On the other side of COVID-19, Central Europe's sluggish economies need to diversify, work together and make room for innovation to thrive, says public sector advisor Soňa Muzikárová

The delta variant has taken the region of Central and Eastern Europe by storm. The third wave of the pandemic has ripped through Slovakia, Czechia, and Hungary with breathtaking force, causing unprecedented surges of new daily infections, leaving ICUs overwhelmed, and sending some countries back into lockdown.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The region’s vaccination rates are the EU's lowest, and it has recorded some of the highest death tolls, according to European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control data. In the meantime, a new, potentially high-risk variant has emerged and is making its way around the world.

Once robust economic performers off the back of car and vehicle-parts manufacturing exports and inflows of foreign money, these countries' growth model now appears to have largely fizzled out.

These economies are now plagued by a host of structural issues, including polluting industry, dated infrastructure, declining demographics, talent outflows, and absent innovation.

Strength Turned Weakness

At six to seven per cent annually, these transition economies displayed some of the fastest GDP growth rates in the world prior to the 2008-2009 financial crisis, enjoying rapid convergence rates and newly-earned respect on the global stage.

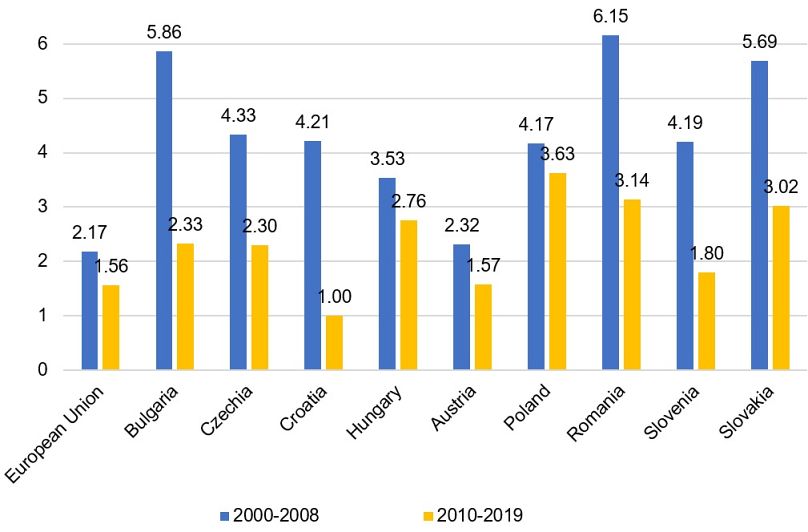

But the financial crisis laid bare some of the prevailing growth model’s vulnerabilities. It sent these economies tumbling back in 2009, dragged down by a double-digit collapse in exports and amplified by the procyclicality of the auto industry. Average growth rates halved in the decade after the crisis in many Central European countries.

Figure 1. Growth rates in Central European countries post-recession

(Chart shows average annual GDP growth rates from 2000 to 2009, and 2010 to 2019)

Slovakia, Hungary and Czechia share a strong core competency in automotive manufacturing, as home to such leading names as Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler, KIA, Skoda, Peugeot PSA and Jaguar Land Rover. A staggering share of the region’s car and vehicle part exports end up in Europe.

But a high degree of trade openness, a mostly undiversified export portfolio, the limited geographical scope of export partners, and tight cross-border production links lead to an over-exposure to shocks.

The recent global shortage of microchips that paralysed Europe’s car production and shook up auto sales is another case in point.

Meanwhile, the region’s governments have struggled to comply with the aggressive timeline of the EU’s Recovery Facility - the massive temporary corona rescue fund – which links cash disbursements to reforms, in the hopes of catalysing Europe’s transition to green and digital and fostering long-term resilience.

The Slovak recovery plan's execution currently lags behind in key strategic areas, including higher education reform and the reform of the judiciary.

Hardest to Start a Business

There is broad agreement among economists and policy practitioners that greater economic complexity and the increased use of technology will be needed for these countries to snap out of the present growth model. This in turn is predicated on the continuous improvement of education, training, research, and innovation.

Against such a backdrop, the basic tenets of an innovation ecosystem must be in place: diverse, deep and abundant talent pools, start-up capital, rich networks, functional support services, a strengthened community, and a risk culture. These will enable the rise of fresh, high-growth start-ups in the region to drive new value creation.

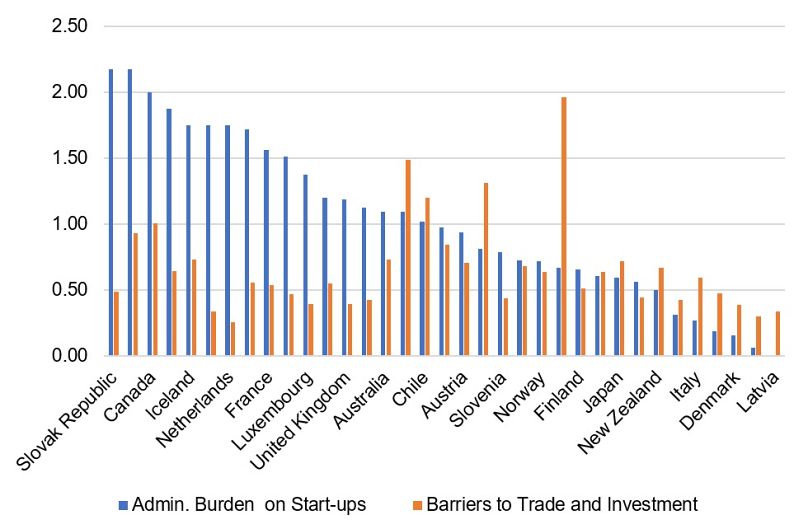

Here, most of Central Europe would be building largely from scratch. According to latest data, Slovakia comes out as the hardest country in which to start a business in the OECD region, owing to a mix of burdensome procedures, time, cost, paid-in minimum capital to start a limited liability company.

Figure 2. Economy-wide values for 2018

(Chart shows Product Market Regulation (PMR) values, measure the regulatory barriers to firm entry and competition, in a series of countries in 2018)

Slovakia scores equally anaemically when it comes to education outcomes, not only lagging behind its EU peer group but worsening over time.

Venture capital to finance new inventions is rare and scarce across the region, with the bulk of financing traditionally provided by the banking sector. The general appetite to take risks is low, perhaps a legacy of the communist past.

A Political Opportunity

Creating a one-stop-shop for innovation is the leading policy choice for the region.

In terms of scope, it would leverage Central Europe’s similar markets, endowments such as existing capital, labour and technology, and shared core competencies in industrial manufacturing.

The small markets would benefit from enhanced scale in terms of increased availability of seed capital, management and technical talent, support networks and services, and regulatory policy coordination (for instance in fiscal incentives, the relaxation of employment protection regulations, common schemes to open up public demand, and the deregulation of markets).

Creating third spaces, such as a regional Tech Summit, would promote paragons of entrepreneurship and enhance networking between research institutes, universities, investors, and firms, providing a visible platform for stakeholder interaction.

Anchoring the initiative would be a joint monitoring system to measure and assess the current state of play, track progress, and understand and remove the bottlenecks. This would be important to ensure it truly delivers social value.

Most importantly, central European governments need a shift in mental gear from local politics to mission-oriented collaboration.

Soňa Muzikárová is a lead economist at Slovakia-based think-tank GLOBSEC and a public sector adviser, formerly of the European Central Bank and the Slovak Finance Ministry.