Europe is warming almost twice as fast as the global average, at about 2.2C above pre-industrial times.

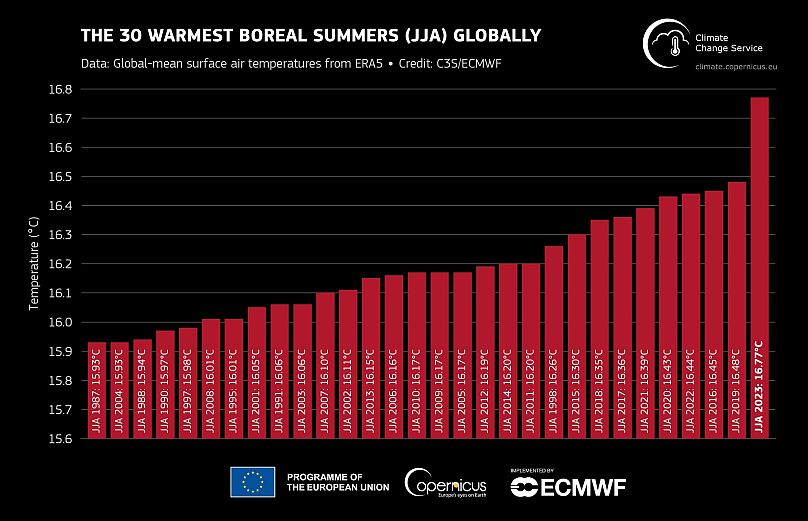

Scientists confirmed this week that summer 2023 was the hottest season the world has ever seen by a large margin.

“It's hugely pronounced on the graph, and it makes me really nervous for what's to come,” says Dr Samantha Burgess, deputy director of the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

The boreal (northern hemisphere) summer June-July-August leapt to an average temperature of 16.77C - 0.66°C above the average for this time of year.

“This is one of the challenges that we face as a climate scientist,” she explains. The new record isn’t out of line with what scientists had predicted for this period - albeit on the “outer edge” of that range.

But, she adds, “What makes me nervous is the dynamics that we can see in the system.”

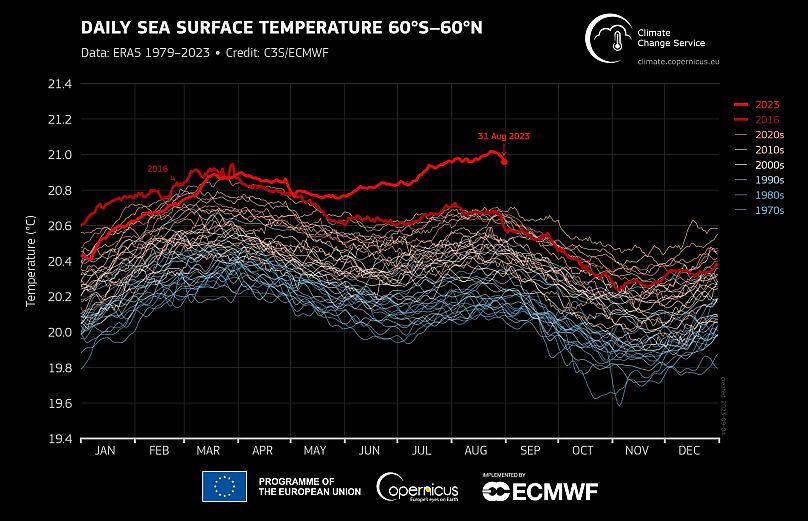

For starters, the ocean has never been this warm. “If I look at the graph of ocean heat, I'm wondering where it's going to go, because we're not at the time of year where it should be at maximum,” she says.

Secondly, we’re in an El Niño year, which has a warming impact on global temperatures.

“We also know that each El Niño is different and that no other El Niño has ever started with an ocean this warm. So we don't know yet how strong an event it’s going to be, and we're watching very carefully over the next few months.”

2023 is on track to not only break records for the hottest summer, but to be the hottest year the world has ever seen. Currently, it’s 0.01 degrees behind 2016 for the same period, explains Dr Burgess.

“With that heat in the global ocean, 2023 - unless we have a crazy cold winter and autumn - 2023 will be the warmest year we've ever had,” she tells Euronews Green.

But, this ‘hottest summer of our life’ could be remembered as one of the coldest if emissions are not urgently reigned in.

“With that El Niño developing, 2024 is likely to be the warmest still,” says Dr Burgess.

