In the latest in a series of articles on how World War II changed the countries that fought it, Mark Davis looks at Britain, which emerged from the conflict victorious but at great cost to its people and its position of power in the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

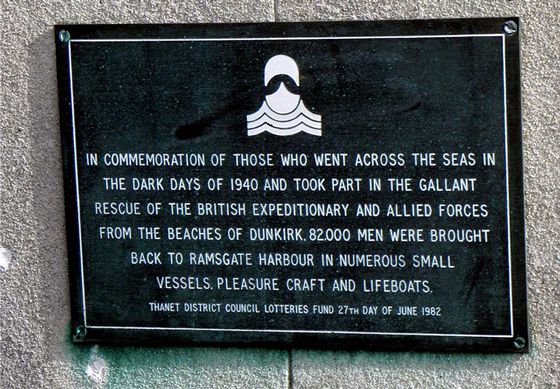

The ‘Miracle’ of Dunkirk

On May 10, 1940 two things happened to really kick-start the war: German forces invaded France and the Benelux countries and Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and wartime leader of the United Kingdom. A week later it was already becoming clear that the Germans would seize control of France after what Churchill described as a “colossal military disaster”. Churchill’s only option was to try and evacuate as many British, Belgian and French soldiers stuck in northern France as possible before they were overwhelmed by the advancing Germans.

Although hundreds of thousands of British and French soldiers were evacuated to England, the British Expeditionary Force lost more than 60,000 men in the battle and evacuation of Dunkirk, as well as huge amounts of equipment including 700 tanks and thousands of heavy artillery guns

From May 27 to June 4, around 338,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force along with French and Belgian troops were shipped across the English Channel on a makeshift flotilla of hundreds of boats including warships but also fishing vessels, life boats and pleasure ships. Such an evacuation was made possible by a courageous rearguard action by French soldiers to delay the German advance to the beachhead. That British troops were rescued before their French counterparts was a source of some resentment among the French but Churchill, who had feared the worst, hailed a “miracle”. Although he did warn that “wars are not won by evacuations”, the events of Dunkirk allowed the new war leader to make his famous “We shall fight on the beaches” speech, which is still referred to by Britons today as a great rallying call for unity.

The Blitz and the Battle of Britain

“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” These words remain one of Winston Churchill’s most celebrated soundbites and refer to the battle in the skies between the RAF and the Luftwaffe between July and October 1940. At this stage in the war, after the occupation of France and before the entry of the USSR, Britain was alone in fighting Hitler. The “many” to whom Churchill refers were therefore those all over the world who stood against Nazism. The “few” were the Allied fighter pilots in their Hurricanes and Spitfires, aided from the ground by radar and communications superior to those at the Luftwaffe’s disposal. Crucially, the German fighters and bombers failed to neutralize these capabilities and Hitler’s plan to invade Britain, codenamed Operation Sea Lion, was abandoned.

The Supermarine Spitfire (left) and Hawker Hurricane (right) helped win the Battle of Britain and beat off Hitler’s invasion of Great Britain

However the heavy bombing of British towns and cities – known as The Blitz (Sept 1940-May 1941) continued. Hitler hoped to terrorise the civilian population into demanding a negotiating peace from its government. But despite the death of more than 40,000 people and the destruction of homes, factories and architectural landmarks, the bombing campaign had the opposite effect: practical solutions such as black-outs, improvised air-raid shelters and the evacuation of children from towns and cities, helped by Churchill’s power of motivational oratory, helped British morale and resolve stand firm and perhaps even strengthen. Even today the “spirit of the Blitz” remains for Britons a symbol of stoicism and collective defiance in the face of adversity.

The London Underground became a network of bomb shelters during The Blitz

The D-Day landings

Operation Neptune or the D-Day landings was one of the events, along with the failure of the Wehrmacht to take Stalingrad, that changed the course of the war. By landing more than 150,000 soldiers on French soil on June 6, 1944 (by the end of July that figure would rise to 1.5 million), the Allies succeeded in creating a second front for the Germans. Having to share his army between fighting the Russians in the east and the Western allies in France ultimately proved too much for Hitler. The psychological impact was also significant: it put the Allies on the front foot and, as liberators, the balance of morale – both among soldiers and civilian populations back home – swung firmly away from Nazi Germany.

