Benjamin Von Wong is a Canadian artist who has been turning plastic waste into spectacular constructions with global impact for a decade. Euronews Culture spoke with the environmental activist about his fight to use recycling to bring about climate change policies.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

On a sunny August morning in Geneva, as diplomats crowded the corridors of the United Nations for another round of arduous negotiations, something appeared on the square in front of the building that no one could ignore.

A giant figure sat hunched over, chin supported on his hand - in a pose the whole world knows from Rodin's The Thinker. But this is no bronze casting. This Thinker is six metres tall and created from recycled plastic. In one hand he clutches a crushed bottle, in the other he holds a child. At his feet, trapped in a strand of DNA, the figure of Mother Earth wriggles.

This sculpture is entitled 'The Thinker's Burden'. It is not only a work of art. It is an expression of remorse. A warning. A mirror.

Behind the installation is Benjamin Von Wong, a Canadian artist and activist who for a decade has been turning plastic waste into spectacular constructions with a global reach. His works do not go into galleries. They appear where politics and the future of the planet are played out: at climate summits, UN conferences and treaty negotiations.

"Art has the power to awaken curiosity, awe and wonder," says Von Wong. "But above all, it reminds us why what we do matters. And what we lose if we fail."

From rocks to revolution

Von Wong did not grow up with the idea of saving the world through art. He studied mining engineering at McGill University and began his career underground.

"After three and a half years, I woke up and realised I didn't even know why I was going to work," he recalls. "But I knew one hundred per cent that I didn't want to be doing this in ten years. To be sitting at a bigger desk, earning more, but still just digging holes in the ground."

So he quit everything. Without a plan. First he tried acting. Then photography. Eventually he found himself creating fantastic installations that combined art, technology and vision. By 2015, he already had half a million online followers and the status of 'creator of spectacular images'.

But fame did not satisfy him. "I kept asking: why am I actually creating just cool stuff for the wow effect alone?" he recalls. The answer pushed him towards environmental activism.

He absorbed documentaries, explored the science of plastic pollution and climate change. He decided to combine art with environmental impact.

It wasn't easy at first. NGOs were sceptical. Activists wondered what contribution a fantasy photographer could make. So Von Wong did what engineers do best: he proved that it was possible.

The result: art that not only dazzles, but also demands reflection.

Artist, Strategist, Conductor

Von Wong calls himself a conductor rather than an artist. "I'm not a guy who tinkers alone in the studio," he laughs. "I'm the person who comes up with an idea that hopefully comes at the right place at the right time, with the right story, so that it can make the biggest impact." His creative process is as logistical as it is artistic: he raises funds, recruits volunteers, coordinates with NGOs, negotiates permits, and develops strategies for media coverage.

Producing an installation costs tens and sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars. But, he says, the sponsors are actually funding more than just the sculpture. "They are buying the story, the strategy and the impact it brings with it."

"I constantly get requests from people: come and make something out of our rubbish. But my art only works if it's in the right place, at the right time and with the right story."

Although plastics have become his most visible medium, Von Wong sees his art as part of a broader climate story. He has chased tornadoes to highlight the chaos of climate change. He has made underwater photographs with sharks to draw attention to the collapse of biodiversity. He is obsessed with symbols that link everyday waste to the consequences for the planet.

