In Northern Ireland, politics and art have long made for natural bedfellows.

In Northern Ireland, politics and art have long made for natural bedfellows. A country historically divided along religious and political lines, both the Protestant UK Unionist population and the Catholic Irish Republican community have utilised the arts in all their forms to express their trenchant viewpoints.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Every 12th of July, for example, orange bands across Northern Ireland celebrate King William of Orange’s significant victory over King James II, the last Roman Catholic British monarch, at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, by leading parades through the streets to the loud, proud sounds of militaristic Lambeg drums.

Republican politicians, meanwhile, often quote Irish poets, with barrister-turned-activist and executed leader of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, Patrick Pearse, a particular favourite. And few traditional music nights go by in Irish pubs, even today, without renditions of Wolfe Tone rebel songs eulogising Ireland’s patriots.

Nowhere are the Unionist/Republican cultural wars more vividly waged, however, than in the visual arts, and in particular public art. Few countries in Europe, in fact, value their mural paintings quite like the Northern Irish.

Painted onto the gable wall of a residential building in a staunchly Unionist area of East Belfast, this mural on the Lower Newtownards Road is dedicated to the Ulster Freedom Fighters (East Belfast Brigade), the paramilitary arm of the Ulster Defence Association, both now defunct. The UFF conducted an armed campaign for 24 years during the Troubles and was responsible for the deaths of over 400 individuals.

Painted onto the gable wall of a residential building in a staunchly Unionist area of East Belfast, this mural on the Lower Newtownards Road is dedicated to the Ulster Freedom Fighters (East Belfast Brigade), the paramilitary arm of the Ulster Defence Association, both now defunct. The UFF conducted an armed campaign for 24 years during the Troubles and was responsible for the deaths of over 400 individuals.

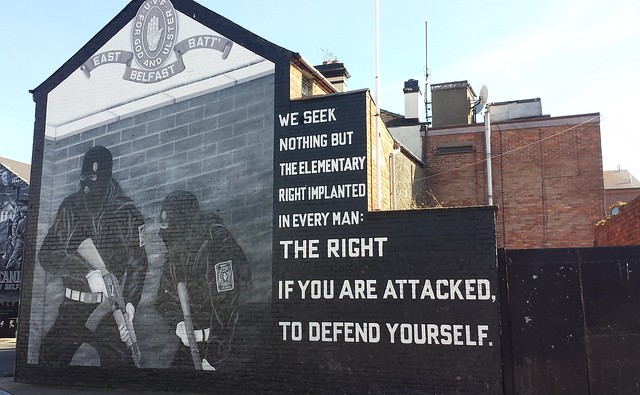

Also on the Newtownards Road, this mural depicts members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (East Belfast Battalion), the second largest Unionist/Loyalist paramilitary group, carrying semiautomatic weapons and wearing balaclavas. The UVF conducted an armed campaign for 30 years and was responsible for over 500 deaths. Both the UFF and UVF officially ended their campaigns in 2007.

Also on the Newtownards Road, this mural depicts members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (East Belfast Battalion), the second largest Unionist/Loyalist paramilitary group, carrying semiautomatic weapons and wearing balaclavas. The UVF conducted an armed campaign for 30 years and was responsible for over 500 deaths. Both the UFF and UVF officially ended their campaigns in 2007.

In villages, towns and cities across Ulster, gable walls of residential buildings in working-class areas have traditionally provided the canvas for artists commissioned by paramilitaries to mark out territorial boundaries and celebrate and commemorate their inglorious dead.

Curb stones painted red, white and blue (Unionist), or green, white and orange (Republican), invariably lead toward murals depicting gun-tooting paramilitary ‘heroes’, graven-faced political leaders holding court at the lectern and events such as the Battle of the Somme and the Easter Rising.

More recently, however, the old sectarian (and, in some cases, frankly terrifying) imagery spotted in almost every quarter of the city has begun to be replaced by more politically-expedient images that reflect Northern Ireland’s transformation from the Troubles to the 21st century by way of the Good Friday Agreement.

In 2017, city sightseeing bus tours stop off at the big landmarks, such as Titanic Belfast, Queen’s University and City Hall, but the murals are never off the itinerary, with the Republican Falls and the Unionist Newtownards Road areas Meccas for those interested in public art.

Nearby, this mural erected by the Ballymacarrett Somme Society pays tribute to the Ulster-born ‘fathers, sons, husbands and brothers who paid the supreme sacrifice’ while fighting at the Somme during the First World War. These soldiers were derived from the original Ulster Volunteers, a militia formed in 1912 to stave off British Home Rule in Ulster.

Nearby, this mural erected by the Ballymacarrett Somme Society pays tribute to the Ulster-born ‘fathers, sons, husbands and brothers who paid the supreme sacrifice’ while fighting at the Somme during the First World War. These soldiers were derived from the original Ulster Volunteers, a militia formed in 1912 to stave off British Home Rule in Ulster.

Weapons decommissioned, paramilitaries disbanded, government devolved, power shared, peace established, tourists welcome, Belfast’s urban landscape is also being reclaimed by a new generation of liberal, secular, European visual artists for whom the terms Unionist and Republican do not apply.

Here, then, is a visual run through of the changing face and aesthetic of Belfast’s many murals, from the Newtownards Road to the cosmopolitan Cathedral Quarter.

