The world held its breath 30 years ago when a group of senior Communist officials attempted to oust Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and flooded Moscow with tanks. The August coup collapsed after just three days and precipitated the breakup of the Soviet Union.

On August 19, 1991, the world held its breath as hundreds of tanks and other armoured vehicles rolled into Moscow in a massive show of force. Communism had crumbled across eastern Europe, but the Soviet top brass seemed determined not to let the USSR go down the same path.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the president of the Soviet Union, was at his holiday home on the Black Sea, his communications with the outside world cut off by his own officials. He had refused their demands for a nationwide state of emergency.

That morning, Soviet citizens had switched on their TVs to a broadcast of "Swan Lake" by the Bolshoi Theatre. Presenters read out a terse statement saying the president was unfit to govern for health reasons. A new State Committee on the State of Emergency was set up to save the country from "chaos and anarchy".

Gorbachev had paved the way for liberal reform, via glasnost and then perestroika at home. Inadvertently he had lit a fuse that saw opposition movements topple the old regimes from Warsaw to Bucharest, and most symbolically, the wall in Berlin.

Now Soviet power was about to be siphoned off to the USSR's 15 republics via a new union treaty, that the president hoped would stop the country from breaking up. But for the coup's plotters, the document sealed its demise.

Memories came flooding back, of brutal repressions in previous decades when Soviet bloc countries dared to defy Moscow: Hungary in 1956, Prague in 1968. Were Soviet troops about to be used in similar fashion in the USSR's own capital?

Yeltsin seizes the moment

On the streets, thousands of people gathered in front of the headquarters of one of the Soviet republics, the Russian Federation. Its leader, Boris Yeltsin, was a popular head of pro-democracy forces.

The politician had recently won Russia's first presidential election. He had been increasingly critical of the Soviet Politburo even as Gorbachev tried to open up the country, and had resigned from the Communist Party the previous year.

These were crucial moments. The KGB's Alpha commando unit was dispatched to surround Yeltsin's residence near Moscow. But the KGB chief Vladimir Kryuchkov, also the coup's mastermind, held back from giving the order to detain him.

Yeltsin was allowed to drive to his headquarters, which his team decided was worth the risk. Upon arrival, his top associate Gennady Burbulis tried to dissuade him from making his next move, believing it might be too provocative and dangerous.

But the politician went ahead, and climbed onto a tank deployed to block the building. There, he delivered an impassioned speech, urging his supporters to stand up to the coup.

"It was in Yeltsin's character to resolutely and unabashedly defend what he considered right," Burbulis said.

The Russian government's HQ, in a high-rise riverside block, was dubbed the "White House" by Muscovites. Now it became a rallying point for the coup's opponents. Some troops surrounding the building even joined the protesters. By late afternoon, most of the armoured vehicles had left.

Tense stand-off as the world watches

At the Soviet news agency Tass, there was reported feuding between pro- and anti-coup factions. But Yeltsin's condemnation of the coup attempt was reported.

That night on state TV, the images of the pro-democracy champion contrasted sharply with the nervous, indecisive coup instigators who had appeared sweating and stuttering before the cameras at a news conference.

Now the world was watching. Yeltsin was backed by leaders of two other Soviet republics, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. There were reports of a crackdown in the breakaway Baltic republics. US President George Bush cut short his holiday, joining other Western leaders in condemning the coup. American aid to the Soviet Union was put on hold.

Already those behind the attempted overthrow had shown signs of hesitancy. The momentum now swung behind the anti-coup protesters. The next day, up to 200,000 converged near the Russian government building, building barricades and defying a curfew.

"There was a lot of excitement, enthusiasm, resolve and a strong belief in our consolidation and eventual victory," Gennady Burbulis said.

Associated Press writer Ann Imse covered the failed coup, and described the atmosphere at the time:

In the rain-soaked streets of central Moscow, many of the protesters engaged in shouting matches with Soviet soldiers.

“We won’t stand for it!” cried Muscovite Alexander Muzhin.

“It’s our army. They will support us,” said Gasha Kolchin, a 20-year-old medical student at Moscow State University, as he rode on a tank in a downtown street, clutching a red-white-and-blue, pre-revolutionary Russian flag.

“We are not afraid. We are sure that democracy will win in our country,” he said.

