What is Bahamas Leaks and how big it is?

What is Bahamas Leaks and how big it is?

On Wednesday September 21 the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) released a set of nearly one and a half million documents from the Bahamas corporate registry.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

These included the names of directors and owners of some 175,000 companies, foundations and trusts registered between 1990 and 2016.

ICIJ and its partner media add in a disclaimer that use of offshore accounts is not necessarily illegal or illegitimate.

“We do not intend to suggest or imply that any persons, companies or other entities included in the ICIJ Offshore Leaks Database have broken the law or otherwise acted improperly” it reads.

How does it compare to other recent leaks?

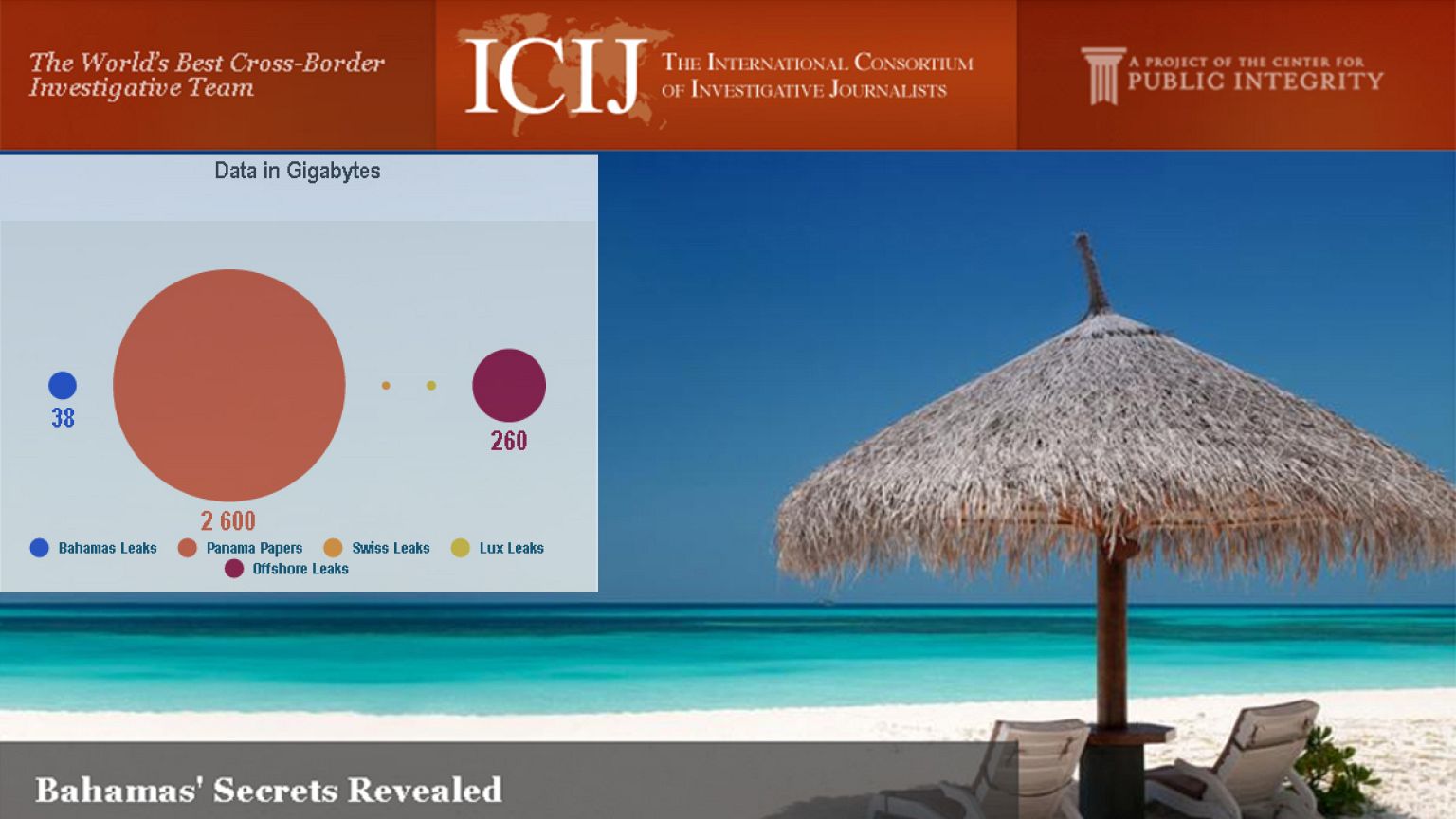

The Bahamas Leaks have been included in the larger “Offshore Leaks Database”, which has information on half a million offshore accounts and businesses, and gathers the data published in the previous leaks, such as the Panama Papers.

The ICIJ has uploaded this database and it’s available for download for everyone.

“We see it as a service to the public to make this basic kind of information openly available,” said Gerard Ryle, the director of ICIJ.

Ryle added that, although most offshore operations are legal, “there is much evidence to suggest that where you have secrecy in the offshore world you have the potential for wrong doing. So let’s eliminate the secrecy”.

Who are the people involved?

The most prominent name in the latest Bahamas Leaks is the former EU Commissioner for Competition, Neelie Kroes.

She appears as a director of Mint Holdings Limited between 2000 and 2009. Kroes didn’t declare this before taking office in 2004.

Mint Holdings is owned by Amin Badr-El-Din, a polo playing ex-advisor to the President of the United Arab Emirates. In 2000 Badr-El-Din intended to buy the international assets ($6 billion) worth of US electric giant Enron as they went bankrupt in spectacular fashion.

In the end, the deal was never completed, and Kroes said she was not paid for her role, as the company never became operational and there had been no board meetings.

But Kroes’ lawyers admit she was a non-executive director and blamed her appearance on company records as “a clerical oversight which was not corrected until 2009”.

The EU’s code of conduct states that “Commissioners may not engage in any other professional activity, whether gainful or not”.

Kroes’ role was therefore a clear contravention of this rule.

Kroes is currently a paid advisor to both Bank of America, and the popular yet controversial ride-hailing app, Uber.

It is understood that she has informed current EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker of what she calls an “oversight”, and according to her lawyers “she will take full responsibility for it”.

Bad timing

This revelation comes at a bad time for the Commission, as former President José Manuel Barroso is being investigated for his current role at the investment bank Goldman Sachs. President Juncker recently criticised his predecessor in an exclusive interview with euronews.

The main sanction available to Juncker in these circumstances is to strip the former commissioners of their pensions, though this action would require approval from the European courts.

Other political figures named in the leaked documents include Colombia’s minister of mines and energy between 1999 and 2001, Carlos Caballero Argáez.

Mossack Fonseca, the law firm whose leaked files formed the basis of the Panama Papers, appears as one of the most active among 539 registered agents.

Explore the database for yourself