A digitisation project that catalogues tape recordings from as early as 1890 is reconnecting Russia with forgotten voices, stories and songs from its Arctic north.

The voice on the recording is scratchy and distant. The fevered chanting of a traditional village shaman in the Russian Arctic recorded decades ago, and now fading into history.

His forgotten voice is one of thousands gathered in the Soviet Union, as ethnographers catalogued the everyday lives, songs, folklore and languages of the peoples across the vast federation.

The collection, currently stored in archives at St. Petersburg’s Pushkin House research institute, is the focus of a new project with the University of Aberdeen in Scotland to digitise and save voices from the Arctic north in particular.

“This archive has tape recordings going back to the very first reel-to-reel tape recordings in the 1930s, right up through the 1970s, from ethnographers all across Russia,” explains Professor David Anderson, an anthropologist at the University of Aberdeen who recently secured $50,000 (€44.329) to fund the two-year digitisation project.

“The original Soviet machines they recorded on no longer work, and the archive no longer has the way to reproduce these sounds,” he says, although some of the recordings made on wax cylinders as far back as the 1890s can still be played on a modern phonograph.

Investing in specialist equipment from Germany will help researchers play the tapes at slow speeds, allowing them to be given a digital ‘audio cleaning’ to take out background distortions, and then save them as MP4 or WAV files.

But the process comes with risks.

“There is a problem that tapes don’t age very well, so for some of the earliest tapes you might get one shot at playing it, and after that, it disintegrates” says Professor Anderson.

Many of the voices on the Russian archive come from communities that no longer exist in their original locations, as people were resettled in bigger cities as part of the Soviet Union’s policies of industrialisation.

“These communities still exist, often in an urban context, but they’ve lost touch with the original villages where these recordings were made.”

During collectivisation, the unique traits of minority languages mixed together to form new types of creole, meaning that while younger people with links to specific areas might not fully understand the languages on the tapes from decades ago, older members of those communities still remember their relatives speaking the original 50 or 60 dialects.

These recordings, says Professor Anderson, provide a rare opportunity to hear legends and folklore in the way they would have been spoken when people still lived on the land, before large-scale Soviet-era resettlement programmes began.

A quest to catalogue the people of the multi-cultural Russian Empire

The earliest examples of ethnographic fieldwork in Russia date back to the days of the Russian Empire in the late 19th century but then continued in Soviet times - although the reasons for undertaking the research were quite different.

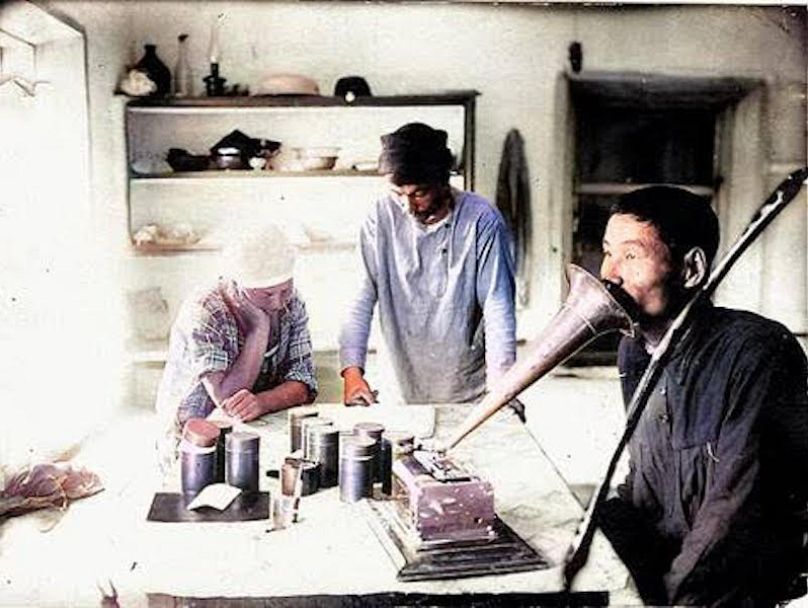

Ethnographers of the Empire would go out to communities to write notes, and sometimes take photographs or make audio recordings as technology improved, as a way of cataloguing and understanding its citizens.

“The Russian Empire had an image of itself of being a multicultural empire, and they wanted to have evidence of all these different groups and their relationship to the Tsar, and how they all fit together in all the nested groups they had within the hierarchy,” says Professor Anderson.

Scientifically at that time, there was a lot of interest in discovering the origins of different ethnic groups, particularly Finno-Ugric people in Western Siberia; while during the Soviet Union there was more of a geopolitical angle to the work of ethnographers, to prove the people in Eastern Siberia had more links to Russia than China.

“It is a bit sinister, but that’s what influenced much of the Soviet ethnographic work. They developed specific linguistic theories like the Ural-Altaic hypothesis which tried to show that all these groups were united in one linguistic root that didn’t extend across the border into China.”

Soviet ethnographers would return year after year, over the course of decades, to speak to the same people and get them to tell particular stories during formal interviews.

Some of the field trips were so thorough that it’s even possible today to go back to individual towns and villages and match up the places and find descendants of the original interviewees.

Future-proofing the archive

At the time recordings were made, on wax cylinders or tapes, the technology was considered cutting-edge in much the same way as making digital recordings today.

So how do anthropologists ensure that these new versions of the Russian voices remain accessible to future generations?

The answer lies in continually updating the archive, says Professor Anderson.

“As far as we’re concerned the MP4 files or the WAV files are the standard that will always be used, but those standards can shift.”

“The only way in any digitisation project to ensure long-term sustainability is to constantly record and re-record. So every ten years you re-record onto a new medium, using a new format, to make sure the materials can always be understood.”

It’s a laborious and ongoing process, but ultimately for historians, for anthropologists, and people from across the communities of Russia’s Arctic north who want to understand their own roots, it’s an invaluable process.

“These recordings are particularly important obviously for the direct descendants who are relatives of these orators, but also for people to know that their culture is important,” Professor Anderson said.

“Even the fact there is a recording of their culture gives a sense of pride.”