How scribbled names at an English stately home revealed an elite wartime Polish army unit

When historian Andrew Hann found six names scribbled on the back of a cupboard in Audley End House, he begun a journey to finding out the stories behind six elite Polish soldiers.

Walking around the quiet estate of Audley End House, situated in the countryside between London and Cambridge, you might be mistaken to think the country house simply has a long history of aristocrats wandering to and fro without much to worry about beyond horses and dinner courses.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

You’d be wrong.

What may look like a typical English estate, was briefly the home of an elite training regiment of the Polish army during the Second World War.

May 1, 2022, marks the 80-year anniversary of Britain converting Audley End into a collaborative operation to create a special operative unit of the Polish army called the Cichociemni (pronounced chick-o-chem-knee). Or in English, “the Silent Unseen”.

After the death of Audley End’s owner Henry Nevill, 7th Lord Braybrooke in 1941, the British military took over occupation of the house. With Nazi Germany invading Poland, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), Britain’s espionage organisation, worked alongside the Polish military to train the Cichociemni.

A deadly finishing school

The Cichociemni were trained to be parachuted back into Poland to destabilise the Nazi occupying forces. Audley End was used for the most rigorous parts of the training programme.

They learned unarmed combat, sabotage, how to silently kill someone, safe cracking, and disguises,” Andrew Hann, English Heritage Historian tells Euronews.

Cichociemni would use the surrounding woods for shooting ranges. To train for being in the field, “they’d have to raid the local post office, escaping with some money having not been detected”.

“It was basically a criminals charter for everything you could possibly do to break the rules and cause mayhem in occupied Europe,” Hann says.

They would also be rigorously trained to not give up their false identities. Often they were woken in the middle of the night and asked to recall who they were meant to be.

“They made these interrogations really authentic by dressing in Gestapo uniforms and tying people to chairs and clapping them about a bit. They didn’t pull anyone’s fingernails out, but they made it as authentic as they could.”

Of the 2,613 Polish soldiers who volunteered for special operations, only 527 took part in the gruelling Audley End training programme. Of these, 316 were airdropped into occupied Poland between 1941 and 1945.

103 of the Cichociemni were killed in combat or executed by the Gestapo. Nine more would go on to be killed by the communists after the war was over.

Finding the Cichociemni

For a long time though, very few details were known about the specific lives of the Cichociemni who went through Audley End. There are very few details of the SOE training programme left in the stately manor.

