On this day, Gutenberg printed his first bible. It was the first step for an invention that would revolutionise the entire planet. Here's our short history of the printing press.

23 February 1455: Johannes Gutenberg prints the first mechanically printed Bible

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

At any discussion of the most significant inventions in history, conversation will inevitably shift towards one thing: the printing press.

To understand why the printing press is so important to human history, you have to first picture the world beforehand. The early 15th century in Europe was the medieval era. Religious doctrine defined the lives of most people as the study of religious documents was relegated to the few clergy with access to the bible. Information and scientific advancement couldn't spread easily and only around 30% of the population was probably literate.

This all changed with Johannes Gutenberg, a German inventor born in roughly 1400. Close to nothing is known about Gutenberg’s youth, but it’s believed he lived in Strasbourg until around 1444 where he developed the concept of the mechanical printing press.

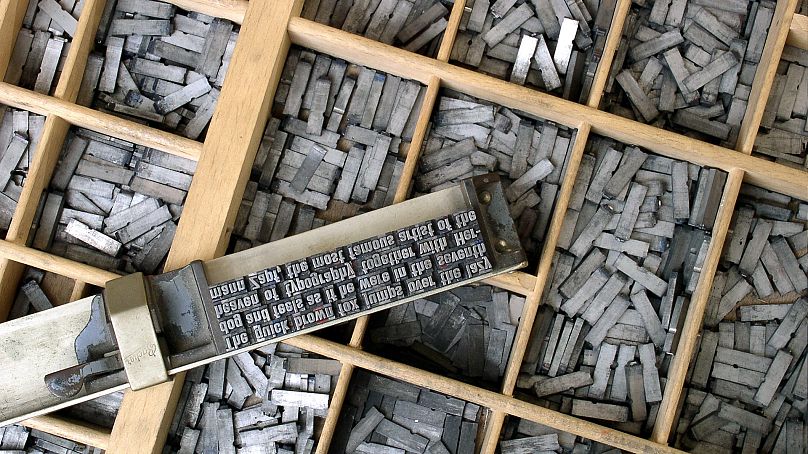

But it was in Mainz, in modern-day Germany, that Gutenberg perfected his invention. The specific details of how the first mechanical printing press worked isn’t certain, but he almost definitely used a form of alloy metal lead type which could be placed inside a matrix mould. The genius of the invention was that the matrix allowed Gutenberg to easily put new types into the press for different pages of text.

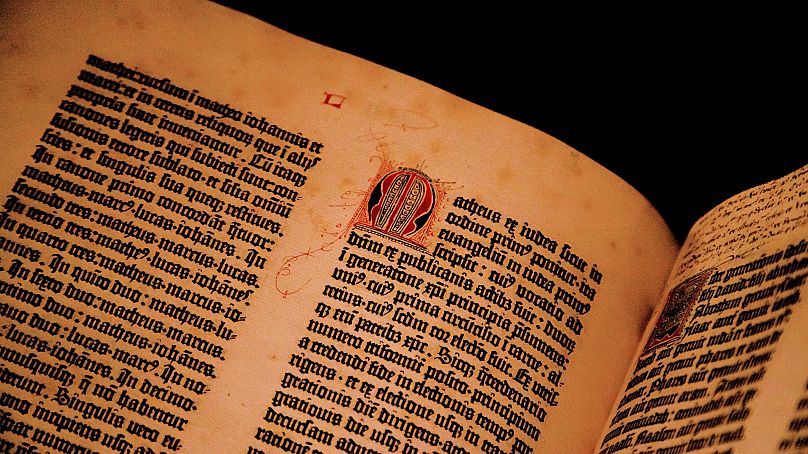

We like the Culture Re-View to be accurate, but today we only have an estimate. Nevertheless, it’s believed that on this day in 1455, Gutenberg printed his first bible. The 42-line Bible, as it was known, was the first commercially available mechanically printed book on the planet.

Until the 42-line Bible, all books created were huge labours of love, often resulting in incredible works of art decorating typefaces in painstakingly bound parchment. Following in that tradition, the 42-line Bible is also a work of beauty. Printed on vellum, the bibles quickly became the talk of Europe with Pope Pius II even raving about the creation.

It’s important to note that in Asia, printing had been invented as early as 220 BC. From the woodblock printing of 6th century China to the moveable-type system invented by Bi Sheng in 1040, the concept of printing in Asia far predates that of Europe. In fact, it’s believed the Asian techniques in printing inspired Gutenberg’s invention. Where Gutenberg is unique is the mechanical nature of his invention, allowing for faster and greater distribution of texts than ever before.

Gutenberg’s press began a revolution of information in Europe. His bibles reached far but it was the mechanical press as an invention that cultural momentum snowballed. By the end of the century, printing had spread to over 270 cities in Europe. Suddenly, the scientific community had the ability to pass knowledge between areas vastly increasing the rate of scientific discovery. Literacy increased, and the concept of individual reading grew.

It’s generally agreed that the proliferation of information that Gutenberg’s invention allowed was a major contributing factor to the Renaissance, Reformation and humanist movements that followed the mediaeval era.

The scientific revolutions of the next 500 years was undoubtedly due to the mechanical press, as was the uprising that brought about the French and American revolutions.

Today, 49 copies of the original Gutenberg 42-line Bible are still in existence, 21 of which are complete. His legacy is long and wide-reaching, with the oldest digital library, Project Gutenberg, taking its name from the inventor.