Taking a painkiller to cure a headache might seem quite harmless. But many of the medicines we take can have far-reaching impacts on the environment, wildlife and potentially our own health.

From the moment they are manufactured, pharmaceutical drugs can pollute our aquatic ecosystems and even our tap water.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Currently, residue levels in the water are low, but the problem is bound to get bigger as our use of medicine rises inexorably.

So, what can be done to curb the impact of these pharmaceutical residues?

One of the main sources of this pollution in urban water systems is us… or more precisely, what comes out of us.

“I think that people are not aware that the pharmaceuticals they eat, they leave the body and they go out with the wastewater and it's not cleaned,” says Elin Engdahl, senior policy officer for chemicals at the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.

Indeed, many of the medicines we take don’t end their lives in our bodies. But why?

Pharmaceuticals are made to resist. First, in their packaging, to ensure that when they get to us, they are just as effective. Then, they also need to resist in our body, so they don’t disintegrate straight after being swallowed and have time to act.

“That means they will reach the environment as a fairly persistent substance,” explains Stefan Berggren, the director of the Swedish Knowledge Centre for Pharmaceuticals in the Environment.

“It's a possibility that they're not dissolving in the environment and are being picked up by different species or different bacteria,” he adds.

Depending on the medication, between 30% to 90% of the active compounds in the pharmaceuticals we swallow are not fully absorbed by our body and end up in nature.

The situation is even worse for topical treatments, such as painkiller creams that we put on our skin. “It basically rinses off and only 5% to 6% get into your body,” explains Berggren.

Medicines flushed down the drain or the toilet also enter the water intact, contributing to that pollution.

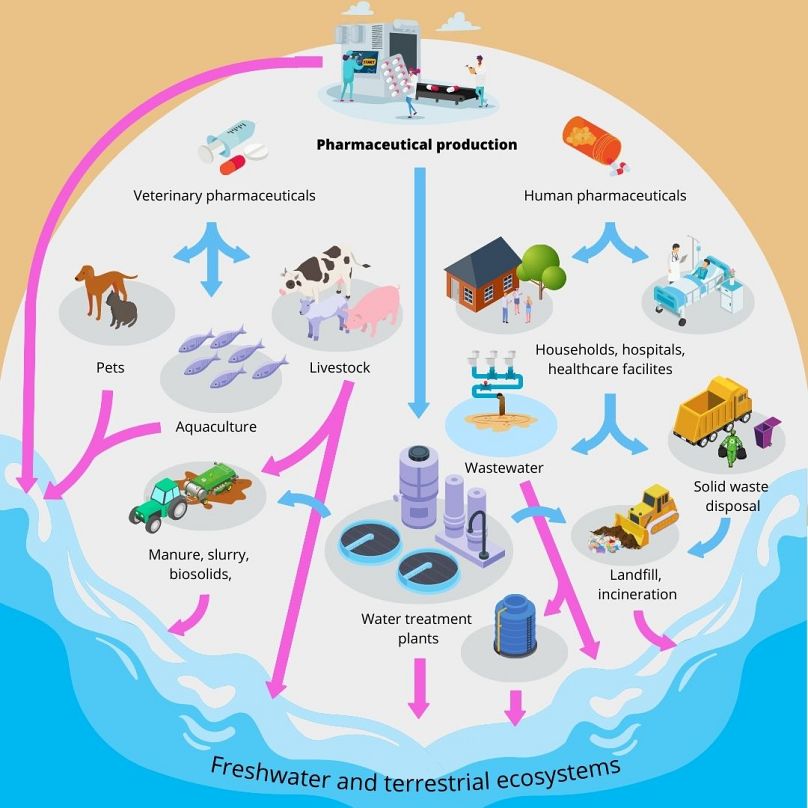

At a wider level, the water generated by hospitals and pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities also contains various pharmaceutical compounds.

These drug residues are then carried through our water systems to wastewater treatment plants.

However, the complex chemical composition of some medicines makes them difficult to eliminate through conventional treatment processes, such as activated sludge.

As of today, most wastewater treatment plants lack the capability to remove pharmaceutical residues entirely.

“The different compounds, the different substances, have different chemical and physical properties and that affects the removal efficiency,” explains Anna Maria Sundin, who works on a water treatment pilot project to find efficient solutions to remove drug residues in Sweden.

Why is this a threat to our ecosystems?

While levels of these drug residues are generally low when they come out of treatment plants, they can still be toxic to aquatic life and potentially to humans.

Studies around the world have shown pharmaceutical residues can disrupt the normal functioning of organisms, impair growth and development and interfere with reproduction and behaviour.

Some pharmaceuticals, such as hormones and antidepressants, can have particularly profound effects on aquatic organisms. This can lead to population decline and disrupt the natural balance of ecosystems.