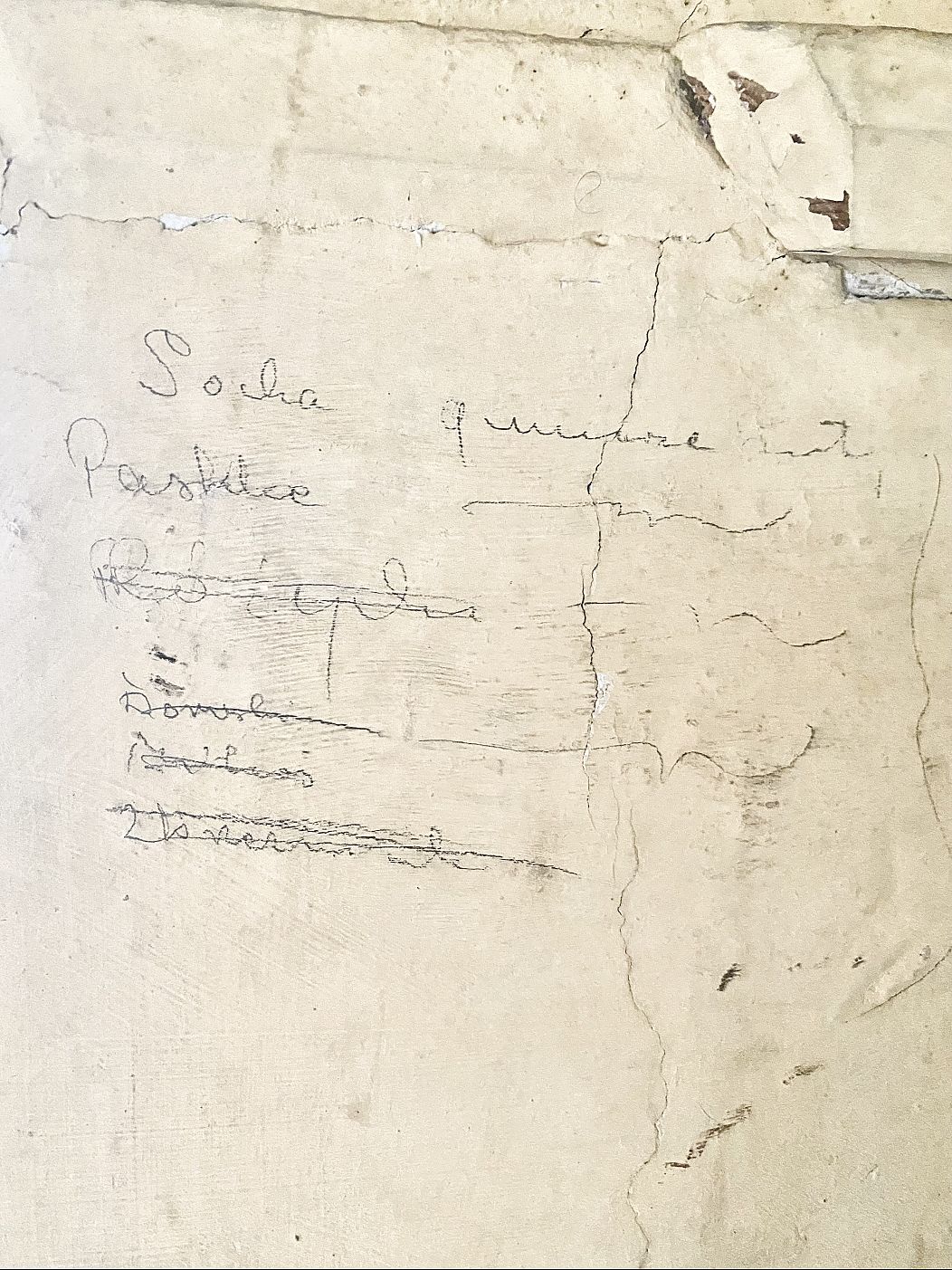

This changed when Hann happened across some names scratched into a cupboard.

“The candle store is on the upper floor. There’s a long passageway where there are these bunkers for storing coal. There’s also a few cupboards for putting candles and other sort of paraphernalia for heating and lighting the house in.”

“It’s basically a service area. There’s a sort of cupboard that you have to walk right into. And then on the reverse just behind the door frame, there’s this list of names down there,” Hann says.

Hann originally couldn’t read the names, but Polish interpreters were quickly brought in to decipher the scribbled handwriting.

Hann worked with historians in both English Heritage and in Poland to uncover details about the list of people on the back of the cupboard.

After coming through evidence, they found a plethora of information about the six individuals who trained to become Cichociemni at the same time.

