Education has a special obligation to be finely attuned to the risks of AI. At this moment, we must not be so dazzled by its evolutionary leaps that we are ignoring these risks, Stefania Giannini writes.

The use of generative AI in schools is being rolled out at a rapid pace, with a worrying lack of checks, rules, or regulations.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I’m convinced that these AI tools open new horizons for education, which can benefit learners and teachers.

At the same time, I am concerned that their adoption often takes place without any review, even though these tools’ capacity for bias and serious factual errors are widely acknowledged facts.

AI can be harnessed, contrary to popular suggestions

Why are the "normal" checks and balances applied to teaching materials not being applied to the use of generative AI such as ChatGPT in the classroom?

To a certain extent, generative AI is a mystery to its designers; large language AI models that are feeding AI are often described as “experimental” by their developers.

If their own creators do not yet understand why large language models hallucinate facts, then we must halt right now and pause for thought before unleashing this technology on learners.

The educational sphere is one in which a regulator should exercise control, even if, today, this is not happening in the free market.

The use of AI can be harnessed or limited, as is the case for other technologies, even though it has become popular to suggest this is somehow not feasible.

We have robust rules in many countries that control and restrict the use of technology that is known to be dangerous or is still too new to justify a wide or uncontrolled release.

While these rules may not always be perfect, they are quite effective.

We should worry about teacher-less schools and school-less education

In May, a UNESCO global survey of over 450 schools and universities found that fewer than 10% have developed institutional policies or formal guidance on the use of generative AI applications.

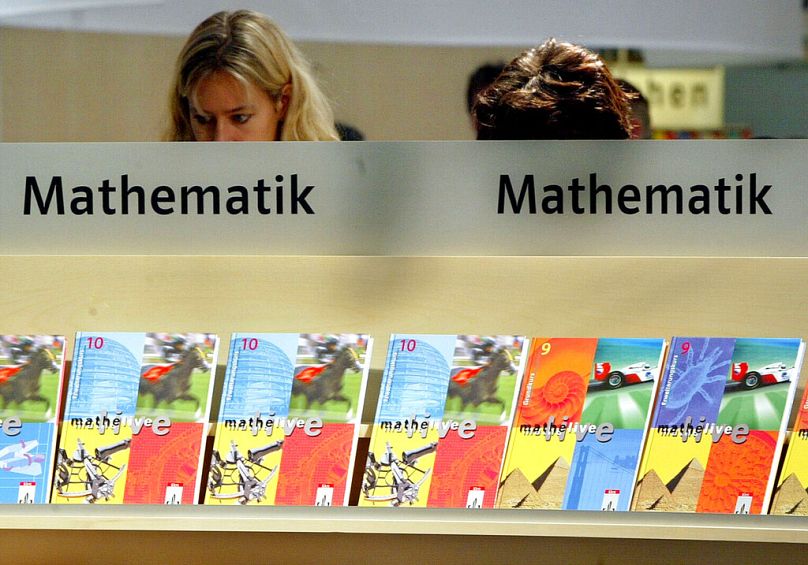

In most countries, the time, steps, and authorisations needed to validate a new textbook far surpass those required to move generative AI utilities into schools and classrooms.

Textbooks are usually evaluated for accuracy of content, age-appropriateness, relevance of pedagogy and accuracy of content.

In addition, they are assessed for cultural and social suitability, which encompasses checks to protect against bias, before being used in the classroom.

While we all see the positive impact of personalised learning pathways, whether it concerns content, teaching methodology or pedagogy, I worry that the sudden arrival of new generative AI tools could accelerate a drive towards the automation of learning: teacher-less schools and school-less education.

Instead, we should drive for the exact inverse of such a dystopian future; we must raise the status of teachers and never doubt the crucial importance of school attendance.

Access, creativity and imagination

Education is a deeply human act rooted in social interaction. As such, education should use technology to empower learners’ creativity and imagination.

It should also be used to enable teachers to facilitate access to multiple sources of information and knowledge while prioritising socio-emotional learning and skills.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when digital technology became the primary medium for education, we witnessed the suffering of many students both academically, mentally, and socially.

Investment in schools and in teachers is the only way to solve the problem that today, at the dawn of the AI Era, more than 750 million people still cannot read or write an SMS.

Evidence shows that good schools and teachers can resolve this persistent educational challenge — yet, the world continues to underfund them.

Over the course of my career, I have witnessed at least four digital revolutions: the advent and proliferation of personal computers; the expansion of the internet and search; the rise of social media; and the growing ubiquity of mobile computing and connectivity.

The internet and laptops were not immediately welcomed into schools upon their invention. We discovered productive ways to integrate them, but it was not an overnight process.

Dazzling AI evolutionary leaps should not distract us from its risks

UNESCO’s annual report on education, the Global Education Monitoring Report focusing on the use of technology in education has just been published.

The report urges countries to carefully consider the use of technology in their schools, warning that generic regulations may not be sufficient for the education sector.

To validate new and complex AI applications for formal use in schools, UNESCO is calling on ministries of education to build their capacities in coordination with other regulatory branches of government, in particular those regulating technologies.

In 2021, UNESCO led its member states to reach a historical agreement on the principles that should underpin the design and use of AI everywhere in the world.

UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence clearly states that it is the duty of governments worldwide to ensure that AI always adheres to the principles of safety, inclusion, diversity, transparency, and quality.

Education has a special obligation to be finely attuned to the risks of AI — both the known risks and those only just coming into view.

At this moment, we must not be so dazzled by its evolutionary leaps that we are ignoring these risks, yet through a balanced approach to AI, we should be able to unlock its potential for learning improvement and the future of education.

Stefania Giannini is the Assistant Director General of Education at UNESCO.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.