Everyone is talking about 'nepo babies'. How do the children of famous people feel about it, and can working class people still make it in the arts?

Hollywood was built on dynasties - from the Warner Brothers and the Barrymores to the Fondas and the Coppolas.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

So it shouldn’t be a surprise then, when you watch a movie or TV show, that you often see familiar surnames in the credits, or find yourself wondering “Where have I seen this face before?”

But for some reason, more than ever before, the idea of famous people’s children working in the same industry as their parents has become an obsession for us commoners. Blame the internet.

Earlier this month, New York magazine seized on our collective curiosity with what they called “An all but definitive guide to the Hollywood nepo-verse”.

On its cover, the biweekly magazine declared 2022 the year of the “nepo baby” (short for nepotism baby), publishing an extremely thorough deep-dive into the world of celebrity children.

The series of articles and infographics revealed that, more likely than not, your Hollywood faves are probably the product of nepotism.

These “nepo babies” are starring in movies, putting out music, selling everything from shampoo to candles to candy. And sometimes, like in the case of Brooklyn Beckham, they’re trying everything all at once – the son of David and Victoria Beckham has been a photographer, a bartender, a model and a chef.

(Let’s take this opportunity to resurface his photography book about elephants in Kenya, which has been prime meme material for years.)

Some European nepo babies include French entertainment royalty Charlotte Gainsbourg, daughter of singer Serge Gainsbourg and actor/singer Jane Birkin; Swedish actor Alexander Skarsgård, son of actors Stellan and My Skarsgård; and Italian model/actress Deva Cassel, daughter of actors Vincent Cassel and Monica Bellucci.

Nepo babies respond

While the idea of nepo babies isn’t new, the New York series set the internet ablaze with memes and hot-takes. The response was so prolific that some of said nepo babies felt the need to come forward and defend themselves.

Jamie Lee Curtis, the daughter of actors Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, who called herself an “OG nepo baby”, said the recent discourse was “just designed to try to diminish and denigrate and hurt”.

