Seventy one years ago, on June 6, 1944, thousands of men and women were preparing to take part in an operation that marked the start of the end of World War II. The D-Day landings had been planned for more than a year and involved more than 130,000 allied troops. By the end of the day more than 10,000 people had been killed, injured or taken prisoner. Today it is still the largest seaborne military operation the world has ever seen.

As part of our coverage of the commemoration we have put together a list of some of the most incredible and surprising D-Day facts and photos.

1. The deadly D-Day rehearsal

On April 28, 1944, eight ships full of US servicemen and equipment were making their way to the Devon coast in the UK to take part in a rehearsal for the D-Day landings. Unfortunately, a mistake in their paperwork meant the ships were using different radio frequencies, so when a group of German boats picked up on the heavy radio traffic, the slow-moving US landing ships and their lack of communication proved to be easy targets for the German torpedoes. In total some 800 people were killed in the botched operation, a heavier loss than on some of the D-Day beaches.

Worried about leaked intelligence and a drop in morale, Allied commanders ordered a blackout on all information about the attack and some families never found out how their relatives had died.

euronews streaming LIVE: Coverage of memorial events for the 70th anniversary of D-Day

2. A woman’s charm?

In Jonathan Mayo’s book D-Day he tells the story of Terence Otway, whose unit was tasked with attacking the Merville battery on D-Day. Otway wanted to be sure that his men wouldn’t leak this highly sensitive information in advance, so to test security he send thirty of the prettiest members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, in civilian clothes, down to the local pubs. The women were told to do all they could try and get the information. None of the men fell into the trap.

3. Churchill’s fears

Despite his well-documented capacity for inspirational speeches, on the night before D-Day Winston Churchill was feeling less than confident. He apparently confided his fears to his wife the evening before the landings telling her:

“Do you realise that by the time you wake up in the morning 20,000 men may have been killed?”

4. Code names in the crossword

During D-Day preparations top-secret code names were used to hide the allies’ plans from the enemy. ‘Utah’, ‘Omaha’, ‘Gold’, and ‘Sword’ were beaches on the Normandy coastline, ‘Neptune’ was the code name for the landings, ‘Overlord’ was the ensuing battle for Normandy and a ‘Bigot’ was the code name for someone who had high level security clearance.

Access to this top-level information was kept securely under wraps. However in 1944 authorities became concerned when a number of these apparently secret code names appeared as answers in the Daily Telegraph’s crossword puzzle. In the month before the D-Day attacks, no less than five code names, including ‘Utah’, ‘Omaha’ and ‘Neptune’ were spotted in the puzzle answers. Alarm bells rang at MI5, which suspected someone was trying to pass information to the enemy, although a search of the writer’s home and office turned up nothing.

5. Deception operations

Code names and information blackouts were just the start of the secrecy that cloaked the D-Day operation. The Allied forces fabricated ‘Operation Fortitude’, a deception strategy employed to try and confuse German troops about where and when they would attack. As part of the ruse the Allies leaked faked plans, sent bogus coded messages across the radio and set up diversionary camps.

To add to the illusion, early on D-Day morning “Ruperts” – dummies dressed in paratrooper uniforms complete with boots and helmets – were dropped in Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais. The dummies were equipped with recordings of gunfire, while the real troops supplied additional sound effects to create the illusion of a large scale airborne attack. This operation, code-named “Titanic,” was designed to distract the German military while the main forces landed further to the west.

6. The D in D-Day

Over the years many people have wondered what the ‘D’ in D-Day stands for; some have suggested Disembarkement-Day, Decision-Day and even Death-Day. In reality the D just stands for ‘Day’.

D-Day and H-Hour represent the secret time and day an operation is set to begin, so before and after WWII many other operations had a ‘D-Day’. The day before D-Day was known as ‘D-1’ and the day after as ‘D+1’, meaning that if the day of the operation changed, all the dates in the plans did not have to be changed.

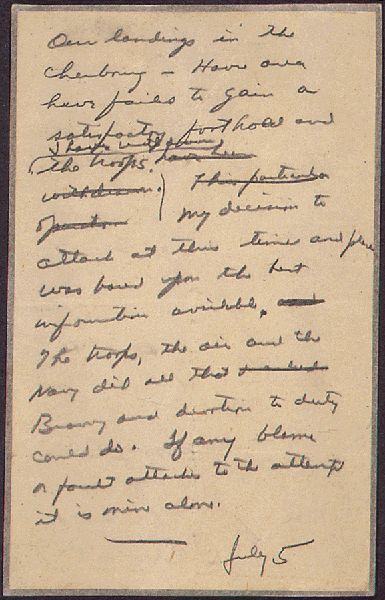

7. Eisenhower’s letter ‘in case the Nazis won’

US General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote a letter that was to be opened ‘in case of failure’. In it he wrote “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

The letter is mistakenly signed July 5 instead of June 5; presumably he was a little preoccupied at the time.

8. Come rain or shine

The original date for the Normandy landings was actually June 5 but as the day approached bad weather forced General Eisenhower to delay by 24 hours. According to the US Navy Department Library, the German military leaders were expecting an Allied invasion in late May when there was a full moon, high tide and little wind. When the weather worsened at the beginning of June the Germans started to relax a little but the Allied forecasters had predicted an opening and the operation was launched.

The Allied meteorologists were hailed for their decision based on this weather map…

At 1pm on this day 70yrs ago, this weather chart was produced. The forecast made based on this was crucial! #DDay70 pic.twitter.com/CHC40dTjVu

— Simon King (@SimonOKing) June 3, 2014

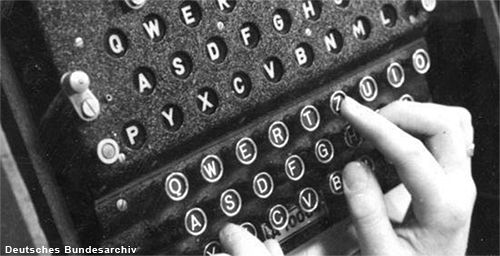

9. Breaking the ENIGMA code

The ENIGMA machine was an encrypting device that the Germans had used since the 1920s. The ingenious machine has more than 200 trillion possible letter combinations and was thought to be unbreakable. However, in the lead up to D-Day, unbeknown to the German Wehrmacht, the Allies had cracked the code with the help of Polish cryptologists. The breakthrough proved invaluable to the D-Day plans because the Allies were able to gather significant intelligence from the decrypted messages. It also allowed them to see if the Germans were buying the deception operations. ### 10. The ‘man who won the war’

General Dwight Eisenhower once said “Andrew Higgins … is the man who won the war for us”. But who is Andrew Higgins?

Higgins is the man who designed and built LCVPs, the amphibious vehicles that enabled the Allied forces to cross the channel. Eisenhower is reported to have said, “If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”