Oral contraceptives, for instance, have caused the feminisation of fish and amphibians, which is when males grow female egg cells and reproductive ducts in their testes.

This “intersex” mutation can compromise their reproductive capacity which can have consequences for population levels.

“If the fish can't reproduce, they will sort of die off and then we won't have any fish. And that will affect biodiversity as a whole,” says Engdahl.

Are there pharmaceutical residues in tap water?

But it’s not only ecosystems that are impacted. “We also have these pharmaceuticals in our drinking water, especially if we take the water from surface water,” explains Engdahl.

“Since the surface water is really polluted, we have a huge cocktail of pharmaceuticals,” she adds.

A study from 2016, detected more than 100 different pharmaceutical substances in the aquatic environments of several European countries. In Germany and Spain, more than 30 different pharmaceuticals were detected in tap water.

While the direct health effects on humans are not yet fully understood and more research is needed, prolonged exposure to even low levels of pharmaceuticals through drinking water consumption raises concerns.

Engdahl warns that children could be most at risk.

“If you affect the hormonal system, for example, in a developing child, that can affect the reproductive organs. It can also affect brain development,” she explains.

How is this contributing to antibiotic resistance?

It’s difficult to determine the actual levels of contamination, whether in the environment or in our water systems, as many wastewater plants are not equipped for their detection.

However, despite the lack of accurate monitoring and long-term studies, this type of pollution is bound to get worse.

‘We need to clean the wastewater because we need the pharmaceuticals, so we're not going to stop using pharmaceuticals,” says Engdahl.

Pharmaceutical consumption has been increasing for decades, driven by a growing need for drugs to treat age-related and chronic diseases, and by changes in clinical practice.

Meanwhile, the use of antibiotics in farming is set to increase by 8% between 2020 and 2030, according to a new study published earlier this year.

This is particularly worrying as it is a major contributor to antimicrobial resistance.

When antibiotics, along with other medicines administered to animals, end up in manure or are released through runoff from agricultural fields, there is a risk that they will seep into the ground and contaminate the water.

Once in the water, bacteria with prolonged exposure to antibiotics can become resistant.

The environment then acts as a reservoir for these resistant organisms where they can develop and spread.

The European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) estimates that 33,000 people die in Europe each year as a direct result of antibiotic resistance.

However, this is not only caused by bacteria in water. Antimicrobial resistance occurs naturally over time, usually through genetic changes. These resistant organisms can be found in people, animals, food, plants and the environment (in water, soil and air).

Cleaning wastewater will not solve the problem entirely and many experts stress the need to tackle the problem before it reaches the environment.

“Antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest healthcare problems that we will face,” Engdahl says.

“When antibiotics don't work anymore, there will be a lot of human deaths. So, we need to stop releasing antibiotics into the environment,” she adds.

So… what are the solutions?

Enhanced wastewater treatment

Advanced wastewater treatment technologies, like those tested at the Uppsala plant where Sundin works, are being developed and explored.

These include additional filtration steps such as activated carbon filtration. In this case, the contaminants are attracted to and absorbed into the surface of the carbon particles. Combined with ozonation, an advanced oxidation process using ozone, it can effectively remove most pharmaceutical compounds.

At the European level, the European Commission has proposed that any major wastewater treatment plants - those that collect water for more than 100,000 people or release in sensitive areas - install a fourth cleaning step to clean these pharmaceuticals.

This is called a quaternary treatment which targets emerging pollutants such as antibiotics, pesticides, hormones, illicit drugs and microplastics.

However, simply treating the water might not be enough.

Tackling the problem at the root

“You have to work on the whole sort of life cycle of the pharmaceutical,” says Berggren.

“You need to work on both developing green pharmaceuticals from the start [...], on more eco-friendly prescriptions. You also need to work on the wastewater treatment plants [and] on the collection,” says Berggren.

As individuals, we can contribute to reducing the environmental impact of medicines by using them responsibly and respecting dosage and treatment plans.

Over-prescription, self-medication using over-the-counter drugs and misdiagnosis of symptoms can increase the amount of pharmaceuticals in the environment.

It’s also key that healthcare professionals and veterinarians reduce the use of antibiotics in farming.

Similarly, farmers need to implement safe practices when storing and using manure and slurry from livestock treated with pharmaceuticals.

Healthcare professionals and pharmacists can also play a significant role in educating patients about the proper use, storage, and disposal of medicines.

The pharmaceutical industry can also help to reduce residue levels by developing greener medicines and production processes.

But tackling pharmaceutical pollution requires more than just isolated solutions. Healthcare providers, individuals, pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies will need to work together to promote responsible medication use, improve manufacturing practices, enhance wastewater treatment, and foster the development of eco-friendly pharmaceuticals.