What connects aquaculture students in Spanish estuaries to EU policymakers in Brussels? A continent-wide network monitoring ocean conditions in real time, shaping fisheries policy and driving sustainable investment in Europe's blue economy.

In the Galician estuaries of northwest Spain, countless rafts dot the water surface. Each one is a platform for growing mussels and other shellfish. For students at IGAFA, one of Spain's leading aquaculture schools, these platforms serve as an outdoor classroom where future marine farmers can learn their trade.

Europe's “blue economy” — the umbrella term for all sea-based industries working towards sustainable growth — employs four to five million people across the continent. Aquaculture alone provides tens of thousands of jobs in Spain, France, Greece and Italy, creating demand for specialists who can work at sea, in laboratories, in offices and processing plants. The sector produces sustainable, local protein that eases pressure on wild fish stocks and reduces Europe's reliance on imported seafood.

Yet growth remains constrained. "There are many uncertainties," explains José Ventura, director of IGAFA. "You don't know how the market will fluctuate. Another is environmental uncertainties. We face constant climate change that affects local production, especially operations like these that depend directly on natural environmental conditions."

Sensors beneath the surface

Even basic water characteristics like salinity can change unpredictably. In Galicia's estuaries, where ocean saltwater mixes with river freshwater, tides and rainfall cause salt levels to vary dramatically. Sometimes they reach levels that threaten shellfish survival.

This is where technology can help. Galician estuaries are continuously monitored through a network of automatic platforms operated by INTECMAR — the Technological Institute for the Control of the Marine Environment of Galicia. The underwater sensors need only occasional cleaning to remove algae. Otherwise they work autonomously, powered by solar and wind energy, transmitting constant readings of temperature, salinity, pH and oxygen levels.

"Having that data in real time certainly makes resource management easier," says Silvia Allen-Perkins, a technician at INTECMAR. "Anyone can conveniently access it through our website and track how it evolves."

Automated monitoring represents just one data source of many. Researchers also visit industrial aquaculture facilities to collect water and shellfish samples for laboratory analysis. This detailed knowledge of coastal water conditions — physical, chemical, biological — is essential for producers optimising their operations and guaranteeing seafood safety.

From local waters to European databases

The information doesn't stop at regional research institutes. It flows into vast international databases. "These data from this small region join the rest of the European data," says Pedro Montero, head of INTECMAR's oceanography unit. "Together they give a much broader view of the marine world."

In Vigo, Galicia's largest city and a major hub of Europe's blue economy, CETMAR channels this data into regional and EU-level decision-making. "If we want fair policies for our blue economy sectors in Europe, we need to have the best data," explains Rosa Chapela, the institute's managing director. That includes information on maritime spatial planning, port activities, sand extraction and military operations in maritime zones.

JRC: where policy meets science

The data journey continues east to Ispra, a lakeside Italian town that houses the European Commission's Joint Research Centre. Here, Jann Martinsohn leads the Ocean and Water Unit, which analyses information from Europe's fishery and aquaculture sectors, Eurostat, EU agencies, member states and countless other sources. The findings are published annually in the EU Blue Economy Report — a clear, easy to use document that informs policy and guides billions in investment.

"One striking example is obviously the common fisheries policy," says Martinsohn. "The Commission even has the obligation to take up the information we produce." The data also feeds into the Zero Pollution Action Plan and helps shape investment opportunities across the sustainable blue economy.

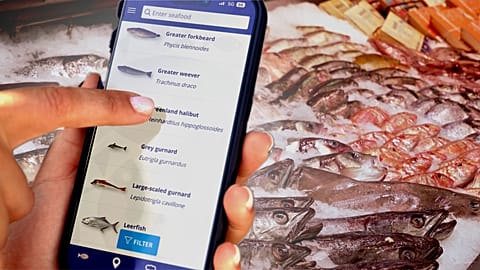

All this research becomes publicly accessible through the EU Blue Economy Observatory that maintains a free online resource offering charts, maps and current data. "Stakeholders — be it policymakers, be it entrepreneurs — can see what is going on in the blue economy sectors," Martinsohn explains. Interactive dashboards allow users to analyse trends in maritime transport, fisheries, energy and the ongoing energy transition.

Connecting citizens to the sea

Back in Vigo, the blue economy's connection to everyday life takes a visible — and walkable — form. The port, once a barrier between the city and the sea, now features a "blue path" — a seven-kilometre walkway that opens port areas to citizens and tourists. Industrial history, marine wildlife and cultural heritage are on display, through public information panels and a tailor-made mobile app.

"It's essential that ports take responsibility for making citizens aware of the wealth and biodiversity of the estuary," says Gerardo González Alvarez, who heads the port's blue economy department.

The path ends at a future underwater observatory, where visitors will be able to descend beneath the surface, surrounded by artificial reefs teeming with marine life. The message is clear: economic growth, jobs and innovation matter. But the ocean remains a living system that sustains human life — and that human activity must sustain in return.