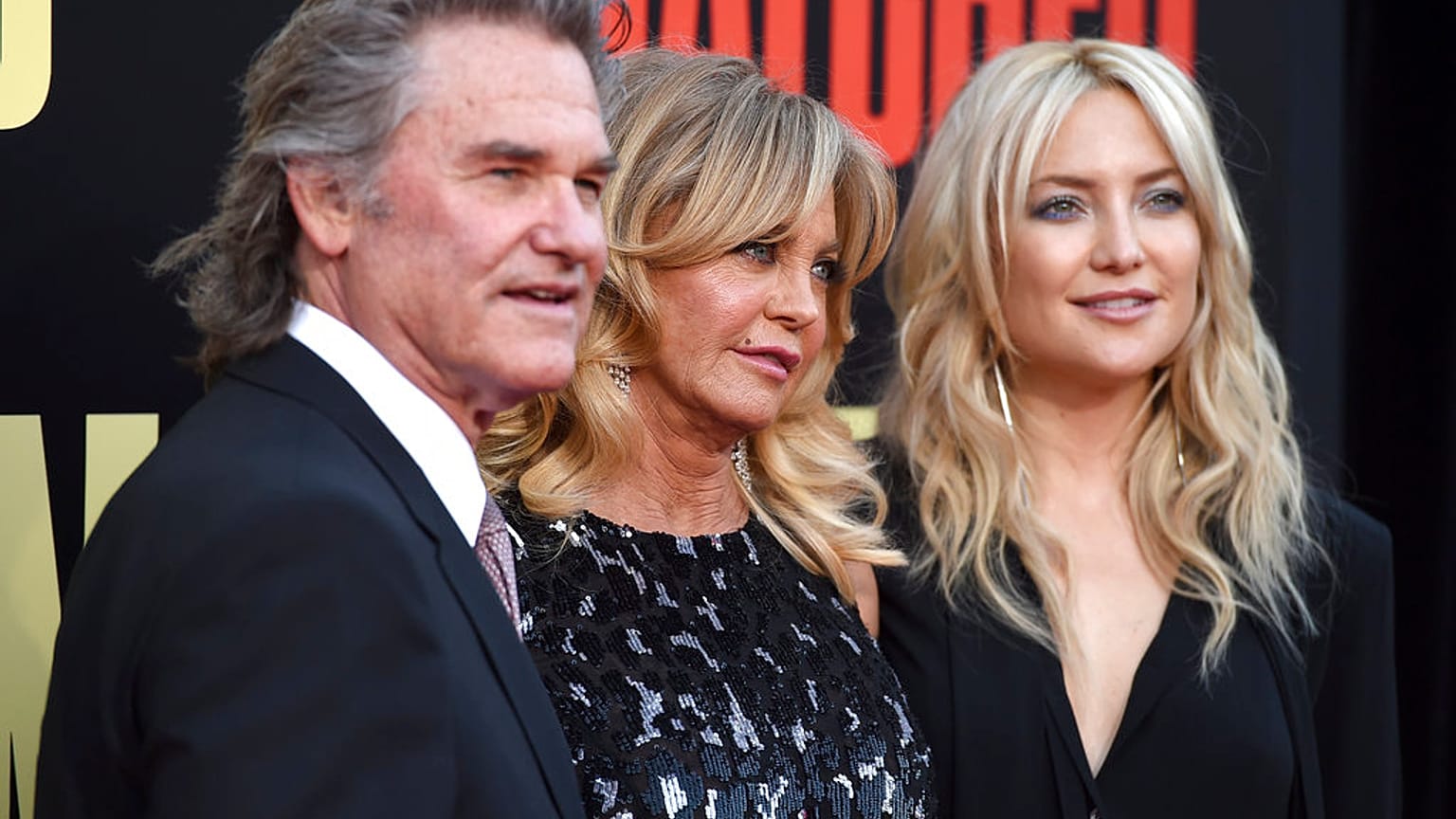

Kate Hudson, daughter of actors Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell, told The Independent that she thinks nepotism is more prevalent in other industries, and that talent trumps parentage.

“I don’t care where you come from, or what your relationship to the business is – if you work hard and you kill it, it doesn’t matter,” she said.

Musician and actor Lily Allen, the daughter of Trainspotting actor Keith Allen and film producer Alison Owen, ironically referred to herself as “chief nepo baby defender” after tweeting that people should really be worried about nepotism in legal firms, banks and politics “if we’re talking about real world consequences and robbing people of opportunity.”

Eve Hewson, Bono’s kid, pointed out that even the CEO of New York magazine is a nepo baby.

A lack of diversity in the arts

The discourse did at times tread into deeper waters as people discussed how more than who your parents are, how much money they make or what socio-economic class you grew up in often determines your success in any industry, but especially the arts.

New research from the UK showed that the percentage of artists (including musicians, actors and writers) who come from working class backgrounds shrunk by half since the 1970s.

Just 7.9 per cent of the youngest creatives come from working class families.

The study, published by the British Sociological Association, says that while it may look like it’s getting harder for working-class folks to make it in the arts, the numbers reflect Britain’s shrinking working class on a societal level.

“The chances of getting into creative work are profoundly unequal in class terms, but they are neither more nor less unequal than they ever have been. As across the rest of the economy, there was no ‘golden age’ of classless access to creative employment.”

Initiatives to get more working class people in the arts have been gaining ground on both sides of the Atlantic in recent years.

In a bold and widely criticised move, the British government announced earlier this year that it would transfer cultural funding for the next three years to support organisations in regional centres rather than around the capital.

And in November, voters in the US state of California - home to Hollywood - overwhelmingly voted to inject an additional $1 billion (€941,050,000) into public arts education across the state, especially in poor neighbourhoods.