Geography tells the stories of people and planet. But which stories are told - and who is chosen to tell them?

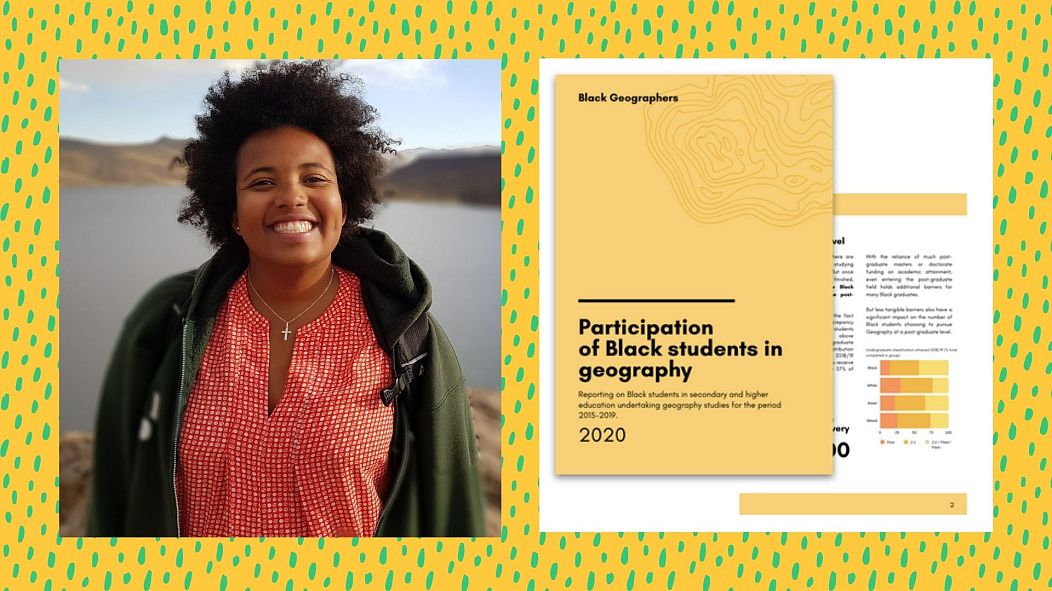

In our first piece celebrating Black History Month, Francisca Rockey, founder of Black Geographers, explains why she launched a movement to diversify her field and the hidden faces of geography.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Geography seeks to study our planet and tell the stories of the people who inhabit it. But what stories are told? And who is chosen to tell them?

A lot of great things start with a tweet.

On 23rd April, I logged into Twitter and felt the overwhelming urge to figure out why - throughout my years of studying geography - I hadn’t been exposed to other Black geographers.

During lockdown, I met another undergraduate geographer online and we discussed what our field could do to improve. Eden and I identified ways to facilitate change within geography, starting with decolonising the curriculum. We also agreed that uptake of the subject during secondary schools needs to be encouraged, something which could be achieved by increasing awareness of career prospects.

Finally we discussed representation, improving the visibility of Black people working within the different areas of geography. This is especially true within physical geography, as it’s not often that Black faces are shown within nature - you are less likely to picture a Black person thigh-deep in rivers, than a white man or woman.

These issues were things that we hoped would change over the course of the decade but that night, something told me to create the change that I want to see and Black Geographers was born.

What is Black Geographers?

The initial idea was to be an Instagram page, where I would document my journey through my degree as a Black Geographer, but I didn’t feel like that was enough. I wanted to do more and I didn’t want to wait for someone else to create the change that we were so desperate for.

I started a Gofundme and registered a community interest company to tackle the erasure of Black people in geography by providing a platform for #BlackGeographers to network and connect.

Since April, we’ve hosted a range of virtual events to build a community. We’ve used our Instagram to focus on specific areas of geography too. Earlier this year we looked at conservation and how to decolonise the movement and make it more inclusive for people of colour, particularly Indigenous people, while considering the role whiteness plays in unfair allocation of resources exclusionary practices.

We’re not the first to address race issues within geography. In February of 2019, three human geographers at the University of Leeds, Monisha Jackson, Olivia Andrews and Bothaina Tashani organised a talk called, ‘Why is My Curriculum White: Decolonising Geographies’.

Their panel highlighted that, “we need demand more from a field that has often overlooked Black spaces, Black experiences, and Black lives.”

A crucial subject in understanding our planet

In one of our recent research papers, we proposed a question: Why aren’t there more Black people in geography?

We found that 7.2 per cent of the total undergraduate students for the academic year 2018-2019 were Black and for geography, only 1.7 per cent of the total admitted undergraduate students were Black.

And this trend is repeated at a staffing level too. In 2018, across the UK, there were only 10 Black geography professors, meaning that only 7 in every 1000 geography professors identify as black.

Beyond this, the image of geography that is perpetuated is that it is a subject for the white, middle class. This is despite geography being a study of earth, its physical features and human activity, which encompasses all classes and races.

So the question is - why is such a crucial subject for our understanding of our planet so unrepresentative of the population?

Our research found that a perceived lack of geography employment opportunities may also be a contributing factor. With Black students more likely to study subjects with clear professional or vocational career paths, the progression of Black pupils into geography undergraduate study will remain limited if the possibilities for future careers are not fully explored and explained at the secondary education level.

How can Black people see a future in geography when they don’t see themselves represented?

Our discipline is heading in the right direction for change but there’s still a lot of work to be done within institutions, like the Royal Geographical Society who should be addressing this issue. Decades have passed, but representation is still low - so why haven’t more organisations taken action yet?

The Black Lives Matter movement may have been a trend to some, but it was the start of a revolution within geography and the geosciences.

We’ve seen the start of The Heritage Fund, a scholarship for Black and mixed Black heritage students developed by us with Esri UK. Additionally, the University of Cambridge has announced a scholarship for 2021-2022 to address historic under-representation in our discipline.

There is a lot of value in improving representation within geography. The discipline will also become more enjoyable, and the research will be more well-rounded when finally led by a truly diverse group of people.