But environmental activists say the country's Cerrado savannah has become a ‘sacrificed biome’.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon rainforest slowed by nearly half compared to the year before, according to government satellite data released on Wednesday.

It’s the largest reduction since 2016, when officials began using the current method of measurement.

In the past 12 months, the Amazon rainforest lost 4,300 square kilometres, an area roughly three times the size of London. That's a nearly 46 per cent decrease compared to the previous period. Brazil’s deforestation surveillance year runs from 1 August to 30 July.

Still, much remains to be done to end the destruction and the month of July showed a 33 per cent increase in tree cutting over July 2023.

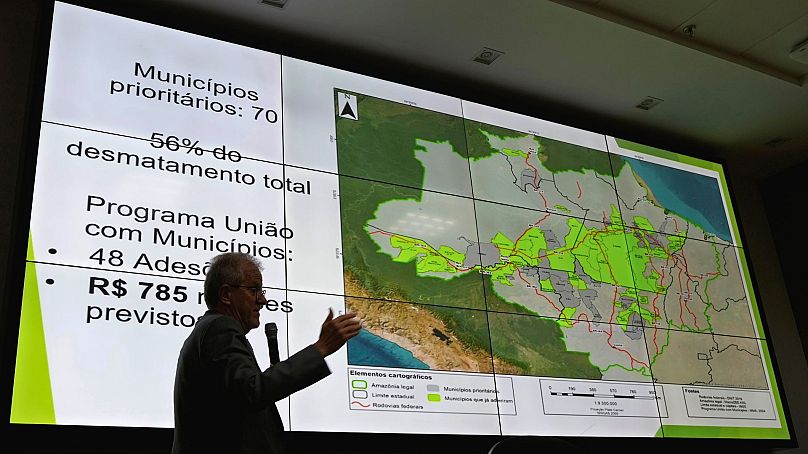

A strike by officials at federal environmental agencies contributed to this surge, said João Paulo Capobianco, executive secretary for the Environment Ministry, during a press conference in Brasília.

The figures are preliminary and come from the Deter satellite system, managed by the National Institute for Space Research and used by environmental law enforcement agencies to detect deforestation in real time. The most accurate deforestation calculations are usually released in November.

Amazon protections aren't extended to Brazil's savannah

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has pledged 'deforestation zero' by 2030. His current term ends in January 2027. Amazon deforestation has steeply declined since the end of far-right President Jair Bolsolonaro's rule in 2022. Under that government, forest loss reached a 15-year high.

About two-thirds of the Amazon lies within Brazil. It remains the world’s largest rainforest, covering an area twice the size of India. The Amazon absorbs large amounts of carbon dioxide, preventing the climate from warming even faster than it would otherwise. It also holds about 20 per cent of the world’s fresh water, and biodiversity that scientists have not yet come close to understanding, including at least 16,000 tree species.

During this same period, deforestation in Brazil's vast savannah, known as the Cerrado, increased by 9 per cent. The native vegetation loss reached 7,015 square kilometres - an area 63 per cent larger than the destruction in the Amazon.

The Cerrado is the world’s most biodiverse savannah, but less of it enjoys protected status than the rainforest to its north. Brazil's boom in soybeans, the country’s second-largest export, have largely come from privately-owned areas in the Cerrado.

“The Cerrado has become a ‘sacrificed biome’. Its topography lends itself to mechanised, large-scale commodity production,” says Isabel Figueiredo, a spokesperson with the nonprofit Society, Population and Nature Institute.

Both Brazilians and the international community are more concerned about forests than savanna and open landscapes, she says, even though these ecosystems are also extremely biodiverse and essential for climate balance.

How can Brazil control deforestation?

To control deforestation in the long term, monitoring, such as with satellites, and law enforcement are not enough, says Paulo Barreto, a researcher with the nonprofit Amazon Institute of People and the Environment.

New protected areas are needed, both within and outside Indigenous territory, as well as more transparency so that slaughterhouses track where their cattle are coming from.

Cattle ranching is the leading driver of deforestation in the Amazon. Degraded pasture lands also need to be replanted as forest, Barreto says, and there must be stricter rules for the financial sector to prevent the funding of deforestation.

Interviewed in Brasilia, Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva conceded that so far, law enforcement has been the main tool against deforestation, but government action must and will be broader.

“From now on, we need to combine continued law enforcement with support for sustainable productive activities, which is one of the pillars of our plan."