In honour of World Turtle Day we look back at one of our favourite good news stories of the year so far.

Not a single green turtle egg could be found on Reunion Island 20 years ago.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Three centuries of human settlement on the small French island in the Indian Ocean were enough to eradicate baby turtles from the beaches until 2004.

But years of conservation work have once again made the French overseas department a hospitable place for the globally endangered species.

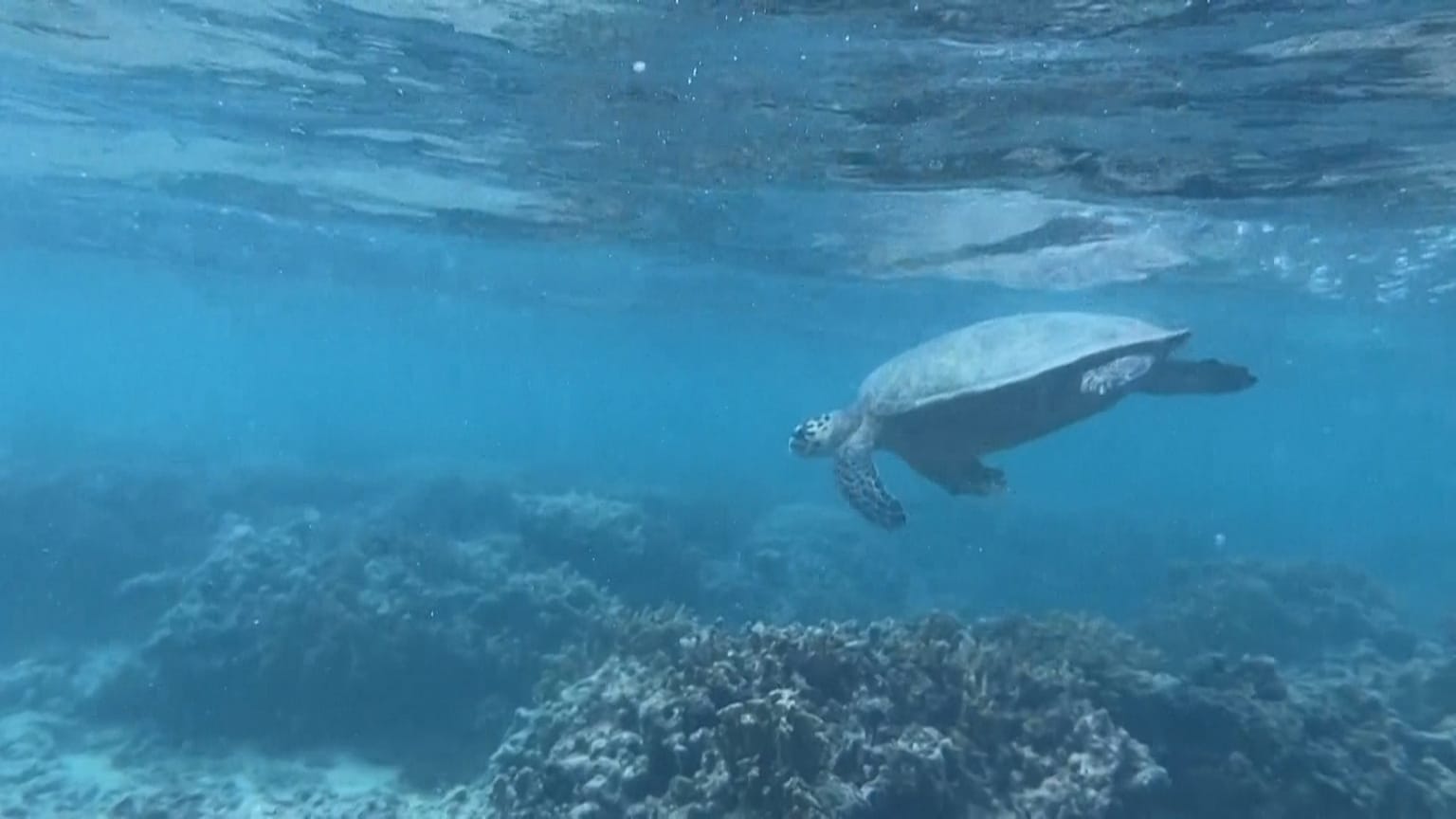

More and more young turtles, both green and hawksbill, are making their return to Reunion lagoon, in the heart of a protected marine reserve.

If this flourishing biodiversity had a poster girl it would be 30-year-old Emma; one of two reproductive turtles in Reunion, and the most reliable.

The 150kg green turtle gave birth to her sixth round of eggs earlier this year. They take 52 days to incubate and then a month and a half to hatch.

Why have turtles returned to Reunion Island?

Juvenile turtles first come to the lagoon to feed, explains Rachel David, an intern at the Kélonia Sea Turtle Observatory on Reunion.

Once they become adults, the marine animals swim further away to feed in deeper water, before returning to the beach they were born on to reproduce. The females will lay their eggs near these beaches.

Green turtles take 20 - 30 years to reach full maturity and start laying eggs.

“This is the case, for example, of the turtle Emma, which comes to lay eggs on a beach in the west of Reunion Island, a beach that remains secret, obviously, to protect Emma and her future children,” she says.

The last eggs known on the island were in 2004. The staff at the observatory are hopeful that more of those turtles have survived and will also return to lay eggs.

Though the Kélonia sea turtle observatory, opened in 2006, is trying to give the herbivorous creatures a fighting chance, there are still plenty of obstacles in a green turtle’s life.

Emma herself was hit by a boat travelling too fast, escaping with a missing piece of rib and shell bone above her kidneys. It could have been a fatal wound.

“It's true that the chances of survival are between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1,000,” says Stéphane Ciccione, director of the observatory.

“But these survival rates have existed for 110 million years and the turtles have not disappeared, so this is not the cause of the reduction in turtle populations.”

Focusing on the anthropogenic causes of mortality is a more worthwhile mission for conservationists. The threat of being poached for their meat, shell and eggs is now overshadowed by plastics, boats and urbanisation.

“And on the other hand, for the predation of young turtles, we leave it to nature, in any case, nature always does better than us, so we leave it to it and trust it,” concludes Ciccione.

Watch the video above to see Reunion’s baby turtles.