Which films is Godard most famous for and which are must-sees?

Jean-Luc Godard, one of the most famous director to emerge from French New Wave, has died at the age of 91.

The director of A Bout de Souffle (Breathless), Une Femme est une Femme (A Woman is a Woman) and Le Mépris (Contempt) was described by many as a revolutionary auteur, his style and cinematic approach being at the heart of the Nouvelle Vague movement that purported to rewrite the language of cinema in the late 50s and 60s.

He is remembered for a rich body of films and his most famous quotes: “Photography is truth. The cinema is truth 24 times per second” and “You don't make a movie, the movie makes you.”

What was the French New Wave?

The post-war European cinema scene saw a young generation of directors reacting against the cinematic conventions, in both content and form. This was the foundation of the Nouvelle Vague.

In 1950, Godard joined the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin, where he met Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut, future influential members of the movement. He initially approached cinema through criticism, writing for the Cahiers du Cinéma, founded by critic and theorist André Bazin, before forming a collective and starting to experiment with short films.

Over the following years, Godard produced a series of shorts and privileged the use of natural lighting, long takes, improvised dialogue, all while toying with the established rules of editing and narrative continuity. Unwavering radicalism was the key for Godard.

Jacques Rivette, Chabrol and Truffaut were some of the first directors to experiment with style, but Godard was the one who gained notoriety and international success with his debut film, 1960's A Bout de Souffle (Breathless). The film starred Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo and it was the start of his most successful filmmaking years.

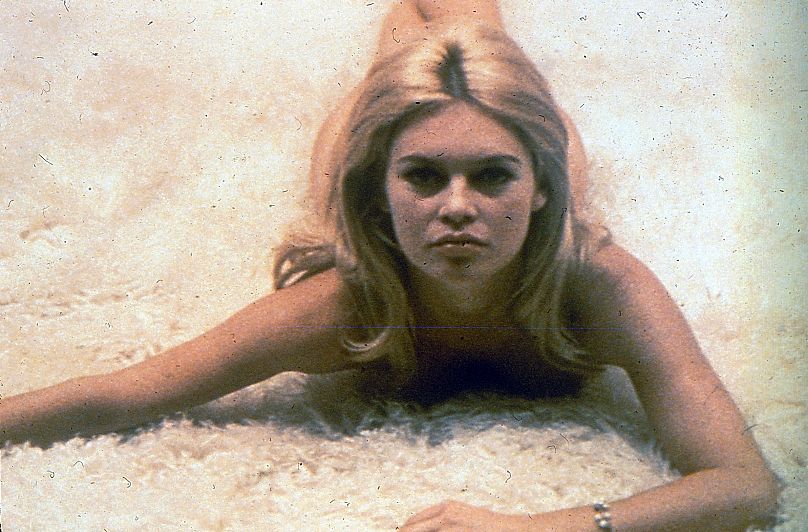

His most commercially successful film was 1963’s Le Mépris (Contempt), starring Brigitte Bardot, followed by Pierrot le Fou (1965), his second film starring Jean-Paul Belmondo.

His final film in the Nouvelle Vague genre, 1967’s Week End, was an attack against the bourgeoisie and consumerism, and featured the closing credits "La Fin du Cinéma" ("The End of Cinema”).

Hugely inspired by the May '68 protest movements in France, Godard became politically outspoken – his revolutionary and Marxist rhetoric began to bleed even more into his films – and he even led protests that shut down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, to show solidarity with the students and workers.

He then fell out of fashion in the late 70s and 80s but did enjoy comeback in 2001 for his film Eloge de l'Amour (In Praise of Love). Since then, his experimental features Film Socialisme (2010) and Adieu au Language (Goodbye To Language) (2014) proved to be too challenging or borderline unwatchable for some. Film Socialisme in particular is a baffling montage of images and sounds that share no apparent link.

Still, his contribution to cinema was recognised with a 2010 honorary Oscar – for which the citation read: “For passion. For confrontation. For a new kind of cinema.” – and Goodbye To Language saw him win the Jury Prize at Cannes. His last film, a so-called avant-garde essay titled Le Livre d'Image (Image Book), which was selected for the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, was awarded a one-off “special Palme d’Or”.

Which Godard films should I watch?

Many saw Godard as a titan, so much so that his oeuvre seems impenetrable and the man something of an enigma: iconic genius to some, pretentious refusenik to others, who saw a filmmaker progressively drunk on his own mythmaking and his bold statements about cinema being dead.

However you may feel about him, its undeniable that the period between 1960 and 1967 was his most productive, important and influential.

Here are the three films from this period you should make time for.

A Bout de Souffle (Breathless) (1960)

Starring Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo, this story of a car-thief who shoots a policeman and goes into hiding in Paris saw Godard use hand-held cameras, monologues to camera without a real script (Godard would often call out actor’s lines to them from behind the camera), natural light, little-to-no makeup for the actors and then-disorientating jump-cuts. It was an unorthodox deconstruction of narrative and continuity conventions that was rich in intertextuality and broke all the rules. This French film noir embodies the Nouvelle Vague by capturing the spirit of freedom in post-war Paris, and after just one film, he had established himself as one of the most important director’s of his generation.

Le Mépris (Contempt) (1963)

This was Godard’s most commercial undertaking, a big-budget film starring Brigitte Bardot. It stars Michel Piccoli as a screenwriter wrestling with the demands of his director and producer, and the disintegration of his marriage. It is the portrait of a crumbling relationship and remains to this day a visual treat, with tracking shots and the presence of red hues - a fixation for colour that would be further seen in Godard’s later films.

Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Teaming up once more with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina, the director’s then wife and muse, Pierrot le Fou is an incredibly stylish road movie that follows a man frustrated with his life and marriage and who decides to hit the road with his ex-lover. Throughout, the fourth wall is broken, the audience constantly acknowledged and the film serves as a means to better break the illusory nature of cinema. It cemented Godard as France’s “enfant terrible” of cinema and a filmmaker obsessed with the fragility of human relationships.