Global heating is ushering in more extreme events, as just one European country’s summer shows. Greece has suffered fire and floods in quick succession; earlier this week, one region received almost double its average annual rainfall over two days.

Researchers have found that each degree Celsius the atmosphere heats increases the amount of water vapour it can hold by 7 per cent.

Europe is warming faster than the global average

When we talk about preventing runaway climate change by limiting global heating to 1.5C - as per the Paris Agreement - it’s the global average that counts. Currently, the world is running at around 1.2C above pre-industrial levels and, as Dr Burgess says, “every fraction of a degree matters”.

Europe is warming faster than the global average, at about 2.2C above pre-industrial times (circa 1850-1900). The continent’s average temperature this summer was 19.63C, 0.83C above average, making it the fifth warmest for the summer season.

Our proximity to the Arctic - which is warming at about 3-4 times the global average - partly explains this difference. Sea ice loss around the North Pole affects the region’s albedo (its ability to reflect sunlight) with feedback impacts for Europe too. But there’s a huge number of reasons behind global variations in temperature rise.

What is the difference between ground and air temperature?

The Paris Agreement's goal of keeping global heating to 1.5C (and well below 2C) refers to global air temperature.

This ‘near surface air temperature’ is recorded at two metres above the ground, under strict instructions from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

It gives a cooler reading than ground temperature since the ground absorbs much more radiation. The land is also warming up faster than the ocean.

Between 2013 and 2022, European land temperatures increased by around 2.04 to 2.10°C, according to the European Environment Agency (EEA).

How does European warming vary between countries?

Global heating at a country level varies across Europe too. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) recently released statistics on temperature change on land, which allow us to compare trends between European countries.

The baseline here is different, as the statistics measure temperature change in relation to the 1951-1980 average, not pre-industrial times.

In 2022, the global annual temperature on land was 1.39°C warmer than the 1951-1980 average. Europe saw the largest temperature rise (2.23°C) of all the continents last year.

In 22 out of 41 European countries included in the data, temperatures rose by over 2°C. In terms of air temperature, summer 2022 was Europe’s hottest on record, driven by a significant number of heatwaves.

France recorded the highest land temperature rise in 2022

In 2022, the annual temperature change on land compared to the 1951-1980 baseline varied from 1.04°C in Greece to 2.93°C in France and Luxembourg.

Belgium, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany also saw land temperature rises greater than 2.5°C.

Why is there so much temperature variation over the years?

Natural variability in the system means that the size of the annual temperature change varies every year in each country.

While the land temperature rise was 2.26°C in the EU in 2022, it was just 1.54°C in 2021. France was below the EU average in 2021, whereas it experienced the highest rise in 2022.

But the long-term trend is very clear.

Temperatures have been rising for 38 consecutive years in Italy

The number of consecutive years in which the temperature on land was higher than the 1951-1980 average has been increasing in each country. That is concerning for climate scientists.

By 2022, it varied from 12 years in the UK, Sweden, Norway, Ireland and Denmark to 38 years in Italy and Malta.

Most countries had their last annual temperature decline either in 1996 or 1997. Land temperature has been rising in all 41 selected European countries since 2011.

In 2022, Europe experienced its sixth year in the past decade with rises in land warming above 2°C on average.

Highest rises and falls in annual land temperatures in Europe

Looking at the changes in the last four decades, the annual land temperature rise exceeded 3°C in seven countries. This mostly happened in Eastern European countries in 2020 when a major heatwave scorched the continent.

Russia saw the highest temperature change of 3.69°C, followed by Estonia (3.63°C) and Latvia (3.55°C).

‘The era of global boiling has arrived’: When will 1.5C be breached?

July 2023 was 1.5°C warmer than the pre-industrial average according to the C3S. Based on this data, UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated that “the era of global warming has ended” and “the era of global boiling has arrived.”

Though the 1.5C global threshold has been temporarily breached, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) makes clear in its latest assessment report that a meaningful breach will be measured in years, not months.

Climate models indicate we’re likely to hit 1.5C for an entire year in the early 2030s. It will take around 20 years after that before scientists can confidently say we’ve blown our chances of limiting global heating to this critical threshold.

This will be because greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere have risen to such an extent that we’ve now got a blanket of greenhouse gases around the Earth that’s keeping that heat trapped in, says Dr Burgess.

“The sooner decision makers around the world realise that they need to step up and take action to mitigate future impacts, the better the planet will be not only for people in our generation, but for the generations to come.”

The FAO’s statistics are based on the publicly available Global Surface Temperature Change data distributed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (NASA-GISS).