Europe needs a recovery plan. Failing to achieve one would not just damage solidarity but also the Eurozone (and maybe even the EU) irrevocably, writes Darren McCaffrey.

On Monday, Brussels Airlines planes finally took to the skies again and the good news for the airline was that almost all of its flights were full.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Belgium's national carrier ran 22 flights on June 15. The first departure to Rome took off at 7:30 am and every seat was booked.

“Everything is going according to plan,” said Dieter Vranckx, the CEO of Brussels Airlines, adding that he is satisfied with the resumption of activities.

“After three months of inactivity, today is an important day. We have full flights almost everywhere. That is good.”

Passengers were made up of the usual business travellers and even a few keen tourists. Future bookings are increasing, too, with people wanting or needing to move around again.

“They are increasing by almost 50% every week. There is a clear desire to travel, to discover other countries, to get out of Belgium,” Vranckx said.

Life in Europe is far from normal at the moment, but there is a sense that it is moving in that direction. However, beyond the major health crisis, the continent still faces a deep and possibly prolonged recession of a magnitude not seen for nearly a century. A recession that will see businesses fold, substantial job losses and mounting government debt.

For months now the EU and its member states have been debating a recovery plan. And tomorrow, EU leaders meet again, to discuss the European Commission’s plan to spend a whopping €750 billion to tackle the economic fallout; mostly made up of grants, rather than loans. What's significant, is that that money will be raised as shared European Union debt. It is part of a wider package running into trillions of euros, including repurposing much of the EU budget over the next seven years.

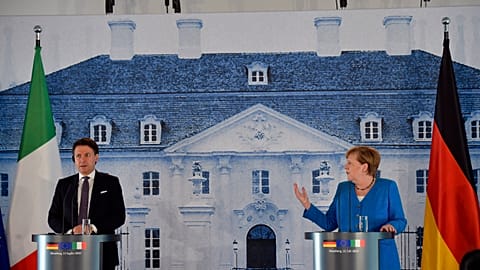

However, don’t expect a deal tomorrow, or possibly even next month when leaders hope to meet in person for the first time since February. The current plan is backed by Europe’s four biggest economies, Germany, France, Italy and Spain, but not by the so-called “frugal four” of The Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and Denmark. Their leaders wrote a letter to the Financial Times this week calling for a “realistic level of spending” and for all the money to be paid back. And there seems to be mounting concern in the east too, particularly among the Baltic nations.

It is the Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, who has become the leader of the rebel pack in recent months; championing EU fiscal discipline and pushing back on integrationist attempts to mutualise debt or relax deficit rules.

There is domestic pressure back home. His four-party coalition no longer holds a majority in the Dutch parliament and Eurosceptic forces have been quick to seize on any sign of compromise. Also, the current proposal seems to be wildly unpopular with voters in The Netherlands. One poll found that 61 per cent did not support the EU recovery plan. In fact, four per cent of voters said they were happy with the proposal. “It’s not just Italy and France who have populists; we have them too,” one Dutch diplomat quipped.

Europe needs a recovery plan. Failing to achieve one would not just damage solidarity but also the Eurozone (and maybe even the EU) irrevocably. It would tear at the seams of the Union and, undoubtedly, prolong what will be a very deep recession. But, can a deal be struck? The sheer complexity of the proposals will take member states time to digest, but for Brussels, it is the complex competing interests which are the most troubling, with fears they might be too great to overcome.

Darren McCaffrey is Euronews' Political Editor.