Tens of thousands of ethnic-Albanians, Serbs and other minorities disappeared during the 1998-99 war in Kosovo. Two decades later, thousands are still unaccounted for.

Twenty-three years ago this June, Miroljub Ađančić’s brother was working at the Belaćevac mine near Obilic, not far from Priština, when uniformed men wearing the insignia of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) came and took him and nine of his colleagues hostage.

It was June 22, 1998, the first day of the so-called Battle of Belaćevac Mine during the Kosovo War between the KLA and the forces of Slobodan Milosevic’s Yugoslavia.

The KLA had seized the facility, which provided most of Kosovo’s electricity. A week later, the mine was retaken by units of the Yugoslav Army and Serbian police, which killed ten KLA fighters.

But no trace of the hostages was ever found.

Ađančić has spent the intervening two decades wondering what became of his brother, Zoran, then 30 years old and a crane operator. He believes that he was moved to a KLA camp in northern Albania, where he was killed. But despite reporting the case to the Serbian and Kosovar authorities and international observers in Kosovo after the war, he has heard nothing.

“It all was to no avail. No one cared,” he told Euronews.

More than 3,000 ethnic Albanians were victims of enforced disappearances by Serbian police, paramilitary and military forces during the war in Kosovo, with at least 800 Serbs, Roma and other ethnic minorities in the territory abducted during and after the war, allegedly by the KLA.

Amnesty International found that in April 2009, ten years after the war, around half of the bodies of those who disappeared in the conflict had been found and returned to their families. Just under 2,000 remained unaccounted for. But even in the cases where bodies had been returned, most families said that there had been no investigation into the deaths of their loved ones.

In the small towns and cities and close-knit communities of northern Kosovo, the bereaved have often had to accept that neighbours were involved in the deaths of their family members. Worse still, they have had to watch as the perpetrators go about their lives with impunity.

Silvana Marinković, 49, told Euronews that her husband was kidnapped on June 19 in the village of Labjane, between Priština and Gnjilane, by Albanian soldiers. They were first detained in a school in Mramor, and then taken to the prison in Zlaš, east of the capital, Pristina. One of the men who took her husband is now a police officer, and the other a mechanic.

“I definitely know the names and surnames of the people who took my husband,” said Marinković.

In the years since, Marinković has given statements to UN investigators, as well as those from the various courts established to probe violence committed by both sides during the conflict, from 1999 up to the present day. She said she has given the same information, time and time again, and not a single indictment has been brought based on what she has told them.

“I don't believe in justice anymore. It's been a long time, more than 20 years. [There are] no more witnesses, some died, some were killed, some are afraid,” she said.

“Based on everything that's happened so far, my opinion is that there's only God's punishment.”

The disappeared

The fate of the disappeared of northern Kosovo has been brought to the fore again with the indictment of four former Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) members by the Kosovo Specialist Chambers, a war crimes court based in the Hague and focusing on the conflict between the Yugoslav army and Serb militias and the KLA between 1998 and 1999.

The indicted include the former president of Kosovo and political leader of the KLA in 1999, Hashim Thaci, who stood down as president in November when the indictment was confirmed. Indicted along with Thaci is the former speaker of the Kosovan parliament, Kadri Veseli. Both men deny the charges against them and have submitted to the Hague for trial.

In a report compiled just weeks after the end of the war, the Organisation for Stability and Cohesion in Europe (OSCE) documented human rights and humanitarian law violations on a “staggering scale”. It cited an intent on the part of Serbian and Yugoslav forces to “apply mass killing as an instrument of terror, coercion against Kosovo Albanians.”

By the end of the war in June 1999, the OSCE estimated that over 90 per cent of the Kosovo Albanian population - over 1.45 million people - had been displaced by the conflict, many forced over the borders with Albania and what today is North Macedonia. It was footage of these desperate people and their stories of violence, that first brought Kosovo to the attention of the world.

In the wake of the conflict, Yugoslavia’s president, Slobodan Milosevic, was indicted for crimes against humanity along with seven other Serbian senior political and military figures. Milosevic died in 2006 while awaiting trial at the Hague but six of the seven other Serb defendants were convicted and sentenced to between 15 and 27 years in jail.

But it was not only Serbian political and military leaders that faced indictments from international courts over their conduct during the conflict. As the Yugoslav army and Serbian militias retreated from Kosovo in the face of NATO bombing, the KLA advanced, seizing territory that had been held by Yugoslav and Serbian authorities.

Both international investigators and rights groups alleged that the KLA was responsible for the abduction and murder of Serbs and ethnic Albanians in Kosovo during 1998, and as the tide of the war turned in its favour during the summer of 1999 these abuses worsened.

“The desire for revenge provides a partial explanation, but there is also a clear political goal in many of these attacks: the removal from Kosovo of non-ethnic Albanians in order to better justify an independent state,” Human Rights Watch reported in 2001.

In the years following the war, the ICTY indicted a number of former KLA leaders for war crimes, some of whom had risen to senior positions within the government of Kosovo.

In 2005, after he had served as prime minister for just 100 days, the KLA’s former commander for Western Kosovo, Ramush Haradinaj, was indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), stepped down and delivered himself to the Hague.

Haradinaj was found not guilty in 2008, tried again in 2011, and once again acquitted. In 2017, he was elected prime minister again but forced to resign when he was summoned for questioning by a war crimes court in the Hague. In 2020, Haradinaj announced on Facebook that he was considering a run for president when the position becomes vacant in April 2021.

The root of the modern history of Kosovo lies in the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in south-eastern Europe in the early 20th century, which led to a clash of national identities in the Balkans. Serbs see Kosovo as the cradle of Serbian civilisation, and the site of one of the defining battles between the medieval Serbian ruler Prince Lazar and the Ottomans in 1389.

