Just an hour away from Warsaw, along the River Bug, stands a wooden house, hiding layers of history, complexity and architectural innovation. The creation and residence of renowned Polish architects Oskar and Sofia Hansen is both a showcase and a moving tribute to the "Open Form" style.

Taking your first steps towards the Hansen House, the first thing that meets the eye is an unusual wall. Rather than an airtight barrier, it is permeable, interacting with the surrounding environment, and allowing the outdoors in. A triangular roof, connecting the garden with the house, has a similar message: the dwelling and its environment combine to make a larger, greater whole.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The idea? "Open Form" architecture, a movement pioneered in the 1950s by the Hansens and embodied in their own living space. As the name suggests, the style emphasizes blurred boundaries, a user-centric focus, and a break with the modernist orthodoxy promoted by Le Corbusier.

"We see different shots of greenery through the gaps, specially designed windows, which form the framework of this space. Oskar Hansen said that Open Form is a frame of reference for looking at the world," Tomasz Fudala, curator of the Hansen House tells Euronews.

A poetic idea

The experimental Hansen House is an outstanding example of architecture included in the Iconic Houses Network list, to which people from all over the world, including Switzerland, Brazil and the University of Venice, travel to every year. It inspires wonder and awards architectural innovation.

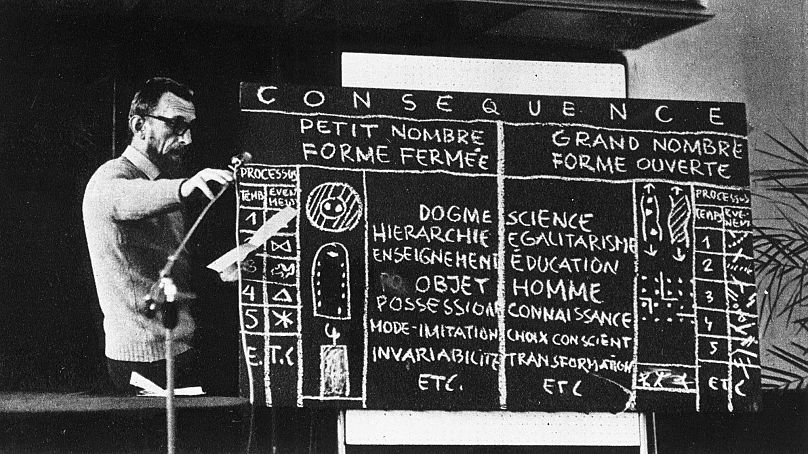

Oskar Hansen applied his concept of the open form in visual games he played with students while he taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw throughout the 1950s. They focused on emphasizing the difference between an open and a closed form, principles which were crucial in all areas of his life: from his architectural work and his home to his personal life and moral convictions.

"Open form was that good, proper architecture that provides a background for life, does not dominate us, is humanistic. And the closed form? It's easiest to imagine such a static, ancient statue on a pedestal, something centralising, gaining power over us. And then Hansen developed this, he said that the open form is ecology. That is the understanding of nature and our place in it. And the closed form is war, destruction. So it was quite a poetic and general theory, but he actually implemented it throughout his life in the form of various games. But also in his own home," Tomasz Fudala explains.

Architecture without a budget

Everything in the Hansens' home was created by the independent work of its inhabitants, who took the passion they felt for their work into their personal living space. As the curator of their home tells Euronews, this place is particularly interesting because it shows that you don't need a lot of money to build. The house was built from recycled materials, demolition materials and found boards, again showcasing the innovative nature of the movement Oskar Hansen espoused.

"The greatest works of architecture can be created from found wood. From recycled materials. From poor materials. In fact, here the builders had no budget. And it's a shock for many people who come here, but such a positive one, because they think: wow, that means you can design, draw yourself something, build something, but it's not all based on big money, so it's great," says Tomasz Fudala.

"Here the Hansens show us that you can make an outstanding work of art actually very cheaply, with the power of imagination, creativity, and, well, great talent," he adds.

Zofia and Oskar Hansen

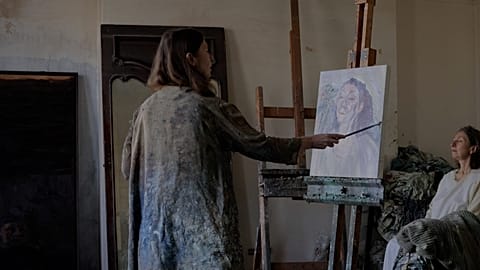

Zofia Hansen, Oskar's wife, was also an architect. Her distinctive mark is also felt throughout the walls of the couple's home. Their relationship was one of collaboration and building upon the ideas of the other. The two met in 1950 while studying architecture in Warsaw.

