fell short in implementing extremely basic cybersecurity measures, like installing security cameras to monitor who goes in and out of facilities that maintain ballistic missile defense information, or making sure that access to computer servers distributing classified information was restricted only to people who had an approved reason and clearance to work with them, according to the audit.

In some cases, there weren't even locks on the doors to the rooms housing the servers, it found. In others, the server rooms may have been locked — but the keys to the locks were kept in unlocked filing cabinets. The data center manager at one of the facilities told investigators that he didn't know server racks and keys were supposed to be secured, the report said.

Investigators also found that employees and contractors were allowed to take classified data with them on removable media like thumb drives without proper authorization. That's how Edward Snowden, then a contractor for the National Security Agency, is believed to have stolen thousands of extraordinarily sensitive government secrets in 2013.

Security

Despite regulations mandating that even unclassified sensitive information transported on removable media must be encrypted, "less than 1 percent of controlled unclassified information stored on removable media" was encrypted at two of the five facilities, the report said.

It said the security manager at one of the facilities told investigators that encryption wasn't enforced because the facility used "legacy systems" — computer-speak for old and outdated hardware and software — that couldn't handle encryption, which any computer you buy today can handle with ease.

Other officials "stated that they were not aware of a requirement or a capability for encrypting removable media," it said.

Such basic failures mean systems that store, process and transmit ballistic missile defense technical data "are vulnerable to cyberattacks, data breaches, data loss and manipulation and unauthorized disclosure of technical information," the IG's office said. And that leaves the United States "vulnerable to missile attacks that threaten the safety of U.S. citizens and critical infrastructure."

The investigation was ordered by Congress last year after Navy Vice Adm. J.D. Syring, then the director of the Missile Defense Agency, expressed concern to Congress about the potential threat to ballistic missile defense information in April 2016.

Time and again, the audit found critical security failures that were the result, to a great extent, of lack of judgment or knowledge by individual employees and managers.

That squares with Syring's testimony before a House subcommittee 2½ years ago, when he said the Missile Defense Agency was working hard to shore up cybersecurity specifically in the areas of "individual human performance and accountability."

The report is just the latest but among the most alarming of a string of internal findings going back more than a decade that the U.S. defense infrastructure is deeply vulnerable to cyberattacks.

The Defense Department disclosed in 2011 that 24,000 files containing Pentagon data were stolen from a defense industry computer network in a single intrusion — one of the government's largest losses of sensitive data before Snowden.

Just two months ago, the Government Accountability Office found that Defense Department weapons programs have been slow to protect systems reliant on computer networks and software, leaving them vulnerable to cyberattacks from both within and outside the country.

In one case, it said, "it took a two-person test team just one hour to gain initial access to a weapon system and one day to gain full control of the system they were testing."