Kim Jong Un has already demonstrated that he has a credible nuclear deterrent and recently said the test site had "completed its mission."

SEOUL, South Korea — North Korea's promise to shut down its main nuclear weapons test site by the end of May is a significant symbolic gesture, but the move will have little impact on Kim Jong Un's existing nuclear and ballistic missile programs, according to experts.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The North Korean leader agreed to close the Punggye-ri nuclear test site during his summit with South Korean President Moon Jae-in, Moon's office announced Sunday.

Kim and Moon also issued a joint declaration Friday promising the "complete denuclearization" of the Korean Peninsula by the end of 2018.

What precisely that means has yet to be determined, but the closure of testing facilities such as Punggye-ri would almost certainly be required under even a loose interpretation of denuclearization.

Pyongyang has already demonstrated that it has a credible nuclear deterrent, and the dismantling of Punggye-ri will not affect any weapons it already possesses.

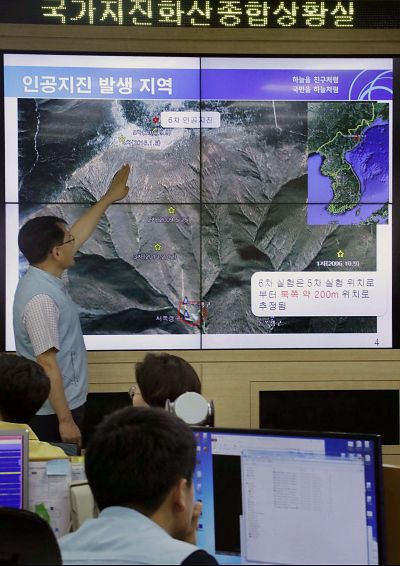

The ongoing utility of Punggye-ri is also unclear. Numerous analysts have concluded, based on satellite photos taken before and after a nuclear test carried out by North Korea in September, that portions of the site had collapsed and were no longer useful. Pyongyang claimed it was the successful demonstration of a hydrogen bomb.

"If reports are true that the tunnels have collapsed, then the test site would be useless for future nuclear tests anyway, so it would just be a symbolic gesture to close it down," said Duyeon Kim, visiting senior fellow at the Korean Peninsula Future Forum. "It's not a serious or sincere gesture to denuclearize."

The possible closure of Punggye-ri was telegraphed by Kim Jong Un nearly a week before his summit with Moon.

"We no longer need any nuclear tests, mid-range and intercontinental ballistic rocket tests, and … the nuclear test site in the northern area has also completed its mission," the dictator said in a statement on the state-run Korean Central News Agency on April 21.

Kim Jong Un claims to have developed an intercontinental ballistic missile that's capable of reaching the U.S. mainland.

In his New Year's Day address, Kim Jong Un claimed that "a nuclear button is always on my desk" and the "entire United States is within range of our nuclear weapons." However, analysts say that based on the current evidence it's hard to prove or debunk North Korea's claim that it could hit targets such as New York or Washington.

If Punggye-ri were shuttered permanently, it may have an impact on North Korea's ability to conduct further testing in the short term, but wouldn't substantially impact their existing weapons program.

"I wouldn't be surprised if they are already digging a new test site or if they decide to forego explosive tests" and instead carry out nuclear tests in labs, Duyeon Kim said. "Advanced nuclear states don't need to conduct explosive tests after a certain point, so Pyongyang might be trying to show it is a part of that nuclear club."

In September, Punggye-ri was the site of North Korea's sixth and most powerful test.

Independent experts continue to debate the type and the size of the weapon used during that test, but the U.S. Air Force Technical Applications Center, which monitors and assesses nuclear activity worldwide, reportedly estimated the weapon's magnitude to have been between 70-280 kilotons.

Such a weapon would be as much as 18 times more devastating than the atomic weapon used to destroy Hiroshima in 1945.

“Do we really want to go to 2030 with North Korea’s ability to conduct a nuclear strike against the United States being an open question?”

On Friday, Kim said he was determined to "proactively and aggressively" provide a verification process for denuclearization.

Kim also said he would invite international inspectors, foreign experts and media — including from the United States — to witness the shuttering of the Punggye-ri test site, according to details released by South Korea's presidential office.

Officials from the International Atomic Energy Agency told NBC News from Geneva that their organization "stands ready" to assist.

Jeffrey Lewis, the director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program for the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, said the closure of Punggye-ri was "of limited value, but it's not meaningless."

He added: "I would compare it to the blowing up of the cooling tower at Yongbyon in 2008."

As part of an international agreement reached that year under talks involving the U.S., South Korea, North Korea, Japan, China and Russia, North Korea conducted a high-profile demolition of a portion of its nuclear production facilities at Yongbyon, paid for by the Bush administration.

Less than a year later, the facility resumed production of nuclear materials.

The details released Sunday are the latest in a steady succession of developments holding out the promise of a swift de-escalation of tensions on the Korean Peninsula.

A friendly and carefully choreographed summit between the leaders of the two Koreas on Friday accelerated the turnaround in bellicose rhetoric, ballistic missile and nuclear tests, and tense military posturing that has characterized the past year in the region.

Apparent advances in North Korea's ballistic missile technology, coupled with the possibility that the country had successfully developed a hydrogen bomb, left American policymakers concerned that Pyongyang now possessed a nuclear-equipped missile capable of reaching major population centers in the continental United States.

The date and location of a proposed summit between Kim Jong Un and President Donald Trump — who until recently have been engaged in a war of words — have yet to be confirmed.

However, the North Korean leader said that when he meets with Trump, the American president would learn that he is "not the kind of person" who would launch a nuclear missile toward the U.S., South Korea's presidential office said. Since taking power in 2011, Kim Jong Un has repeatedly threatened to destroy South Korea and the U.S.

Questions also remain about what happens if such high-level diplomacy fails. The Trump administration has asserted that "military options" remain on the table to deal with North Korea's nuclear program.

"Had we resolved this in 2005, we would be better off today?" asked Bruce Bennett, a senior defense researcher at RAND Corporation who focuses on security issues related to North Korea. "Do we really want to go to 2030 with North Korea's ability to conduct a nuclear strike against the United States being an open question?"