London's police demanded Instagram remove Chinx (OS)'s song. The company's oversight board has uncovered a trend in Meta listening to the police without question.

Meta’s Oversight Board has said the company shouldn’t bow to police pressure to remove drill music.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Drill, a genre of rap music, is a regular feature in the British press for its references to UK gang culture. The board’s advice comes after Meta removed a drill song at the request of London’s Metropolitan Police service.

Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, cooperated with London’s police force when they emailed a request to Meta’s escalation team to take down Chinx (OS)’s song and video for ‘Secrets Not Safe’ from Instagram in January.

Chinx (OS) allegedly referred to a 2017 shooting and included a “threat to action”, which Meta found broke their safety rules.

But the oversight board has questioned the consistency of the decision making to remove the song.

When Chinx (OS) appealed the ban, a reviewer outside Meta’s escalation team reinstated the song. It was taken down again after the police reiterated their request.

Should Meta listen to the police?

The oversight board has questioned whether Meta is acting independently with the advice of the police, or merely kowtowing to their requests.

In the case of ‘Secrets Not Safe,’ the board found that Meta’s review didn’t find strong evidence that the song contained a credible threat. Lacking the evidence, “Meta should have given more weight to the content’s artistic nature,” the board wrote.

“While law enforcement can sometimes provide context and expertise, not every piece of content that law enforcement would prefer to have taken down should be taken down.”

The board has also criticised the lack of clarity for the way the police raise issues with content on their platforms.

“The channels through which law enforcement makes requests to Meta are haphazard and opaque. Law enforcement agencies are not asked to meet minimum criteria to justify their requests, and interactions therefore lack consistency.”

It found that all 286 requests the Metropolitan Police made to remove content in the period of a year involved drill music. As drill is a genre popular with young Black British men, this singular focus raises clear issues regarding racism and profiling.

Of the 286 requests, 255 saw the company remove content.

The board has also questioned how controversial material decided over “at escalation” shouldn’t be beyond appeal from content uploaders as it currently is.

As a result, the oversight board has overturned Meta’s decision to remove the song.

It has also recommended that Meta creates a standardised and transparent system for removing content, where complainants need to clearly state which policy it violates. It must also review and publish data on removal requests.

Removing rap lyrics from courts

The decision echoes a recent open letter signed by multiple musicians demanding rap lyrics are not admissible as evidence against artists in US courts.

“Rappers are storytellers, creating entire worlds populated with complex characters who can play both hero and villain,” the statement read. “But more than any other art form, rap lyrics are essentially being used as confessions in an attempt to criminalise Black creativity and artistry.”

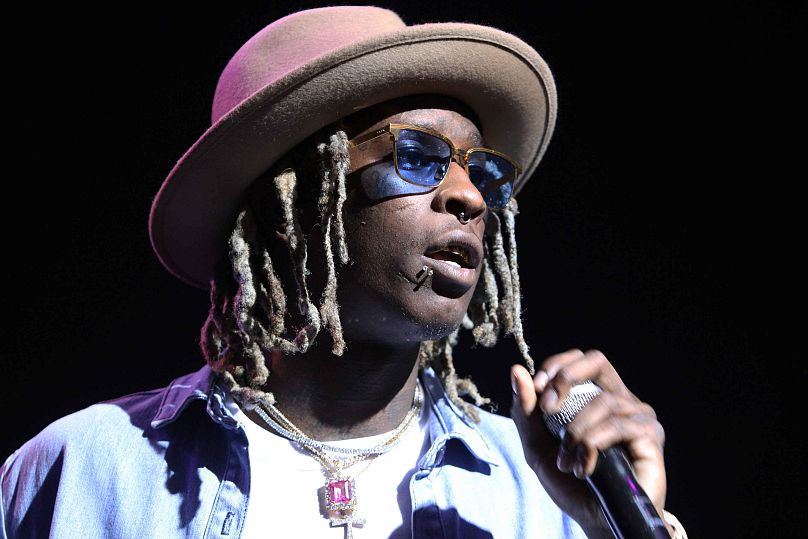

‘Art on Trial: Protect Black Art’ was signed by Megan Thee Stallion, Alicia Keys, Drake, 21 Savage and Coldplay among others. It was created in response to a criminal case against the rapper Young Thug where the prosecution cited his lyrics.

In the UK, rappers have had similar treatment. British drill rapper Unknown T, real name Daniel Lena, had his lyrics attempted to be used as evidence against him in a murder trial.

The judge blocked it on that occasion, but when Digga D, real name Rhys Herbert, was found guilty of conspiracy to commit violent disorder after a trial that included his lyrics as evidence, he was given a year in prison and forced to provide his lyrics to the police 24 hours before releasing any new music.