Exclusive: It was meant to be the key plank in Brussels’ fight to show it was dealing with the migrant crisis unfolding on Europe’s doorstep.

Exclusive: It was meant to be the key plank in Brussels’ fight to show it was dealing with the migrant crisis unfolding on Europe’s doorstep.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

With bodies piling up in the Mediterranean and wave-after-wave of would-be refugees moving up northwards from Greece, the European Commission (EC) was under pressure to act last summer.

It announced plans on September 9, 2015, to ease pressure on the worst-hit countries by resettling refugees from Italy, Greece and Hungary, to elsewhere in the European Union.

The proposals involved resettling 160,000 refugees, a drop in the ocean compared with the 1.25-million people who applied for asylum in the EU last year.

As EC chief Jean-Claude Juncker said at the time, it was about showing ‘European solidarity’ and ‘collective courage’.

But, a year on, just 4,500 of the 160,000 have been resettled, Euronews can reveal.

John Dalhuisen, Amnesty International’s Europe director told Euronews: “The abject failure by European leaders to resettle refugees exposes a flagrant lack of commitment of EU countries to their obligations and a troubling lack of solidarity both between member states and with refugees.

“Refugees should be distributed fairly to all member states of the EU.

Europe should be accepting far larger numbers of accept refugees for resettlement and offer other legal pathways of admission, such as family reunification or humanitarian visas. Ultimately, the solution boils down to more responsibility-sharing within the EU and internationally.”

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says the delays are leaving some refugees stranded for up to a year in Greece and contributing to overcrowded and inadequate accommodation centres.

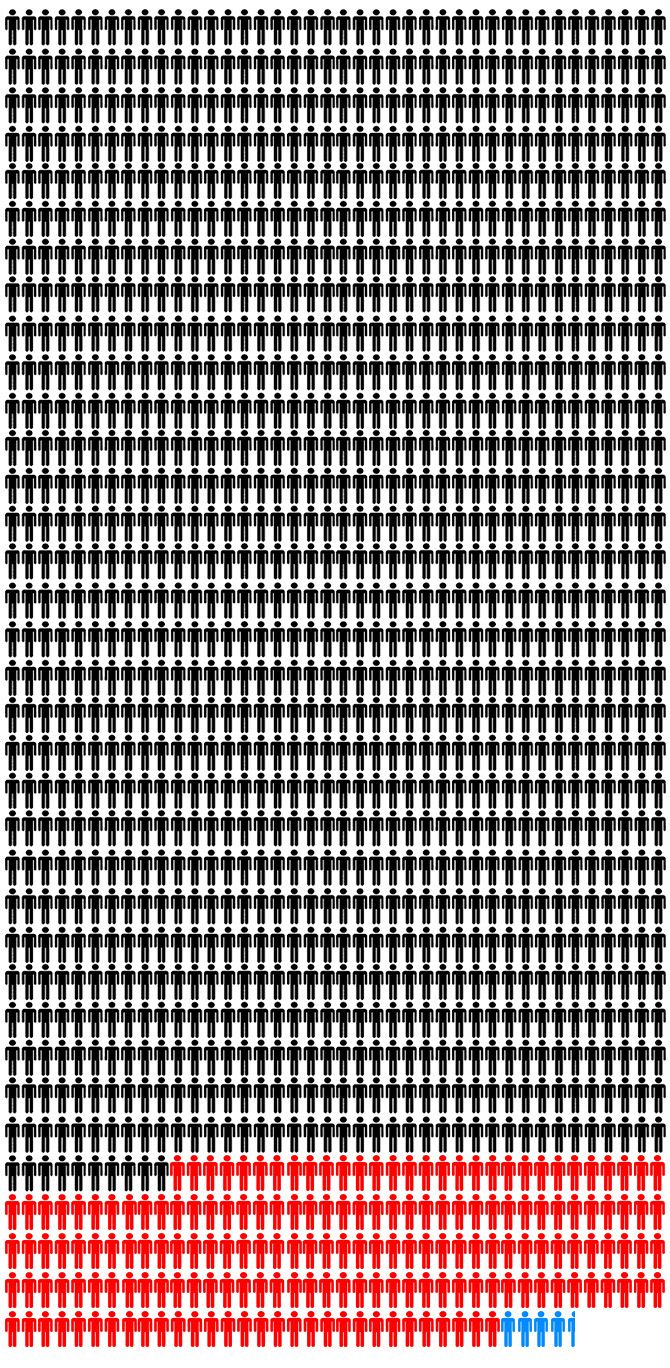

Putting it in perspective: the EU’s ‘failed’ refugee plan

This infographic illustrates total refugee applications in the EU last year (black), compared against how many the EC wanted to resettle (red), and how many have been resettled (blue).

