Devices like pacemakers have kept millions alive. But injectable wireless chips the size of a grain of salt could eventually replace these lifesaving devices.

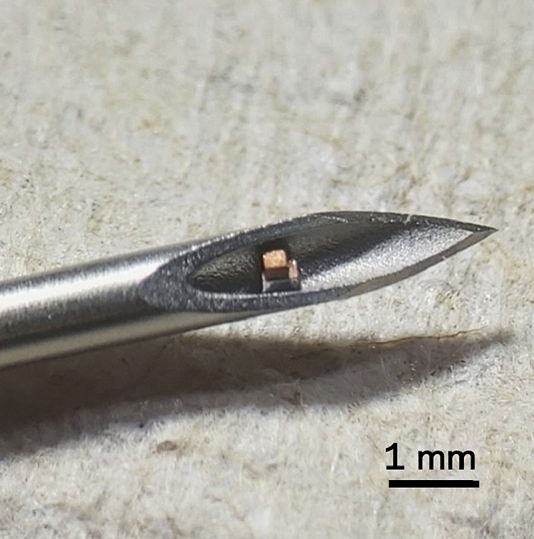

Only visible using a microscope, an injectable chip the size of a grain of salt could transform the electrical devices we implant into people to keep them alive.

At just 0.1 mm3 in volume, which is roughly comparable to a dust mite, scientific researchers at Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science believe they have developed the smallest single-chip system in the world.

Implantable devices have long proven their worth in treating diseases, improving the function of organs and body parts as well as monitoring long-term conditions.

Some of the most widely-used devices - such as pacemakers and cochlear implants - have vastly improved people’s quality of life and saved countless patients' lives.

For the most part, though, they are unwieldy, needing multiple circuits, wires and battery packs. They also require surgery to put them inside the body.

But could this chip mean larger implantable devices like these are a thing of the past?

Pushing the limits

Producing wireless, miniature devices has increasingly become the focus of teams like that of Columbia University.

"We are very interested in implantable devices we call 'chip-as-system' (CaS) devices, of which the chip developed in this study is one example," Ken Shepard, the study's leader and a professor of biomedical engineering, told Euronews.

"These are implantables in which the entire implantable is a single integrated circuit. The metric here is volumetric efficiency - the amount of function that can be squeezed into a given amount of displaced volume.

"We wanted to see how far we could push the limits on how small a functioning chip we could make".

In order to achieve this, the team relies on ultrasound to find and communicate with the chip wirelessly in order to relay information back about the area of the body it is injected into.

Ultimately, it’s believed devices like the one produced in this study could be used initially to monitor temperature, blood pressure, glucose levels, and respiration.

'CaS devices are the future'

"Our focus for these devices moving forward is actually wound healing, giving them many diverse sensing capabilities that can be reported back through an ultrasound image," Shepard told Euronews.

As well as increasing functionality in a smaller device, the team’s goal was to develop a chip that could be administered using a hypodermic needle to inject it into the body rather than needing to use surgery.

While the chip currently only measures body temperature, the team see the study as a stepping stone for future advancements of implantable CaS devices.

"CaS devices have three main characteristics," said Shepard.

"They have to have wireless powering and data (no wires or batteries); they have to integrate whatever additional transducers may be required (for the devices in this study, these are piezoelectric crystals); and the chips themselves have to be shaped into an implantable form factor (in this study, this is the ultra-small injectable but other form factors are possible depending on the application)," he added.

"In my honest opinion, CaS devices are the future of implantables for all kinds of applications".