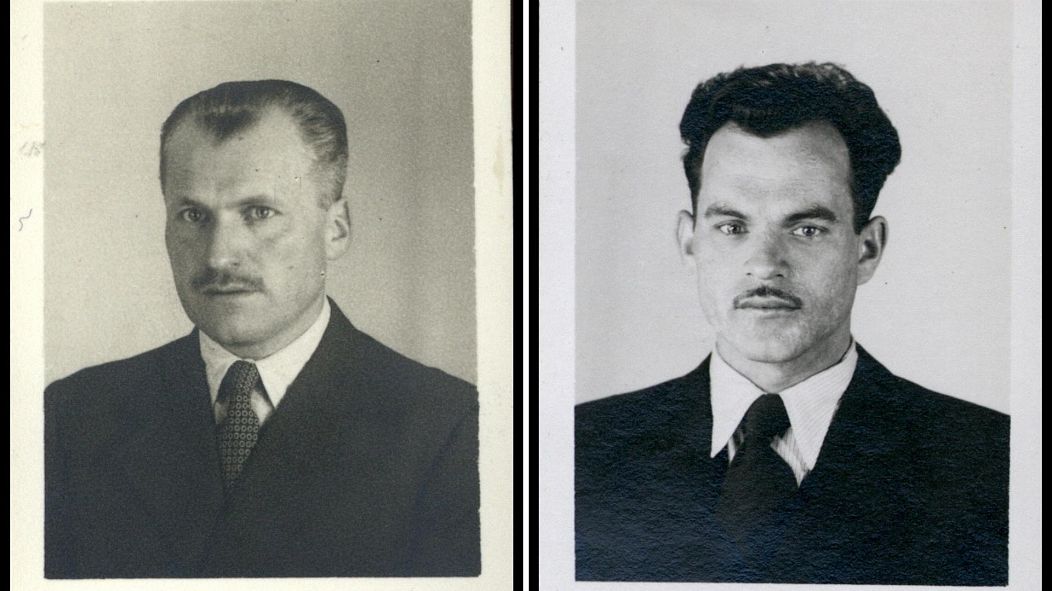

The men were Jan Benedykt Różycki, Teodor Paschke, Franciszek Socha, Jósef Zbrzeźniak, Karol Dorwksi, and Czesław Migoś.

They ranged in age, with Zbrzeźniak at just 22 to Różycki who was 43.

Stories of the Cichociemni

Although all six passed the training course, it was only Różycki who was actually dropped into Poland. At the time they finished their training in 1944, there was a shortage of planes and the Warsaw uprising had reduced the need for them.

Before he joined the Cichociemni, Różycki organised construction gangs to form military battalions to defend the country from the Nazis. When Poland was defeated, he tried to escape via Romania to Yugoslavia.

Unfortunately, for Różycki, he was interned for several months after crossing into Romania. Eventually, he escaped to make his way to France just in time for Germany to invade in 1940. Somehow he makes it to Switzerland where he’s interned again. He escapes and is imprisoned in Spain by the fascists.

Despite the seemingly endless imprisoning, Różycki somehow makes it to Gibraltar in time to be a coffin bearer for General Sikorski, the Prime Minister of Poland’s government-in-exile. Finally, he gets to England to join the Cichociemni.

“So he’s gone through a lot before he gets to England. And then he wants to get parachuted back into Poland,” Hamm says.

Różycki parachutes in and manages to survive the war. Sadly, after the war he is imprisoned again on trumped-up charges by the communists and his son is killed in an attempt to free him.

After his release, Różycki went on to lead a successful life as the director of the Polish Institute of Civil Engineering.

Różycki is a rare example of a Cichocemni who returned to Poland after the war. Many others found it too difficult as they were treated as spies.

Although Socha wasn’t dropped into Poland, he was parachuted into occupied France. From there it is believed he was on a mission for British Intelligence to obtain specimens of poison gas. But he was captured by the Gestapo.

“He was put on a train back to Germany, presumably to be executed. But he distracted the guard and jumped off the moving train to escape. Then he made his way with cuts and bruises to a local farmhouse, and met with members of the resistance who managed to smuggle him to the coast where he was picked up by a submarine,” Hann tells.

Eventually Hann tracked down what happened to Socha by coming across a memoir his wife had written about him. It turns out Socha had met a Scottish woman called Margaret and the two had settled in Dundee with him spending his later years as a teacher.

Socha was from Przemyśl, a town that borders Ukraine today. But his early life was far from a simple Polish childhood. He was born in Vienna in 1914 as his parents had to flee his hometown after the Soviets invaded the Austro-Hungarian empire during the First World War.

“He was born a refugee in Austria. Then his parents return to this small town on the edge of Poland.” His life is beset by warfare between the Soviets and the Poles fighting over the area, while he is trying to train to become a teacher. He studies at Lviv University, which is now in modern-day Ukraine, before the Second World War begins.

To Hann, Socha’s story reminds him of the upheaval of lives during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It also shows the power of historical research in revealing the lives of those past.

“I just followed those six names, but there were 527 people who passed the course at Audley End,” Hann says.

“They are all absolutely fascinating stories of human endurance and heroism.”

An exhibition on the Cichociemni opens on May 2 at Audley End House and Gardens, and will run until 31 October 2022.