How did life change for workers in the European Union due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic closed or limited many economic activities in 2020, with far-reaching impacts on the labour market.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In order to observe how far the unprecedented health crisis has disrupted workers within the European Union, Eurofound and the European Union Joint Research Centre released a study, named What just happened? COVID-19 lockdowns and change in the labour market.

The report, based on data from Eurostat, describes the employment and working time developments by sector and occupation through the first year of the crisis.

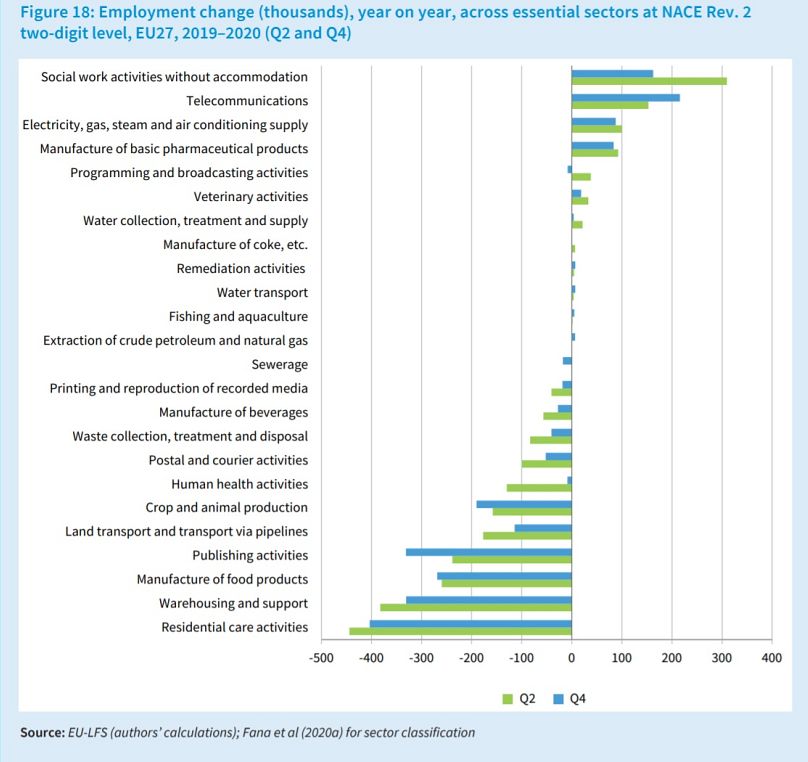

The study found the pandemic has negatively affected work activities that mostly involve human contact and mobility, which were hit hardest by COVID restrictions. These include a wide range of industry sectors, such as the arts, entertainment and leisure to transport, retail and accommodation.

The report explores which categories of workers were most affected – primarily temporary workers, the young and low-paid women. It also assesses the extent to which remote working served as a buffer during the crisis, preserving jobs that might otherwise have been lost.

Five million fewer employees in 2020

In the first quarter of 2020, the EU employment level was already lower than the predicted employment trend, the study noted.

There were about 5.8 million fewer people in employment than what had been predicted by economists in the second quarter of 2020 and about five million fewer employees than in the second quarter of 2019.

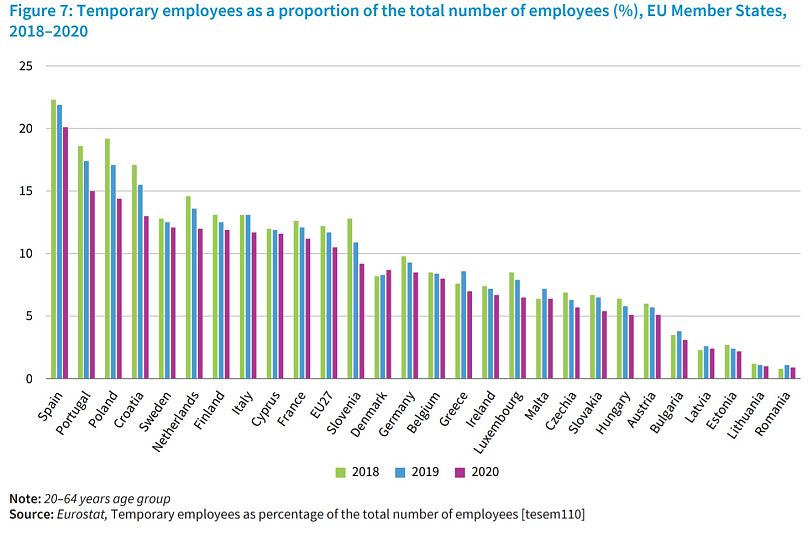

The pandemic has been felt disproportionately by different groups of workers. Workers on temporary contracts accounted for the large majority of employment losses in all quarters of 2020. The recovery in employment levels for this category was muted, while they were less likely to be protected by pandemic support schemes.

Workers on temporary contracts accounted for over three-quarters of net employment losses in all quarters of 2020.

Nearly all Member States in the EU took legislative or regulatory action to contain the virus spread. Deciding whether specific economic activities were essential or had to be closed (or restricted) during the pandemic was the most widely shared.

It was also the blue-collar and production-based occupations that were more affected by the crisis, in particular in its first, more severe, phase during the second quarter (or Q2) of 2020.

The sharpest declines in headcount were among services and sales workers, including retail assistants, restaurant servers, travel- and leisure-related service workers, security and buildings maintenance workers.