Ever since, Kosovo has been a rallying cry for Serb nationalists, despite the fact that the territory is - and always has been - overwhelmingly populated by Albanians. Religion also plays a role: Peje, or Pec, in western Kosovo was the seat of the Serbian patriarch and to this day the territory contains some of the Serbian Orthodox Church’s most sacred sites.

Serbia took control of Kosovo in 1912, but after the Second World War Kosovo - like the rest of the Balkans - was subsumed into the state of Yugoslavia. Albanians were recognised as a national minority, but Kosovo was not one of the six republics of federal Yugoslavia and was ultimately considered part of Serbia.

That began to change in the 1970s as Yugoslav leader Marshall Tito became increasingly concerned about Serbia, which with nine million inhabitants was by far the largest of the six republics, dominating the Yugoslav Republic. As a result, Kosovo, which was 90% Albanian, and Vojvodina, which had 4000,000 Hungarians, were given widespread autonomy in 1974.

Tito’s death in 1980 was the beginning of the end of Kosovo’s path towards autonomy in federal Yugoslavia. Noel Malcolm, in his seminal book Kosovo: A Short History, describes how the Albanian Kosovan independence movement burst into the open in 1981 with a protest in Pristina that started after a student in the university canteen found a cockroach in his soup.

Within a fortnight the protests had spread to six cities, with workers joining students on the streets chanting: ‘Kosovo - Republic!’ and ‘We are Albanians - not Yugoslavs’. Security forces were called in from elsewhere in Yugoslavia and a state of emergency was declared. More than 2,000 were arrested and 500 received prison sentences of between one month and 15 years.

The growing independence movement came alongside a rising nationalism in Serbia, and a desire within some quarters to reverse the 1974 decision to grant autonomy to Kosovo. It also came alongside the rise of Milosevic.

It was in the town of Kosovo Polje, the site of Prince Lazar’s battle against the Ottomans in 1389, in June 1987 that the young Milosevic first rose to prominence, inciting a riot with a fiery speech in defence of Serb rights. As the authorities attempted to break up a crowd of Serbs that had gathered for the speech, Milosevic egged on his supporters to take on the police.

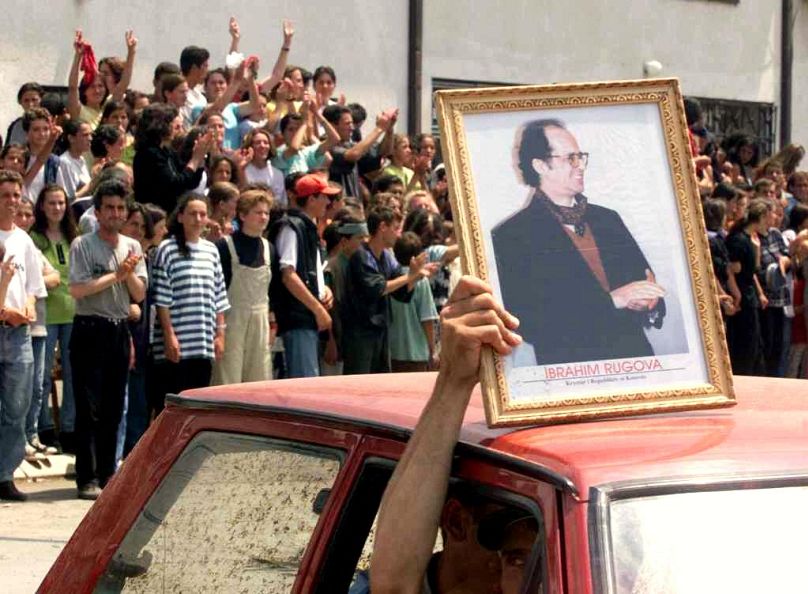

Once he was elected president of Yugoslavia in 1990, Milosevic oversaw an erosion of rights for Kosovo’s Albanians in the first half of the decade, including restrictions on the Albanian language. It was these reforms and the failure of the peaceful pro-Albanian movement of future president Ibrahim Rugova which led to the foundation of the militant KLA in the mid-1990s.

Enclaves

When NATO’s 78-day bombing campaign between March and June 1999 forced the Yugoslav army and Serb paramilitaries across the border into southern Serbia, tens of thousands of Serbs fled with them, and to this day represent the largest proportion of displaced people in the country. In the years since Kosovo’s declaration of independence, this exodus has only continued.

Nowadays, there are around 120,000 Serbs living in Kosovo, most of them in villages in the north of the country as well as some enclaves in the south-east. Goran Koprivica, a journalist who lived and worked in Kosovo during the conflict, is one of those who left in 1999, and still remembers the harrowing journey made by so many as the conflict raged around them.

“I think of these people, the poor wretched people from those villages, in some old Yugo cars, loaded with things and bedding, the cars break[ing] down,” he told Euronews.

“I thought I was going to come back, I just had one tracksuit on me and nothing else. I try to explain to people what it's like to move somewhere even in an ideal situation, moving from one city to another and everything waiting for you, an apartment, a job. Would it be easy for you? No. Let alone in our conditions, going from Kosovo to who knows where.”

Hundreds of thousands of Kosovars, of course, were forced to make similar journeys in the other direction during 1998 and 1999, tens of thousands were killed and many remain unaccounted for. But two decades on, for Koprivica, the lack of justice and of a solution for Kosovo and Serbia that would satisfy both parties remains remote.

“In this whole story, no one is a winner,” he said. “We are all losers, both Serbs and Albanians.”

Every weekday at 1900 CET, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get an alert for this and other breaking news. It's available on Apple and Android devices.