Trash as material, planet as canvas

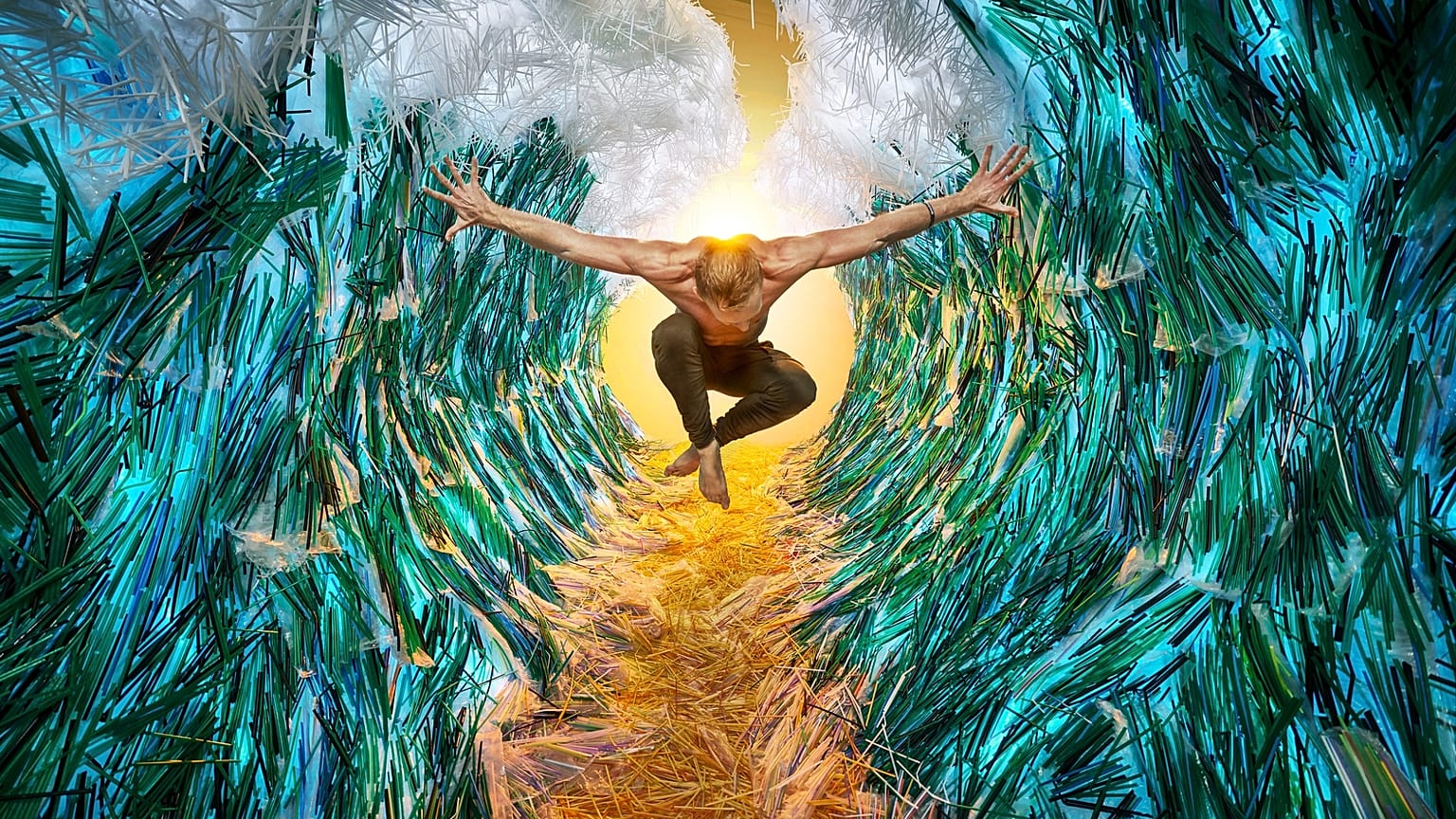

Von Wong's catalogue reads like a series of impossible stunts.

A mermaid trapped in 10,000 plastic bottles - a symbol of an ocean suffocating in waste.

168,000 straws arranged in a record-breaking "Strawpocalypse" installation, entered in the Guinness Book of Records.

A giant levitating plastic tap, unveiled during the UN negotiations in Nairobi, from which rubbish is constantly "flowing out".

A multi-storey Jenga tower, built at COP16 in Colombia, showing the fragility of biodiversity. These are just some of the artist's projects.

"From a distance, my art looks beautiful," says Von Wong, "but when you get closer, you see that it's made of rubbish. That's what defines my work - this balance between beauty and tragedy. You feel a little bit uncomfortable and at the same time you feel drawn to it. And I think that juxtaposition of feelings is what I'm always trying to convey."

Plastic in numbers

⦁ 430 million tonnes of plastic are produced annually.

⦁ 2/3 of plastic produced ends up in landfills or in the environment.

⦁ Only 9% of plastic is recycled.

