ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

By Fabrice Balanche, associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, visiting fellow at The Washington Institute

In 1990, Iraqi president Saddam Hussein evidently assumed the West would give him a pass when he invaded Kuwait, considering the upheavals accompanying the end of the Cold War. In the previous decade, he had received support from the West and the Gulf oil monarchies in his country’s war against Iran. But the Iraqi leader had miscalculated. Within a few months, a huge US-led military force consisting of hundreds of thousands of troops was deployed to the Gulf to protect Saudi Arabia and liberate Kuwait. The first Gulf war marked the beginning of a period of US regional hegemony that would last two decades, the most striking expression being the Iraq war of 2003–11. With the Syrian war, however, the United States has reduced its regional role.

In the current regional scene, against a lower but still significant US presence, Russia has returned assertively following a post–Cold War hiatus, China is filling in the gaps, and the European Union remains cautious. Room thus remains for Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, each of which wants to expand its regional influence, with or without the help of international actors. Turkey, a NATO member, clearly fell within the Western camp, but it could share priorities with Russia, as today in Syria. Saudi Arabia has demonstrated increasing separation from the United States based on criticisms over Washington’s insufficient involvement in the Syrian war and the conclusion of the Iran nuclear deal. The Islamic Republic, for its part, has emerged from its isolation, aided by Russian and Chinese involvement in the region. Furthermore, the nuclear deal gives Iran additional financial resources and helps normalise its relations with the West.

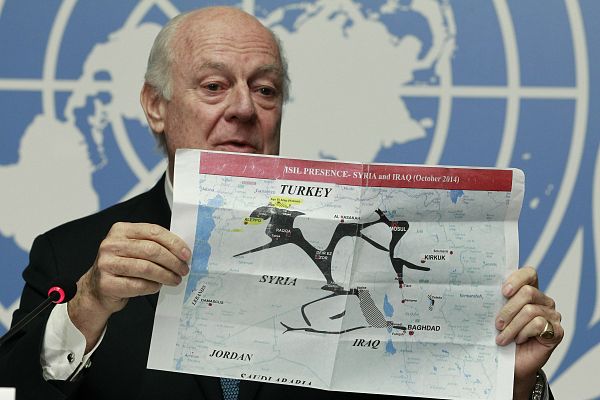

In vigorously reentering the Middle East by way of the Syrian war, Russia has invoked international law to justify its defence of Bashar al-Assad. By this logic, any foreign interference against the government of a sovereign state is a casus belli. China shares such a position. The two Eurasian powers do not want the West, through the United Nations, to intervene in their own fragile peripheries. Although Russia’s maritime base in Tartus, Syria, and its radar stations in the country do not constitute essential strategic interests, they uphold Syria as an ally in a region where conflicts quickly gather international implications. The Chinese, meanwhile, see access to Middle East hydrocarbon reserves as deeply attractive, given their energy needs, whereas the Russians have enough domestic gas and oil production. Finally, in the Sunni Islamic terrorism embodied in the Islamic State, Moscow, Tehran, and Beijing perceive echoes of local destabilizing militants, namely in southern Russia and western China.

Heavily laden #ВМФ #Бф #BF Ropucha class LSTM Alexander Shabalin departs Black Sea & transits Bosphorus en route to #Tartus #Syria pic.twitter.com/GOzc9Cj6Vt

— Bosphorus Observer (@YorukIsik) 3 janvier 2017

The EU’s absence from the Middle East is evident on many planes. In the 2011 Libya campaign, for example, the United States provided 70 percent of operational logistics, despite an Anglo-French presence. In August 2013, France found itself alone in Syria after the British refusal to engage militarily, and especially after the US about-face, when President Barack Obama canceled the bombing of Syria in response to the regime’s chemical weapons attack in the Damascus suburbs. Furthermore, any French or British activism in Syria is hindered by the slowness and timidity of collective decision making within the EU, which itself appears highly dependent on NATO and, therefore, American decisions. Economically, the EU is also relegated to a minor role in addressing the enormous financial capacity of the Gulf oil monarchies and BRICS, as Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa are collectively known.

The Middle East is thus now more internally focused than in past decades, prey to a lasting conflict among the three regional powers, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, which aspire to occupy the spaces vacated by a dwindling Western military-political apparatus.

In October 2013, Ammar Moussawi, the head of external relations for Hezbollah, the Lebanese militant group and political party, stated in an interview that the regional conflict would last a “long” time—with “long” equivalent to several decades in Western terms. Moussawi did not refer directly to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which remains a Hezbollah priority. He did speak, however, of the proxy conflict in Syria, pitting Saudi Arabia against Iran. Although he did not explicitly mention the Sunni-Shiite element, Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah had done so two months earlier, accusing Saudi Arabia of sparking a new fitna(discord). In the Syrian war, Hezbollah and Iran see an existential crisis, with the perceived Sunni offensive supported by Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, states that fear Iran’s rehabilitation and expanded regional reach, as facilitated by the nuclear deal. Iran’s economy will benefit from the lifting of international sanctions, and the Western powers, eager to sign lucrative contracts with the Islamic Republic, will be more tolerant of Tehran’s behaviour than before.

The global resonance of the Syrian war has a precedent from some four centuries ago: the conflict in Bohemia (1618–23), which initiated the Thirty Years’ War. Today, world powers such as Russia, China, the United States, and Europe are assessing their regional interests and the measures they will take to achieve them. The conflict itself, meanwhile, can only grow, as the Yemen example shows, given the freeing up of local actors. But amid the great instability, a new Westphalian order is emerging in the Middle East. Rather than erasing the mistakes of the past a new territorial division could end up being superimposed upon the Sykes-Picot line by which the departing colonial powers split the region.

The views expressed in opinion articles published on euronews do not represent our editorial position.