"Zofia Hansen worked in the circle of the Warsaw Housing Cooperative, that is, the circle of modernists, architects who were interested in ensuring that housing estates were humanely built, that there was greenery, that children could play freely and that cars did not invade them," Fudala explains.

"He, in turn, had such an opportunity to go to France after the war and met Pablo Picasso there. He met and worked with Pierre Jeanneret, which is Le Corbusier's cousin. He had the opportunity to see what the West looked like at the time when the new system, the Polish People's Republic, real socialism, was being installed in Poland," says the curator.

Blurring the boundary

We meet Wanda Chróścicka, a neighbour of the Hansens for 40 years, in Szumin, the village about an hour away from Warsaw where the couple lived. She recounts tales of Oskar Hansen's sense of humour, and visits she made to the house for tea and chats with the couple.

She sits down on a bench in front of their house, a bench placed there on purpose to harken back to older Polish habits of welcoming guests. The space is remarkably modern, but doesn't fail to take inspiration from the past.

"Here, there has always been a bench of some kind, because the farmers used this road to go and cultivate the fields, and it was usually here that they stopped, chatted, reported to each other, told jokes, on their way back after work. Just like people. Mr. Oskar Hansen decided that the bench could not be abolished. He built a bench, which would continue to serve a similar role, but not only. It worked out nicely, because people who stopped by would talk, and inside the Hansens would sit at a table on the terrace, listening to one another. Hansen could hear what the farmers were talking about. The farmers heard what the Hansens were discussing," Wanda explains.

In this way, the Open Form movement meant that the couple opened up their lives to the surrounding community, blurring personal boundaries as well as architectural ones.

The house in Szumin began to be built between 1968 and 1970 and was never actually completed. The Hansens created it continuously, in collaboration with the village community, with their friends, and with their children.

Wanda gets up from her bench and invites us inside. She points out to us how colorfully the wall is constructed, the one that first catches the eye.

"From the outside it was grey with a white stripe, here [inside] it is an absolute negative - it is white with a grey stripe. This is an indication that we are already inside," she explains.

Living house and working at night

Wanda Chróścicka takes us on a tour of the Hansen space room by room. Throughout the property, there are quite a few elements that are practical in use and at the same time act as teaching apparatuses. For example, a table that extends through the interior to the exterior. All its planks are two-coloured and can be arranged as desired.

"Once, when I came to them for tea, Mr Oskar suggested that I arrange the colours on the table in such a way as to make it nice and pleasant for me. Another time he asked me to express the mood I was in today with this. So these were quite difficult games. But very interesting", recalls Wanda.

The space was made to be interacted and played with, by the Hansens themselves, as well as by the surrounding community.

For the Hansens, colours always played an important role. "Above all this white that appears at various points. It had an guiding role, telling people which way to go and so on," the neighbor explains.

We go up to the first floor with her to see Oskar Hansen's studio. It's a wonderful, bright, spacious room with a panoramic window.

"Oskar spent his days either in the orchard, tending to his pigeons, or in the garage. On the other hand, in the evening the light would come on and he would stay here until dawn. So I think he did all his creative work, his designs and other things at night," Wanda says with a smile.

Now the room is quite empty, but as a neighbor of the family reveals to us, there were once bookshelves filled to the brim in the studio.

Birds, cars, and wine

Wanda leads us back downstairs. She shows us the toilet with its glass ceiling. Apparently Sophie Hansen liked this place in autumn because the leaves covered it from above.

Next to it we see another studio where Oskar Hansen made furniture, as well as his aviary and the garage where he kept his beloved car, of which only the license plate remains.

We look at the garden. Chróścicka recalls that the crop of this small orchard was Hansen's homemade wine. It was not good, but no one ever told the landlord that.

"I don't know if you know, but all these old trees, they were all planted by the Hansens and each of these trees has a name. Here somewhere grows Igor, Alvar, I don't know exactly which one. And on the other side there's a linden tree called Zofia and an oak called Oskar," she says, pointing along the property.

Not an open-air museum

The Hansen House is owned by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, which wants to keep it in the spirit of Open Form, i.e. meaning that it will continue to remain fluid, never stagnant or declared "complete". Breaking with tradition, it is meant to be an experimental space flowing with life.

"This is not intended to serve as an open-air museum, but rather showcase the house through various activities. Workshops are held there, various meeting, students come on trips, and the house remains alive. It is a museum, where you can actually enter the real toilet of its owners, see how they ate, see their personal objects, but also perform the games they did, while doing some kind of artistic or architectural task," says the curator of the Hansen House.

"The Hansens' son, Igor Hansen, said he wanted viewers to "live" in the house for a little while, to feel comfortable there. To sit down, take a close look at everything and sort of blend into this whole situation that his parents had designed," Fudala adds.