Unreported Europe investigates the mysterious origins of the new coronavirus and asks whether we should start preparing for future pandemics.

In this episode of Unreported Europe, Jeremy Wilks investigates the mysterious origins of COVID-19 and asks whether we should start preparing for future pandemics.

Natural or engineered?

The first big question is whether this virus really is 100% natural in origin. We went to the Swiss Institute of Virology and Immunology, nestled in the rolling hills near Bern, to look for answers. The high-security lab was one of the first places in Europe to receive a live sample of the new coronavirus, officially called SARS-CoV-2, and within a few weeks they had managed to make an artificial copy of it.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Professor Christian Griot heads the facility: "Maybe it looks maybe a little bit strange in this nice environment, but yes, in here we have the SARS, the cloned SARS virus, that's right."

The clone is just as potentially deadly as the real virus, so we are not allowed to go into the laboratory. Clones are made because they are useful in developing vaccines for new viruses, and these experts used an innovative technique to make a copy of SARS-CoV-2 in just a matter of weeks.

So, one has to wonder: the fact that the Swiss made a cloned virus in record time, does that not also allow one to also draw the conclusion that perhaps the original virus was made in a laboratory like this?"

"Well there have been some speculations about that, that it's coming from the Wuhan laboratory, a laboratory which is also involved in SARS research, but I think these are just speculations and at the moment I think there's really no solid proof that this has been the case," replies Professor Griot.

World-leading virologist Professor Edward Holmes from the University of Sydney shares that view, telling Euronews: "There's nothing in the data that I have seen, in the evidence that I have seen, that says to me this is out of a lab. Again, we can't absolutely rule that out, but there's nothing that I see that suggests that."

So where does Swiss Professor Griot think the virus that causes COVID-19 come from?

"Most likely the virus came from bats, and then has been in a reservoir, or an intermediate host - the intermediate host, we don't know which animal that was - and then it was passed on to humans," he says.

Bats: suspect No 1

Bats were the source of the first SARS virus in 2002 and MERS in 2012. Now these flying mammals are suspect number one in the search for the origins of SARS-CoV-2. Bats have uniquely robust immune systems that allow them to tolerate viruses that might easily kill other animals, according to French epidemiologist Dominique Pontier, Director of the Laboratory of Excellence in Eco-evolutionary Dynamics of Infectious Diseases at University Lyon1.

"The thing that is really extraordinary is that for the majority of them (the bats), they are asymptomatic. They will not develop symptoms - I'm thinking of rabies, I’m thinking of SARS-CoV-2, I’m thinking of Ebola, Nipah, Hendra, MERS too - well, in fact it is circulating, but it seems that it doesn't cause any damage to the bats, it has no visible impact. "

Scientists believe a virus similar to SARS-CoV-2 has existed in bat populations for decades, and so the emergence of this new coronavirus probably came from sustained contact between quite different species, in one form or another.

"At some point, in the exchanges that take place, there may be the right genetic combination, both of the virus and for the human species, and at that point the transmission takes place. The emergence doesn't just happen just like that, in a click of the fingers. It's a long process, and usually the cause is the human race," explains Pontier.

Professor Holmes picks up the story: "What we do know is that there are lots of related coronaviruses that are found in bats, and the more we sample bats, the more we find that they carry coronaviruses."

"We also know that these coronaviruses, including those in bats, they jump species all the time. It's a thing that coronaviruses can do almost better than any other virus, they can jump and spread in new host species," he tells Euronews.

The pangolin connection

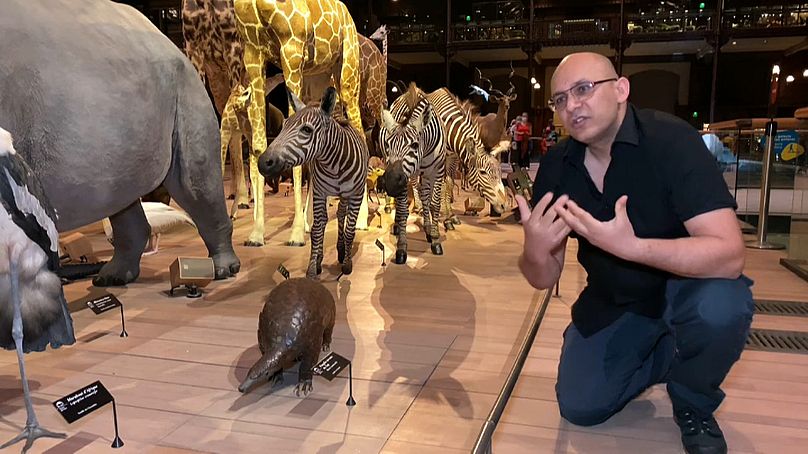

At the Museum of Natural History in Paris Alexandre Hassanin, an evolutionary virologist, is working to understand exactly that process of transmission - the role of humans and other animals in the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

Some genes in the new virus link it to pangolins - an illegally trafficked animal used in Chinese medicine.

