Digital colourist Marina Amaral, the woman behind the Faces of Auschwitz project, explains why her work colourising pictures of Auschwitz inmates is so vital, despite the toll it takes personally.

Her blue eyes are fixed in fear, staring out from beneath a closely-shaven head into the distance. Instead of her name, a number is displayed on a board beside her. The only other information it posits is that she is Polish and her location: Auschwitz.

The haunting image of Czesława Kwoka, a 14-year-old Polish Catholic, was taken just months before she perished in the most infamous extermination camp in the Nazi state.

As world leaders and the last survivors gather on the week that marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the burden of bearing witness to the horrors of the Shoah is increasingly falling on the shoulders of younger generations, like those of Marina Amaral.

The Brazilian digital colourist first came to prominence internationally when the colourised image of Kwoka and her life story went viral two years ago. The impact of the photograph sowed the germ of an idea which resulted in the Faces of Auschwitz project, a collaboration with the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, academics, journalists and volunteers.

“I created the project in 2018 after finding and colourising Czesława’s photo. Her story went viral around the globe and I understood that I needed to do something bigger. I could not do this with a single photograph. I wanted to tell more stories and individualise more people.”

A self-taught specialist, Amaral developed and perfected her craft through trial and error using Photoshop as a hobby to bring black and white photographs to life in vivid technicolour; from defining moments in history like the D-Day landings to portraits of historical figures such as John F Kennedy and Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

While the colourisation of historical images captured in monochrome is not without its critics, Amaral is a firm believer in the potential digital colouring has to help recapture a lost sense of humanity.

“I think it humanises them,” says Amaral. “They are no longer just numbers or statistics, but are people like you and me. Colours make us feel more empathetic. They help us to connect with the subject in a deeper, meaningful way.

“When we see the photos in colour, there’s no longer an emotional barrier there,” she adds. “These people are suddenly more relatable; more real, flesh and blood - literally.”

Kwoka’s portrait was taken by fellow inmate Wilhelm Brasse, a Polish prisoner and photographer sent to Auschwitz in 1940. In later testimony, he recalled that the teen had been viciously beaten with a stick by a kapo – a prisoner overseer – just before she appeared in front of the lens, the aftermath of which was frozen in time in black and white film.

“You cannot see the blood dripping from Czesława Kwoka’s lip unless you know the story that she was beaten up just minutes before the photo was taken. But now you can see it, and from there, an emotional connection is established.”

Kwoka was deported to the camp, along with her mother Katarzyna, from their village in the Polish region of Zamość, an area designated by the Nazis for use as Lebensraum – or ‘living space’ – for ethnic Germans. Her mother died from unknown causes on 18 February 1943, just two months after their arrival. According to camp records, Kwoka was murdered the following month with a phenol injection in the heart. She was 14 years old.

Hers is just one of nearly 39,000 surviving identification photographs taken by Brasse which are preserved in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum archives, the commissions of Nazi camp officials to document prisoners in case of escape.

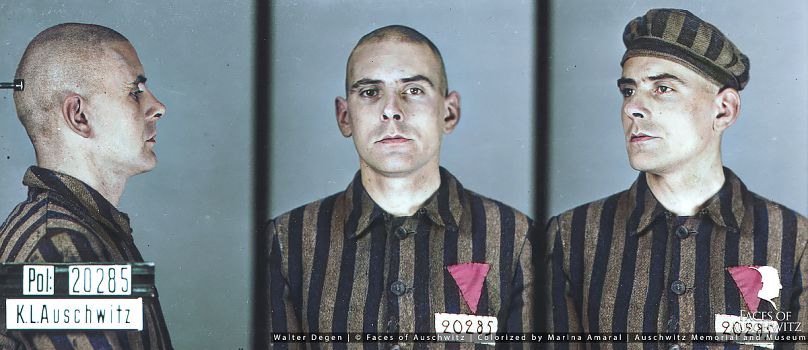

As well as Jews murdered at the camp, the project has also shone a light on the other groups who faced persecution under the National Socialist regime and were among the 1.1 million victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau. The photographs of other prisoners, like Walter Degen, a gay man transported to Auschwitz on the basis of his sexuality in August 1941, or Deliana Rademakers, a Dutch Jehovah’s Witness who died there in December 1942, have helped bring these groups’ stories to life as well.

The process of hand colourising the images on Photoshop can take Amaral from one to three days to complete, after which the image is subjected to an extensive expert analysis to ensure its historical accuracy.

Besides being labour intensive and time-consuming, work on the Faces of Auschwitz project has taken a personal toll on her as well. “I have panic and anxiety attacks after I work on the photographs, something that does not happen when I’m working on other photos,” she says.

“It is not an easy thing to do. I read death certificates; I know what happened to these people. And I need to spend hours looking at their faces.”

Is it a price worth paying? For her, yes. “I guess I just accepted that this is a consequence and I have to live with it, because I believe that we are doing something very important through Faces of Auschwitz.”

Two years on since it was first founded, the aims of the project have never been clearer. “My goal is to help people understand and dive deeper into the story of each victim, and into the story of the Holocaust itself,” Amaral says.

“We need to understand how and where it all started. Hate speech was the starting point. We need to see where it can lead to.”