Arts and community organisations in East Belfast, as elsewhere in the city, are reclaiming communities and replacing sectarian imagery and slogans with new murals promoting diversity and inclusivity. This environmental mural on Connswater Street, off the Newtownards Road, was designed by local artist Hicks and marks the location of an urban community garden.

Arts and community organisations in East Belfast, as elsewhere in the city, are reclaiming communities and replacing sectarian imagery and slogans with new murals promoting diversity and inclusivity. This environmental mural on Connswater Street, off the Newtownards Road, was designed by local artist Hicks and marks the location of an urban community garden.

Directly opposite, this newly completely mural on the gable wall of the EastSide Visitor Centre was designed by local artist Dee Craig and depicts a selection of luminaries associated with East Belfast, such as legendary footballer George Best, musician Van Morrison and novelist Lucy Caldwell.

Directly opposite, this newly completely mural on the gable wall of the EastSide Visitor Centre was designed by local artist Dee Craig and depicts a selection of luminaries associated with East Belfast, such as legendary footballer George Best, musician Van Morrison and novelist Lucy Caldwell.

On the Nationalist/Republican Falls Road in West Belfast is located one of the city’s most visited mural sites. Recently redesigned, it now reveals a timeline of events that led to the 1916 Easter Rising, an armed insurrection led by Irish Republicans with the aim of ending British rule in Ireland. The rising was largely symbolic but featured fighters from Belfast, including several women from the Cumman na mBan female paramilitary organisation.

On the Nationalist/Republican Falls Road in West Belfast is located one of the city’s most visited mural sites. Recently redesigned, it now reveals a timeline of events that led to the 1916 Easter Rising, an armed insurrection led by Irish Republicans with the aim of ending British rule in Ireland. The rising was largely symbolic but featured fighters from Belfast, including several women from the Cumman na mBan female paramilitary organisation.

Just around the corner, on Beechmount Avenue, Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) member Francis Hughes is commemorated in this striking mural, surrounded by fellow Republicans and hunger strikers, protesting the withdrawal of their status as political prisoners. Hughes died on May 12, 1981 in the Maze/Long Kesh prison following a hunger strike lasting 59 days.

Just around the corner, on Beechmount Avenue, Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) member Francis Hughes is commemorated in this striking mural, surrounded by fellow Republicans and hunger strikers, protesting the withdrawal of their status as political prisoners. Hughes died on May 12, 1981 in the Maze/Long Kesh prison following a hunger strike lasting 59 days.

The IRA has long associated itself with other revolutionary, socialist forces and causes around the world, including, controversially, the armed Basque separatist group ETA in the 1980s. Here on Beechmont Street a mural remembers the late Cuban President Fidel Castro, and includes the slogan translated ‘Until forever, Commander!’

The IRA has long associated itself with other revolutionary, socialist forces and causes around the world, including, controversially, the armed Basque separatist group ETA in the 1980s. Here on Beechmont Street a mural remembers the late Cuban President Fidel Castro, and includes the slogan translated ‘Until forever, Commander!’

The cosmopolitan Cathedral Quarter has become the artistic beating heart of Belfast, housing many and varied arts venues and festivals throughout the year. On Talbot Street, almost hidden from view in a private parking area closed off at night, you will find ‘The Son of Protagoras’, by French hyperrealist street artist MTO. This piece reflects the artist’s agnosticism.

The cosmopolitan Cathedral Quarter has become the artistic beating heart of Belfast, housing many and varied arts venues and festivals throughout the year. On Talbot Street, almost hidden from view in a private parking area closed off at night, you will find ‘The Son of Protagoras’, by French hyperrealist street artist MTO. This piece reflects the artist’s agnosticism.

Belfast’s culinary culture is buzzing at present, with a whole host of new and exciting restaurants opening across the city offering a range of international cuisine. This piece on High Street Court, by Australian graffiti writer Smug One, is an astonishingly detailed image of a brooding head chef with his lobster ready for poaching.

Belfast’s culinary culture is buzzing at present, with a whole host of new and exciting restaurants opening across the city offering a range of international cuisine. This piece on High Street Court, by Australian graffiti writer Smug One, is an astonishingly detailed image of a brooding head chef with his lobster ready for poaching.

Blink and you’ll miss it – among the hustle and bustle of central Belfast, opposite the iconic Kremlin gay bar on Donegall Street, this wonderful work by LA artist Christina Angelina frames the Irish News building and was one of 30 murals erected in the city as part of the 2015 Culture Night celebrations.

Blink and you’ll miss it – among the hustle and bustle of central Belfast, opposite the iconic Kremlin gay bar on Donegall Street, this wonderful work by LA artist Christina Angelina frames the Irish News building and was one of 30 murals erected in the city as part of the 2015 Culture Night celebrations.

The Sunflower Public House on the corner of Kent Street and Union Street, just around the corner from Belfast Central Library, is a prime meeting place for the city’s millennials. This humorous update on Vermeer’s portrait ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, by David Creative, is one of several eye-catching pieces in the vicinity. Graffiti beside it reads ‘Abortion Rights Now’, Northern Ireland being the only nation within the UK where abortion remains illegal.

The Sunflower Public House on the corner of Kent Street and Union Street, just around the corner from Belfast Central Library, is a prime meeting place for the city’s millennials. This humorous update on Vermeer’s portrait ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, by David Creative, is one of several eye-catching pieces in the vicinity. Graffiti beside it reads ‘Abortion Rights Now’, Northern Ireland being the only nation within the UK where abortion remains illegal.

Text and photos by Lee Henry