Each stick person in the infographic is equal to 1,000 refugees.

What went wrong?

The major problem has been the reluctance of EU states to accept the number of refugees allocated to them, said Eugenio Ambrosi, director of IOM’s EU office.

But, he added, there has also been infrastructure problems in Greece in terms of processing asylum requests, meaning they have struggled to provide a supply line of refugees to be resettled elsewhere in the EU.

“When it comes to implementation I think the numbers speak for themselves,” he told Euronews. “The programme was supposed to be over two years, which means, if you want to be medical about it, 80,000 should have been relocated in the first year. We are very, very far from that.

“The implementation has been to some extent disappointing, even if over the last few months there has been a sharp increase.”

Ambrosi said there were 8,000 refugees currently waiting to be resettled from Greece, with a further 27,000 in the pre-registration phase.

But, he added, the delays mean there is a ‘huge risk’ those enrolled in the programme will give up and disappear off the radar.

“The longer it takes to move the caseload, the more you clog the system, in terms of reception, housing facilities and assistance in Greece and Italy, because you continue to have a large number of people that still need to be taken care of,” he said.

“You also risk to create a difficult situation in the places where the migrants are staying because you are unable to inform them in a correct and trustworthy manner what is going to happen to them. They enroll on the programme for relocation and then you are in the hands of the receiving state to let you know in a reasonable time whether the person has been accepted or not. In the meantime, we are all in a limbo. You risk creating a lot of tension in these centres.”

Professor Luc Bovens, deputy director of the migration studies unit at the London School of Economics, told Euronews: “Obviously, the pace of the relocation scheme is currently much too slow and this is also for a lack of political will.

“But the problem is not just one of recalcitrant member states: hotspots need to be put in place for reception and registration, experts are needed to man these hotspots, we need a willingness from new arrivals to register and to apply for relocation, and we need to make sure that there is uptake on the side of the applicants to go to the place where they have been relocated to and to prevent that there will be secondary movement to more favoured locations.”

Who have been the most reluctant EU countries?

Figures on how many refugees each EU state has helped resettle has thrown up some surprises.

Germany, for example, which has been one of the most open countries to refugees and migrants, has taken in 62 of its 27,536 quota.

Even the best-performing countries, Finland and Malta, have only taken in around a third of their quotas.

Poland and Austria have not taken in any, while Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland and Slovakia have resettled less than 1 percent of their allocations.

This infographic shows EU countries’ compliance rate with the resettlement plan – the proportion of each state’s refugee quota that has been fulfilled.

The UK and Denmark are exempt. Hungary and Poland have declined to take part.

How could the scheme have worked better?

Ambrosi says the scheme should have been introduced earlier and made mandatory quicker.

But Philip Grech, a postdoctoral researcher at Chair of Negotiation and Conflict Management at ETH Zurich, thinks it should have instead been more progressive.

“Similar to climate negotiations, these schemes work best when we work them bottom-up, at least in the beginning,” said Dr Grech, who also been critical of the formula used to decide how many refugees each EU state should take.

“You get a coalition of willing parties going first and you try to create more and more buy-in progressively by trying to get more parties on board.

“However, imposing quotas for reallocation from above was bound to meet with a lot of resistance. So there is a certain trade-off: how much ‘top-down’ are the member states willing to accept.

“It’s interesting too that the resistance against mandatory quotas comes both from the right and the left.

“The right wants to restrict immigration and insists on sovereignty. The left does not like to see people treated as numbers and wants free movement of people.”

What is the view from Brussels?

The European Commission, perhaps recognising the system needs reforming, is now offering a way out for EU states reluctant to take resettled refugees.

It has proposed member states make a 250,000 euro ‘solidarity payment’ for each refugee it refuses to take.

Asked about the lack of progress in resettling refugees, an EC spokeswoman said: “The Commission is currently redoubling its efforts to strengthen the relocation process in Greece and Italy and maintain political pressure on Member States. Commissioner Avramopoulos contacted all Member States on 5 August, highlighting that the relocation process, overall, needs to be accelerated further and all Member States need to live up to the commitments taken in the relevant Council Decisions and to urgently provide an adequate response by engaging more actively and regularly on relocation from both Greece and Italy.”