Arabic is not just a language spoken in Arabic-speaking countries. It is a growing language within Europe’s own borders, and education policy should reflect this reality, Dr Carine Allaf writes.

Children who grow up in a supportive environment speaking two or more languages are more perceptive and intellectually flexible than those who speak one language, according to numerous research studies.

In Europe, language policy in education appears favourable, especially if compared to language policy in schools in the United States.

Students across Europe begin studying their first foreign language as a required school subject between the ages of 6 and 9.

Studying a second foreign language for at least one year is compulsory in more than 20 European countries.

This is in stark contrast to the situation in the US, where only about 20% of students in primary and secondary schools are enrolled in a foreign language.

But perceptions of foreign languages and the difficulties of teacher supply offer a glimpse into the complexities of the current situation in European education.

Language learning comes with a number of benefits

What to say to someone who would say, "learning English is enough; why learn another language?"

There are neurological, economic, academic, and social advantages to learning an additional language and being bi- or multi-lingual, according to research data from the Council of Europe.

Learning a second language changes the brain’s physical structure, and those who speak more than one language are viewed more favourably for employment.

Not only are their skills useful, but they also demonstrate an ability to work with different types of people and are adaptable.

Bilingual speakers outperform their counterparts on standardised tests, and those who speak multiple languages can communicate with more people around the globe. Their worldview is quite different from their monolingual counterparts.

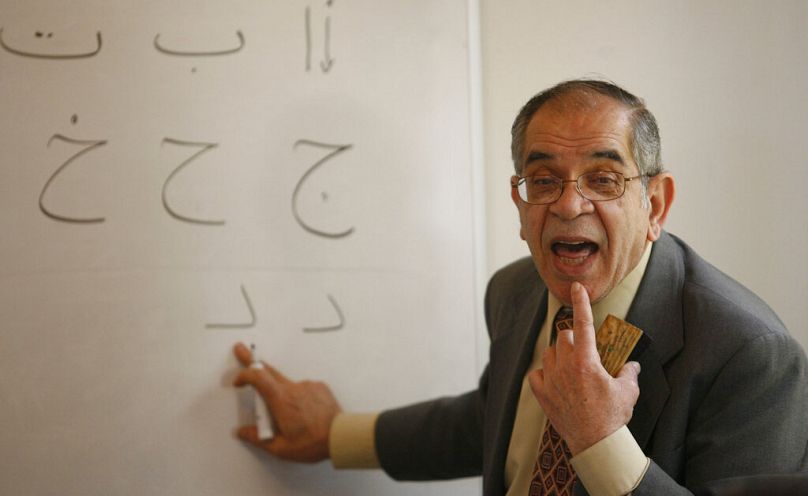

There should be more room for Arabic learning

Despite a strong research base on the benefits of speaking more than one language, and despite strong language policy to teach languages across schools in Europe, the existing infrastructure focuses on languages like Spanish, French and German (and other official EU languages) with little, if any, emphasis on languages like Arabic.

Learning another language isn’t the main argument that needs to be made – the argument is that a common option for an additional language needs to be Arabic.

In theory, European language policy is to provide “multilingual and multicultural of high quality from nursery level to the Baccalaureate, fostering a European and global perspective to educate children of different mother tongues and nationalities.”

Yet, in practice, while there is a strong appetite for language learning, the existing ecosystem for Arabic in schools across Europe — and, I would argue, the world — leaves much room for growth.

Considering all of this, there are two main areas that need to be addressed as just a first step to mainstreaming Arabic learning in public schools.

Arabic language learning is rife with misconceptions

First, there is the perception of the Arabic language. Yes, Arabic is not an official language of the EU and, as such, is not explicitly named in European language policy in schools, mainly due to its perceived value.

The value of learning Arabic, as it stands right now, seems to only be related to religion, the Middle East, or national security.

The fact is, the majority of Muslims do not speak Arabic.

Actually, the top five countries with Muslim populations are not Arabic-speaking countries and are not technically in the Middle East.

Furthermore, there are 422 million people around the world who speak Arabic, and it is an official language of 22+ countries, affirming it as a global language.

And Arabic is not just a language spoken in Arabic-speaking countries. It is a growing language within Europe’s own borders. Education policy should reflect this reality.

It's not just a heritage language

When it comes to being taught in primary and secondary schools, however, the global standing of Arabic remains as a community, heritage, or mother tongue language that exists on the margins of mainstream schools and curricula.

There is a small chance, if any, that Arabic would be offered as a global language at any public primary and secondary school.

And while some countries offer some Arabic instruction for those who come from Arabic-speaking families, more often, it is taught in informal settings on weekends and outside of school hours, with no robust teacher training, curriculum, or oversight.

Yet, elite private schools and universities such as Sciences Po or Polytechnique in France offer Arabic as a global language to their students.

We are witnessing an imbalance in the perception of Arabic language offerings in schools – on the one hand, it is an elite offering, and yet, on the other hand, it is spottily offered for heritage speakers.

Who teaches Arabic in Europe?

Second, and related to the perception, is the availability of dedicated and qualified Arabic teachers.

When students recall their favourite subjects, it is because of a memorable teacher. If schools recount popular classes, it is also most likely because of the teacher that has built that program.

The teacher is the backbone. While there may be plenty of Arabic speakers, finding strong Arabic educators is a huge challenge.

Finding teachers with the proper qualifications is even more difficult. In our experience at QFI, we have seen programs crumble when key teachers leave – and this is not only the case for Arabic but for all subjects.

But how many Arabic teachers have you met?

Not many; the path to becoming a certified teacher isn’t an easy or clearly chartered one, resulting in a low teacher supply.

In some European countries like Sweden, schools locate teachers already in the country coming from Arabic-speaking countries and train them to become Arabic teachers.

And in Spain, there is an existing agreement with an Arab country that sends Arabic teachers to work in schools.

Those teaching can make all the difference

In other contexts, a school that wants to offer Arabic is just happy to find any Arabic speaker who is available to teach.

Often, those teachers’ language skills aren’t assessed, nor is their understanding of teaching pedagogy and methodology. They may receive some training, but it is often not Arabic-language specific.

And this is what brings us back to an earlier statement made “When students recall their favorite subjects, it is because of a memorable teacher.”

Memorable Arabic language teachers need support through their professional life cycle – beginning when they themselves are learning Arabic and considering a career path.

Pre-service programs should offer Arabic methodology courses, as well as courses on basic classroom management and brain development.

Few schools of education or teacher preparatory programs offer such courses. These preparatory programs should frame their offerings with accessible language teaching research that draws from other languages and discussions on the nuances of Arabic.

Frequent teaching observations and touchpoints are the heart of any good teacher training program.

Growing as a teacher requires self-reflection, observation and feedback, and a teacher needs a community of practice to learn from and grow with.

The world is changing, and our views should, too

Perceptions are changing because the world is changing.

It is time to move beyond stigmas such as Arabic is "difficult," only for "heritage" students, and has no utility.

Education policies in practice need to reflect the Council of Europe’s commitment to plurilingual and intercultural education.

Teachers need support and encouragement to build long-lasting Arabic programs that will equip learners with openness to languages and cultures and 21st-century global competencies.

No, English is not enough. In today’s interconnected world, multilingualism, and more specifically, learning Arabic in public schools, is more beneficial than ever.

Dr Carine Allaf is a Senior Programs Advisor at QFI, a Washington DC-based organisation committed to advancing the value of teaching and learning Arabic as a global language.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.