⦁ By 2050 there could be more plastic in the oceans than fish.

A monument to political inaction

The Geneva sculpture was his most political work. Every day, volunteers added new waste to it, making the sculpture literally 'weigh' more and more. It is a vivid metaphor for negotiations that dragged on indefinitely.

"We wanted to show the increasing cost of inaction" explains Von Wong.

The reach of the piece was staggering - 5.5 billion impressions across 2,000 news articles. Even corporations such as Unilever, often criticised for their use of plastic, shared the graphic.

Rarely can one sculpture break down such a large divide, yet Von Wong's work has become a symbol of unity.

One delegate remarked privately, "It was impossible to walk past it".

Matthew Wilson, Ambassador and Representative for Barbados, in one of Von Wong's films, warns: "More than 16,000 chemicals are used in plastics and at least 4,200 of them are harmful to health."

Maria Ivanova of the Plastics Center at Northeastern University emphasised in Geneva: "People don't change their minds through facts. They change through their emotions. And this is where art plays a key role."

Michael Bonser, head of the Canadian delegation, also found the work "extremely moving", which reminds delegates every day what they are fighting for inside the negotiating room.

For Von Wong, the aim was not to embarrass the negotiators, but to remind them of the bigger picture: health, human dignity and future generations. "We are not creating a treaty just to have one," he says. "We are creating it to protect the health of people and the well-being of all future generations. Until the treaty is able to provide that, it is not good enough."

Von Wong knows that raising awareness is no longer enough. "Ask anyone today: is plastic a problem? Everyone will answer in the affirmative. The challenge now is to push for policy and systemic change." That's why his art has moved from awareness campaigns to treaty summits, from Instagram to negotiating tables.

Are climate concerns taking a backseat?

Climate issues, once at the forefront of global politics, often seem overshadowed by wars, economic instability and rising authoritarianism.

Asked if he thinks environmental issues have fallen off the list of political priorities, Von Wong does not hesitate for a moment. "Definitely," he replies. "It is important to remember in the context of the failure of the global plastics treaty negotiations in Geneva that the world we live in today is very different from the world we lived in a year ago. Hostility towards ecology is greater today than ever. Financial cuts are widespread. Governments are dealing with inflation, political crises. In the US, the presidency is pro-business, anti-environment. Add to that the wars that are consuming media attention. The environment is in a difficult position."

But he doesn't see this as a reason to stop acting. On the contrary. "Not all battles are undertaken to be won. Some have to be fought because they are right. My role as an artist is not to control the outcome - what I do is my contribution to making sure that these issues are not forgotten."

Climate on the back burner

⦁ Only 2% of global funding for post-COVID-19 reconstruction went to clean energy.

⦁ The world spent $2.4 trillion on military budgets in 2023 compared to $750 billion on climate change adaptation and mitigation.

⦁ UN Secretary-General António Guterres: "We are approaching climate hell with our foot on the accelerator".

The artist as conscience of the planet

Despite all the optimism, Von Wong takes a sober view of the difficulties. His installations are temporary. They require enormous effort to build and even more effort to dismantle. Sometimes they are recycled and sometimes destroyed. The work is exhausting and the funding uncertain. Yet he perseveres towards his goal.

"Because what is the alternative?" he asks. "To look away? To give up? The world is in a difficult moment right now. But that doesn't mean we should stop. We are doing the best we can with what we have."

Art by itself will not save the planet, but according to Von Wong, it doesn't have to. "No single person or sector is going to fix it. But each of us has a role to play. I'm an artist - so I use art to make my contribution. If everyone just did their best in their field, the world would be a better place."

This is not the message of a naive optimist. It is the conviction of someone who has looked at waste, at plastic, at indifference, and decided to transform it into something that cannot be ignored.

Ultimately, Von Wong's art is not about sustainability. It is about memory.

A siren among the bottles. A tap pouring out plastic. A thinker bearing our sins.

These are not just installations. They are monuments to our time - impermanent like the planet itself, but memorable - long after the negotiations are over, after the straws have been recycled, after the installations have been torn down.

They remind us of what we have wasted. But more importantly, of what we still have to lose. And maybe, just maybe, about what we can still save.