Photo: Troops land on Sword Beach on June 6, 1944.

The largest ever seaborne invasion in military history required meticulous planning and ingenuity. Deception strategies to bluff the German defenders included planting false intelligence of fictitious armies to suggest an attack would come through Norway or Calais. Fighting on the day of the landings claimed more than 4,000 Allied and 3,000 civilian lives on one side while up to 9,000 Germans were killed, injured or taken prisoner. By the end of July there had been more than 600,000 military victims in the Battle of Normandy. By the end of August, the Allies had re-taken Paris from the German occupiers and the end of the war in Europe was now in sight.

Photos: Allied troops and material arrive on a beach in Normandy (left); Infantry wait under enemy fire on Sword Beach, one of two beaches along with Gold Beach under British command in Operation Neptune (right).

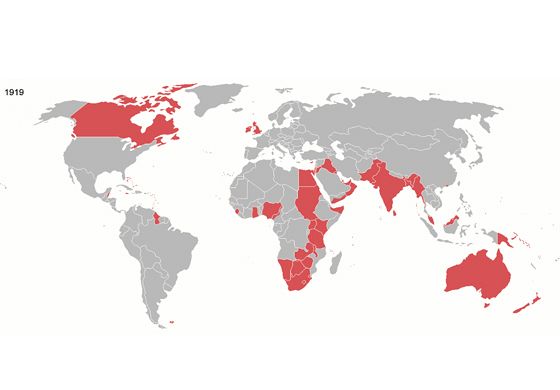

A war won, an empire lost

A price Britain paid for winning the war was losing its once-dominant empire. In terms of territory and population, the British Empire was at its largest in the years after World War One but Britain emerged from World War Two bankrupt and unable to placate growing independence movements in its dominions across the globe. In August 1942 in India, the jewel in the Imperial crown, Mahatma Gandhi gave his Quit India speech calling for passive resistance to British rule. The resulting civil disobedience movement petered out but the lust for independence proved irresistible. By the end of summer, 1947 India was an independent nation.

Graphic: The British Empire, 1919

The British army’s failure to defend Singapore, a strategically vital Southeast Asian island against the Japanese in early 1942 was another sign that British prestige was crumbling. The decolonization process took off in earnest once the war had ended and within a decade Britain had relinquished control of Palestine, modern-day Malaysia, Libya, Sudan and Ghana before what Harold Macmillan described as the “wind of change” decimated the British presence in Africa in the 1960s.

Graphic: The British Empire, 1959

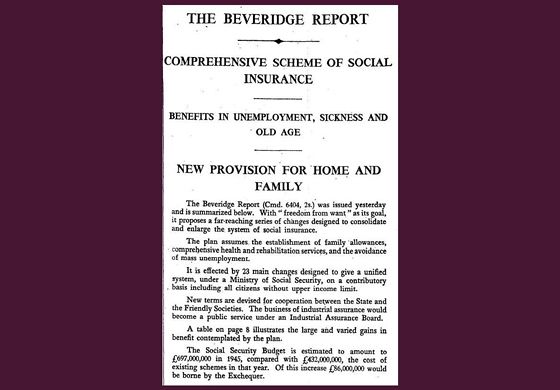

The Beveridge Report and the welfare state

One of the lasting positive legacies of World War II was the expansion of the welfare state and the promise that, after the war, life would be better for the poor, the elderly, the young and the infirm. The 1942 Beveridge Report proved to be the cornerstone of these social improvements and, led by Sir William Beveridge, it identified five ‘evils’ that needed to be fought in peace time: Squalor, Ignorance, Disease, Want and Idleness.

The report was roundly applauded among all classes of the British public. The Archbishop of Canterbury at the time referred to it as “the first time anyone had set out to embody the whole spirit of the Christian ethic in an Act of Parliament.” The Labour government of Clement Attlee beat Churchill’s Conservatives in the 1945 election and announced it would implement a “cradle to grave” welfare state based on the report’s far-reaching proposals. In the years that followed, Britain would have National Insurance, a Pensions Increase Act and a Rent Control Act and a National Health Service which meant free healthcare for all.

Also read – How WWII shaped modern Poland

Video: timeline of the end of World War II