Tanks and troops withdraw as anti-coup protesters win the day

In a key development, 1,000 armed police cadets were deployed to Moscow to defend Yeltsin's headquarters by Andrei Dunayev, another ally. He said that helped discourage the coup plotters from using force.

"They decided there would be too much blood," he said.

But blood was spilt: three protesters were killed and others wounded in a clash between troops and protesters in a tunnel near the Russian HQ. Demonstrators blocked the streets with buses, fearing an armed convoy was heading to storm the building.

However, hours later, Soviet Defence Minister Dmitry Yazov ordered the troops to pull out of the capital.

Associated Press photographer Alexander Zemlianichenko covered the coup, from the moment he recognised the sound of tanks in the streets, to the exultant celebrations that followed its collapse.

"There was an uplifting and joyous feeling because the coup had failed. Even now, saying these words, I feel those emotions again," he recalled.

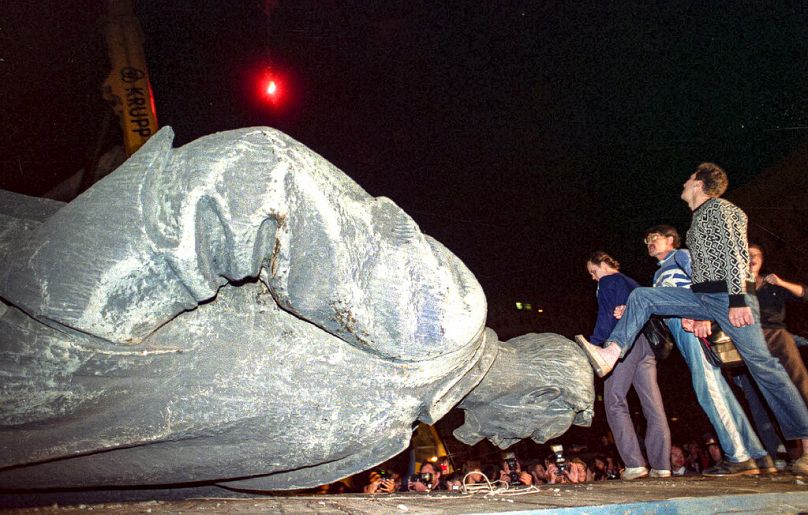

His capture of the moment when demonstrators pulled down the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Soviet secret police, in front of the KGB main headquarters, was a watershed moment that symbolised the collapse of the repressive Soviet system.

Gorbachev cedes power to Yeltsin

On August 21, some of the coup's organisers went to see Gorbachev, still by the Black Sea, to try to negotiate. He refused to see them.

The plotters were arrested and Gorbachev flew back to Moscow the next day. But the president's power was sapped. Boris Yeltsin was now calling the shots.

Andrei Grachev was Gorbachev's spokesman in 1991. "He was kept prisoner for three days by the organisers of the coup, but when he was freed and had the possibility to return to Moscow, he was already the hostage of Yeltsin, because he owed to him his liberation," he said.

"Yeltsin became the number one political actor on the Soviet scene."

Within months, Gorbachev had stepped down and Yeltsin and the other republic leaders had declared the Soviet Union defunct. The coup organisers were put on trial but were granted amnesty in 1994.

Death of the USSR... the Putin era is born

Now 90, Mikhail Gorbachev has spoken with bitterness about the coup, describing it as a fatal blow to the Soviet Union. In a statement issued on Wednesday, the former president said the coup organisers "bear a large share of responsibility for the country's breakup".

Another prominent figure who lamented the USSR's demise was appointed in 1998 by Boris Yeltsin as head of the new Federal Security Service (FSB), the KGB's domestic successor. Vladimir Putin has described the Soviet collapse as the "greatest political catastrophe of the 20th century".

But far from championing the democracy that protesters in 1991 had called for, today's Russian president has been accused by critics of steadily rolling back post-Soviet freedoms during his two decades in power. Opposition has been stifled and key opponents jailed, some killed.

In the last few months, Russian authorities have intensified a crackdown on opposition activists and independent media ahead of the country's parliamentary election in September, which is widely seen as a key part of Putin's efforts to cement his rule for years to come.

Gennady Burbulis, Yeltsin's former aide, regrets his country's failure to get rid of its authoritarian past.

"Thirty years later, we are still stuck in the post-imperial mindset,” Burbulis said. "Power has become the ultimate value for some, along with restrictions of freedoms and controls over civil society, not to mention direct restrictions of freedom of election."

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.