These are largely nonteleworkable occupations (jobs that can’t be executed from remote, that require physical manipulation for example) that predominate in sectors that were either closed, essential or mostly essential.

Even sectors identified as essential across the Member States saw working hours drop.

Working remote, the big winner?

Conversely, jobs in knowledge-intensive services grew during the crisis as these sectors rushed to transform or digitalise work processes in response to social distancing measures and higher levels of remote work.

Teleworkable jobs (that can be executed from remote, mostly via a good internet connexion and connected devices, and don’t require the physical manipulation of objects or people) tend to be those with many labour market advantages, less physically arduous working conditions, higher pay and greater job security, the study also highlighted.

Employment in largely teleworkable sectors such as computer programming and consultancy, information services and financial services grew, while many service sectors suffered steep declines in headcount or working hours (or both).

Overall, the share of workers working from home during the pandemic was many times higher than those who did so regularly before the COVID-19 crisis.

These teleworkable jobs have proved more resilient and are characterised by better working conditions and higher wages. EU data sources estimate that at least 21 per cent of workers worked from home at least some of the time in 2020, this is still lower than the overall teleworkable share of employment in the EU, which is estimated at 37 per cent. .

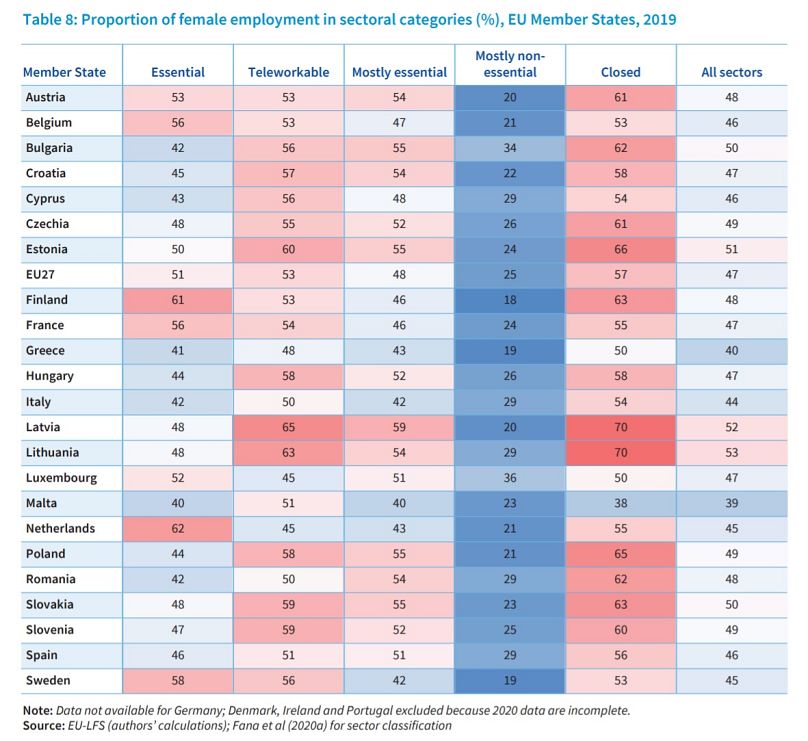

Teleworkable positions are usually held by older workers with higher levels of education, and predominantly by women.

How were women affected?

The survey also asks the following question: “to what extent has this crisis been a ‘shecession’ (or ‘she-recession’), in contrast to the Great Recession?”

While, in the latter, men were more negatively affected owing to their greater presence in production industries, the initial impacts of the pandemic appeared to be worse for women than for men in terms of labour market outcomes.

The most significant relative losses in employment were experienced in female-dominated, contact-intensive sectors such as accommodation and food service activities and administrative and support service activities.

In the accommodation sector, the year-on-year job losses for women approached 20 per cent in both Q2 and Q4, the study flagged.

According to the estimates of Sostero, the share of women in teleworkable occupations in the EU was 45 per cent, compared to 30 per cent for men.

“The gender difference in teleworkability relates, in part, to patterns of sectoral segregation. Men are overrepresented in sectors with limited teleworkability potential such as agriculture, mining, manufacturing, utilities and construction, where tasks involving physical handling are prevalent. However, even in these male-dominated sectors, the teleworkable share of female employment tends to be high.”

Not as bad as expected

In construction, only 6 per cent of male employment is teleworkable, compared to 69% of female employment, for example. Women tend to work in different jobs from men in these sectors and these jobs tend to be the more teleworkable ones: office-based, secretarial or administrative in nature, with a lower share of physical-handling tasks.

In the arts, entertainment and recreation sector, the scale of job losses for men and women varied throughout 2020.

But employment loss among female workers accounted for 35 per cent and 65 per cent of the total drop in mostly non-essential and closed categories, respectively. Yet, “women were underrepresented in essential sectors before the pandemic,” the study highlighted.

“It cannot be concluded that employment composition by gender was a major driver in explaining the patterns of employment change during the first year of the pandemic.”

The 90-page-long survey ends on a rather optimistic note: “A concluding positive message is that the crisis – to date – has not been as destructive of employment or economic activity as was initially feared.”

“European labour markets have shown some resilience to date, notably in suppressing the rise of unemployment. They have been helped by a range of emergency measures designed to cushion the impact of suppressed economic activity on both businesses and individual workers and households.”

The study added that with a widely spread vaccination campaign, the labour market can start breathing back again.