"The question is how did these pangolins manage to catch this virus - that's the real question. Keeping in mind that these viruses have only been identified in captive animals, seized by Chinese customs, and for the moment no virus (like this) has been identified in pangolins in the wild," Hassanin says.

Professor Holmes highlights the tricky task ahead for those seeking the origins of SARS-CoV-2: "At the moment we have a kind of gap, we have bat viruses that are close, pangolin viruses that are bit close, and then the human one. But there's a kind of evolutionary gap there, between those viruses and the human one, and what happened in that gap, we still don't know."

There has been a lot of speculation about the way in which pangolins smuggled from south-east Asia may have been infected by bats in a Chinese market. However, the reality is far from straightforward. The virus found in pangolins is only a 90 percent match to the human one - getting to a 100 percent match would require about 50 years of evolutionary change. So, the mystery deepens.

"What we are looking for now is a virus that is very close to the human virus in a wild animal. What is weird, once again, is that everything converges towards Southeast Asia, and the extreme south of China, not Wuhan,'' says Hassanin, adding: "...clearly the role of the traffic of live animals looks pretty clear to me - then either it came from a live animal sold in a market, or at least kept in captivity, or it passed through a laboratory. But in any case, the origin is really the traffic of live animals. "

Tracing origin of SARS-CoV-2 will only come through detailed fieldwork, says Professor Holmes: "The key to this will looking for other animal species, and other bats, around Wuhan and other parts of China to see what they carry, and then that will help us to piece together this jigsaw puzzle. Without that a lot of this is really just hypothesis, and we don't really have any strong leader to go on."

"Practically every animal species is home to a coronavirus"

It may take several years to find a virus in an animal which matches SARS-CoV-2, but in the meantime, we should consider the future risks of other viruses, and begin preparing for the next pandemic.

Nobody knows animals better than veterinarians like Michel Pépin from the VetAgro Sup college near Lyon in France. He stresses that coronaviruses, often from bats, are literally everywhere:

"Practically every animal species is home to a coronavirus - we know you have them in cats, in dogs, in pigs, in cattle, in horses, in terms of what concerns us," says Pépin.

Establishing where SARS-CoV-2 came from is important, because the number of viruses leaping the species barrier - creating what are known as zoonotic diseases - has risen. Why is that? In this case in China it appears to be hunting, trafficking and selling wild animals. Professor Pépin insists several other factors could be at play.

"Climate change has an impact, but it is not necessarily the main factor in the emergence of infectious diseases. It's really all about the conditions - agricultural practices, irrigation, deforestation, contact with wildlife. Ecotourism - the fact that tourists want to get as close to nature as possible means that at some point we do come into contact with viruses which until that point were confined to the forests with wild fauna," he says.

SARS-CoV-2, then 3, then 4?

So, today we're battling SARS-CoV-2 - but within the next few decades these scientists could be investigating its future cousins - SARS-CoV-3, SARS-CoV-4, and so on. Scientists say the way to tackle emerging diseases is through testing, insisting they need to sample more viruses in more animals to build a more complete picture, and be better prepared for the next pandemic.

Back in Bern, Switzerland, Professor Griot sums up the potential threat of future pandemics.

"I think there are an awful lot of other viruses out there which all of a sudden can pop up, and then we have it also in the human population."

He adds: "70% of the emerging diseases have been jumping from animals to human beings, and an awful lot of them have shown a major impact on human beings. So, yes, some of them are really deadly viruses."

The final call to act earlier rather than later goes to Professor Holmes: "These things will happen again. It's happened many times in the evolutionary past, and given the way humans live today, and given the way we interact with the animal world, it will happen again, it absolutely will. So once we're through - in fact even before we're through this one - we need to plan for the next one, that's absolutely critical."