Millions of weapons were dumped in the sea after WWII and the 100-year work of removing them is just beginning.

The story of sea-dumped chemical weapons might seem a tragic one but there is finally hope that this toxic waste could soon be removed.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Huge amounts of munitions were dumped in the ocean in the early twentieth century following the two world wars. The Baltic Sea alone is estimated to hold 1.6 million tonnes of munitions - enough to stretch from Paris to Moscow if loaded on a train.

The impact on marine life is worsening as their casings degrade. For humans embarking on more and more off-shore developments, the situation is reaching a critical point.

But for legal expert and environmentalist Grant Dawson, it is precisely this urgency that is promising. The narrative around underwater weapons is starting to change.

The former UN Legal Officer was delighted to see politicians showing up for the first time at an international conference in Kiel, Germany last month. Those interested in the fate of the dumped weapons included the Minister-President of Schleswig-Holstein, a state bordering the Baltic, and the leader of the German Navy.

“It’s very exciting because everyone was having a very polite argument about which site do we start first, and they were saying ‘well there are more tourists here, but there’s more fishing here.’”

This year, the European Parliament issued a resolution requesting the European Commission to start removing these weapons from the Baltic Sea.

The pivot from researching the issue to exploring solutions has come recently, explains Mr Dawson, who is completing a PhD on the subject and writing a sci-fi novel with the evocative title ‘The Lost Trident of Poseidon’.

Retrieving the munitions marks the start of a 100-year project that “hooks into climate change both psychologically and sociologically”.

As with global warming, the submerged munitions problem is not something we will correct in our lifetimes, but intergenerational equity - an important legal principle - demands we start now.

What impact is chemical waste having on the environment?

As environmental consciousness picked up in the 60s and 70s, hazardous sea dumping was effectively outlawed by the London Convention of 1972. But that doesn’t mean weapons that were dumped in the past aren’t still having an impact on the environment now.

As well as being a ticking time bomb for future generations, old underwater weapons are having a lethal effect on marine life.

These aren’t just chemical toxic weapons either, but conventional weapons that have corroded and turned toxic over time (like the explosive TNT), and nuclear waste.

Scientists sampling the tissues of animals around the sites have found them to be contaminated with toxins, which can kill them and reduce their birth rates.

Off the coast of LA, a huge amount of industrial waste including the pesticide DDT has caused 25 per cent of sea lions to develop aggressive cancer.

“We have dumped our toxic garbage into someone else’s backyard, and whose backyard is that?” says Mr Dawson.

“It’s not just ours in a very indirect way; there’s whales, there’s sea lions, there’s dolphins, there’s starfish, there’s fish, there’s microbes... and it’s just not right.”

How to solve the problem of Poseidon’s lost trident

When ships were ordered to abandon armaments at sea, many did not travel as far off the coast as they were supposed to. Millions of poorly documented munitions now sit on our continental shelf.

“Some people honestly thought back then, in the beginning of the twentieth century, that the ocean was this inexhaustible place where you could dump anything,” says Mr Dawson.

North.io is one of the companies hoping tech can find a solution to the problem. It is using AI to search through 50 kilometres of archival documents.

This information sends the trackers in the right direction, but human error comes into it too. The sensors often pick up lines of munitions closer to the shore, where they were dumped overboard by time-saving German fishermen.

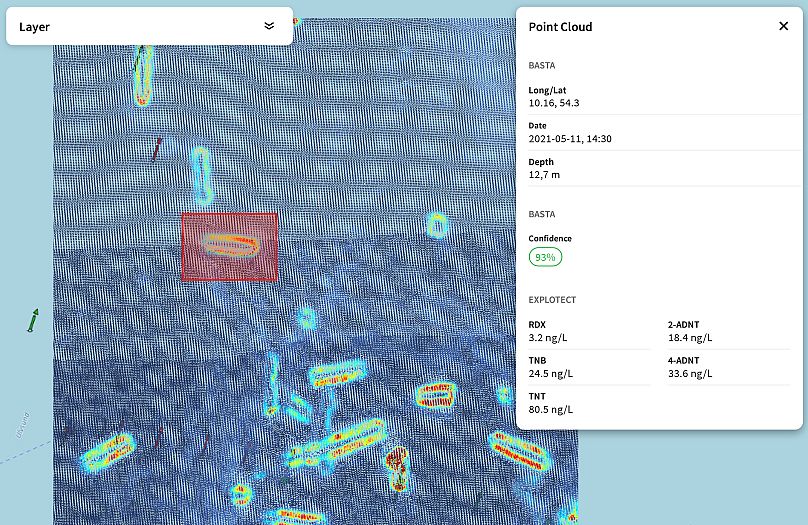

As part of the EU-funded project BASTA, the Kiel-based company is also using AI tools to more accurately scour the seafloor, analysing the weapons and chemical compounds it finds.

For CEO Jann Wendt, technical solutions are waiting in the wings for backing by governments and the EU.

“As soon as there is a financial driver, industry will start scaling, because they will be paid by the amount that they get out.”

How to safely dispose of toxic weapons

Engineers, scientists, policymakers and financiers are currently debating the best strategies for safely destroying the weapons.

Some think the munitions can be tackled where they are, for example by encasing them in concrete. A more permanent solution could be to destroy them through bioremediation. This means encapsulating the munition and injecting it with microbes that will eat the metal and corrosive agents, turning it into a non-toxic by-product.

In Germany, 100 million euros are needed for the prototype of a floating platform where weapons dredged up by robots could be thrown into chambers that detonate them with heat.

But any method of destruction, whether at sea or land, requires careful steps. Detonation is not really a solution if it releases all agents back into the ecosystem, explains Mr Dawson.

Changing ocean temperatures, salinity and density levels are having an unknown effect on the lurking weapons. And as our use of the sea for energy, aquaculture and other resources expands, the race is on to remove them.

The munitions that did make it to the high seas will be the last to be cleared out. But while it seems like a Herculean task, there is at least a finite number to deal with.

“We need to start now the work that will take us another 100 years,” said Mr Dawson. “And I find it really satisfying as a lawyer and an environmentalist to start such an epic project.”