This Monday, humanitarian access will be in the spotlight at the European Humanitarian Forum. The discussions must translate into action, with the EU and its member states driving the necessary changes, IRC's Harlem Désir writes.

Today, a record 339 million people are in need of humanitarian aid.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Yet, the barriers to humanitarian access — in other words, the ability to reach and deliver assistance to those who need it — are increasing, making it harder than ever for organisations like the IRC to reach the most vulnerable.

Alarmingly, this is not a topic that often makes headlines. Aid denial is complex, multi-faceted, and under-recognised.

However, in 2022, millions of people in more than 80 countries were unable to receive aid due to access constraints, and more than 300 humanitarians were attacked — a 50% rise above the 10-year average.

The impact on people in humanitarian need is immense.

The risk of kidnapping, intimidation and murder of aid workers is more real than ever

Our colleagues at the IRC and other organisations are at risk of being kidnapped, threatened, arrested and even killed while seeking to provide life-saving aid.

That is before taking into account the administrative barriers — the time and effort needed to secure travel permits, visas and all the other documents required to deliver assistance — which also need to be overcome in order to establish and maintain access to people in need.

In stark contrast, when humanitarian aid is able to reach people at risk of hunger and starvation, it can save lives and prevent humanitarian crises from worsening or spiralling out of control.

In early 2022, shortly after the shift in power which saw the Taliban return to control of Afghanistan, about 6 million people in the country were on the brink of famine.

International donors stepped up to provide nearly double the funds required for the response and put in place important exemptions offering clarity on sanctions.

This swift, coordinated action allowed humanitarian actors on the ground, like the IRC, to deliver food and support to some 21.5 million people.

While the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan remains dire — particularly for women and girls — and requires continued engagement from the international community, these actions have, for now, prevented the country from sliding into famine.

Restricting aid delivery is being increasingly used as a war tactic

Yet, too often, the denial of aid is not an accident — it is increasingly being used as a deliberate weapon of war, both by state and non-state actors.

We’ve recently seen this play out in Ukraine as civilians in the city of Kherson, where the IRC is now providing assistance, were besieged and denied access to aid.

In Somalia, armed opposition groups regularly restrict humanitarian aid deliveries from reaching their targets and have even been reported to burn food deliveries.

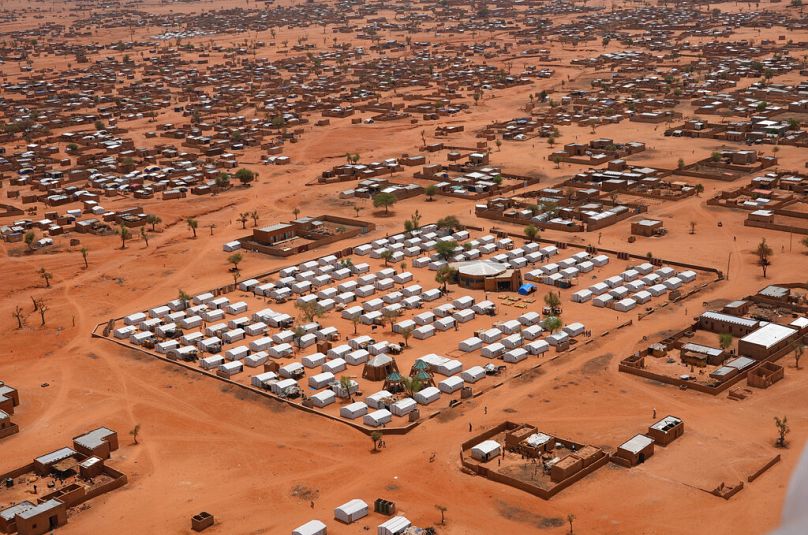

And in Burkina Faso, the increasing number of cities besieged is driving shortages of basic commodities, including food, forcing people to risk their lives to collect wild leaves to eat, while farmers cannot access their fields.

As awful as these examples are, humanitarian workers have effectively been silenced from speaking out about this denial of aid.

European Union and its member states can drive the change

Those in the crosshairs — NGOs and even the UN system itself — cannot take on these threats alone, given the risks to their aid operations in difficult environments and to the safety of their staff.

Constraints on humanitarian access also reflect changing geopolitical and political dynamics in countries impacted by crises.

The proliferation of non-state armed groups means there are now more actors for humanitarians to negotiate with than ever before.

Yet, these groups are sometimes suspicious of humanitarian work or unaware of humanitarian organisations’ commitments to independence and impartiality.

This Monday, humanitarian access will be in the spotlight at the European Humanitarian Forum, EHF, hosted by the European Commission and the Swedish Presidency.

These discussions must translate into action, with the EU and its member states driving the changes needed to ensure humanitarian assistance can be delivered swiftly and effectively without fear of reprisal.

Let's take politics out of aid access negotiations

There are three key steps they can take to ensure this happens.

Firstly, EU leaders should follow the lead of Crisis Management Commissioner Janez Lenarčič in exploring the creation of independent monitoring mechanisms to shine a light on contexts where aid is denied — examining where this is happening and what barriers need to be lifted.

The IRC is calling for the establishment of an Organisation for the Protection of Humanitarian Access, which could take on fact-finding missions and systematic reporting on barriers imposed around the world.

This would take the politics out of access negotiations and help guard life-saving humanitarian work from the politics of member states, including those perpetrating access constraints.

Secondly, the EU and the broader international community should put access at the heart of their humanitarian diplomacy efforts.

This includes engaging with states and, where possible, working on the ground with non-state actors to secure commitments to the promotion and protection of humanitarian access.

The EU has provided leadership on this front in Yemen through its leadership of the Senior Officials Meetings on access.

More recently, despite not recognising the Taliban-led administration in Afghanistan, the EU has restored its physical presence in Kabul to ensure that life-saving aid can be delivered to people in need.

The situation is bound to deteriorate even further

Finally, the UN is not always able to negotiate effectively for NGOs.

However, civil society organisations may not have the training or resources to develop access strategies or engage in direct negotiations with conflict actors.

The EU can play a vital role in plugging this gap.

Supporting national and international NGOs with financial support and training so they can negotiate access on their own terms will help to ensure aid can be delivered to those who need it most.

It’s vital that EU leaders seize the opportunity of the EHF to drive progress towards overcoming these barriers.

If we fail to stop the situation from deteriorating further, the number of people in humanitarian need will soar even higher still next year, and more humanitarians will lose their lives seeking to support them.

Harlem Désir is the International Rescue Committee’s Senior Vice-President, Europe. Previously, he was the founder and president of SOS Racisme, a Member of the European Parliament, the French Secretary of State for European Affairs and OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.