Eunice Foote discovered the effects of global warming in 1856, but didn't get the credit she deserved.

Chances are you’ve never heard of Eunice Foote, but she was the first person to document climate change. Five years before the man credited for discovering it.

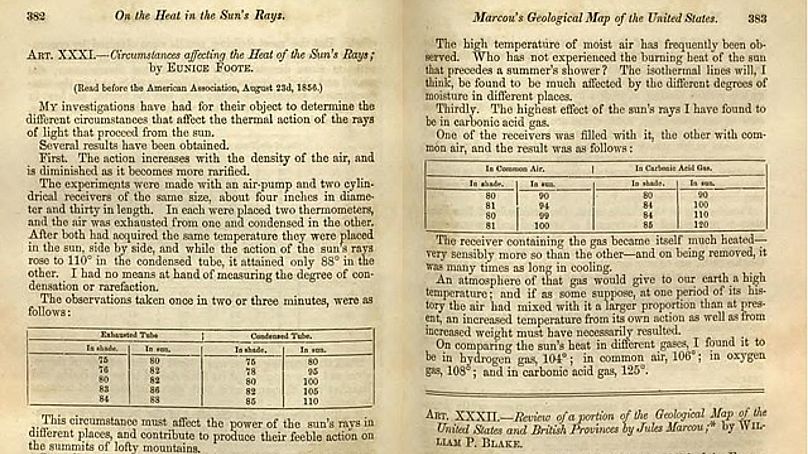

Foote’s experiment, which was documented in a brief scientific paper in 1856 noted that “the highest effect of the sun’s rays, I have found to be in carbonic acid gas [carbon dioxide].”

This discovery laid the groundwork for the modern understanding of the ‘greenhouse gas effect’ but the recognition was given to an Irish scientist named John Tyndall in 1861.

Who was Eunice Foote?

Eunice Foote was 37 years old when she made her climate breakthrough. Brought up on a farm in Connecticut, US, in her late teens she attended the Troy Female Seminary (later the Emma Willard School) - the first women’s prep school in America.

Based in Troy, New York, it was the first school to offer young women an education that was comparable to a man’s, with subjects including advanced maths and science.

One of her teachers was Amos Eaton, who co-founded the nearby Rensselaer School for boys and changed the way that science was taught in America.

It may have also helped that her father shared a name with one of the founding fathers of science - Isaac Newton.

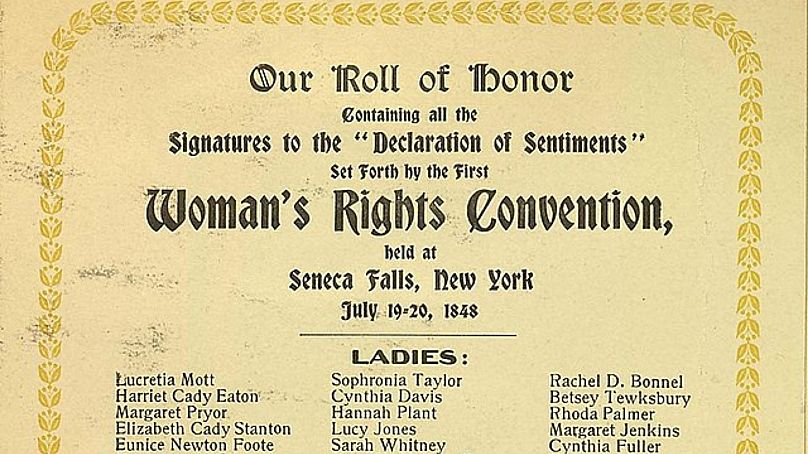

Alongside her interest in science, Foote was also an active women’s rights advocate and was on the editorial board of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first woman's rights conference, organised by prominent suffragist Elizabeth Candy Stanton.

How did she discover climate change?

Foote’s scientific paper ‘On the heat in the sun’s rays’ was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts in November 1856.

The experiment that she conducted involved two glass cylinders, two thermometers and an air pump. She pumped carbon dioxide into one of the cylinders and air into the other, and then placed them out in the sun.

“The receiver containing the gas became itself much heated - very sensibly more so than the other - and on being removed, it was many times as long in cooling,” she says in her paper.

The higher temperature in the carbon dioxide cylinder showed Foote that carbon dioxide traps the most heat. She performed the experiment on a range of different gases including hydrogen and oxygen.

“On comparing the sun’s heat in different gases, I found it to be in hydrogen gas, 108°; in common air, 106°; in oxygen gas, 108°; and in carbonic acid gas, 125°.”

This finding led Foote to conclude that, “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from increased weight must have necessarily resulted.”

This was the first scientific acknowledgement that CO2 had the power to change the temperature of the Earth.

Why did John Tyndall get the credit?

John Tyndall was an Irish physicist, who was already well known within the scientific community for his work on magnetism and polarity when Foote published her findings.

In fact, Tyndall had published a paper on colour blindness in the same edition of The American Journal of Science and Arts as Foote had published her carbon dioxide experiment.

Then in 1861, John Tyndall demonstrated the absorptive nature of gases, including oxygen, water vapour and carbon dioxide. Using a ratio spectrophotometer of his own design, he measured the infrared absorption of these gases in what would later become known as the ‘greenhouse effect’.

There is some debate as to whether Tyndall stole Foote’s research, though perhaps it is fairer to say that reading it influenced his future discoveries - though he did not reference her in his findings.

Either way, the result is the same - Tyndall was commemorated as one of the founding fathers of climate change science, while Foote was forgotten until the early 21st century.

Tyndall remained a prominent scientist until his wife accidentally killed him in 1893 by giving him a fatal dose of chloral hydrate, which he took to treat his insomnia.

What was early climate science like?

The 19th century was a key turning point in climate science and the use of fossil fuels. In 1800 the world population reached one billion for the first time and the industrial revolution began to take hold - fuelled by the development of James Watt’s steam engine in the late 18th century.

By the 1880s, coal was being used to generate electricity for factories, while the first automobile, Karl Benz’s ‘Motorwagen’ heralded the age of mass private transport.

By 1927, carbon emissions from fossil fuels and industry hit one billion tonnes per year. Just for context, in 2019 fossil fuel use hit 36.7 billion tonnes.

These massive societal changes were not fully understood at first, and Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius believed in 1896 that the greenhouse effect and subsequent temperature rise from burning coal - which he correctly predicted would be a few degrees - might actually be beneficial for humanity.

In fact, the greenhouse effect and its cataclysmic consequences wouldn’t begin to be taken seriously until the mid 20th century, after US scientist Wallace Broecker coined the term 'global warming'.

Other scientific women who have been forgotten

Foote’s contribution to the history of climate science was finally rediscovered in 2010 by Ray Sorenson, a retired geologist. He published his discovery and in 2019 the University of California in Santa Barbara put on an exhibition about Foote’s work.

Unfortunately, Foote isn’t the only female scientist to be written out of history or have their discoveries credited to a man. Lise Meitner, a key member of the scientific team that discovered nuclear fission was overlooked for a Nobel Prize, which was given to her co-scientist Otto Hahn.

Thankfully though, women are beginning to get the recognition they deserve, as films like ‘Hidden Figures’, which tells the story of NASA mathematicians - Katherine G. Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson - show.

The three women of colour played key roles in the early years of NASA, but were historically overlooked until the film’s release in 2016.