In this three-part series, Euronews investigates the reasons why young people in Ireland and Italy are struggling to get on the property ladder or afford rent in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis.

Sophie is just one of 350,000 young adults in Ireland between the ages of 20-35 still living in her family home. Like many millennials in Ireland, the 28-year-old marketing executive from Galway is locked out of the housing market.

This problem is not unique to Ireland. According to Eurostat, approximately 67% of people aged 16-29 in Europe live at home with their parents or relatives. But for some, this is not a matter of choice.

Galway native Sophie told Euronews that rising inflation, coupled with the cost-of-living crisis, is largely to blame: "It's so frustrating, I have a master's degree, a good salary and like so many of my friends I’m saving to buy a house.

"But I had to move back in with Mum and Dad because I was struggling to save money, let alone pay rent. Even now it is going to take me forever to save a deposit," she said.

Affordability is a major issue. Two years ago, for example, interest rates, particularly those set by the European Central Bank, were still at record lows.

"But now we are now seeing situations where quarter upon quarter the ECB is increasing its interests rates by at least half of a base point" Ciarán Lynch, a former member of the Irish Parliament, told Euronews.

The Mortgage Crux

With average house prices in Ireland, 94% higher than those in other EU countries, Sophie's situation is perhaps not surprising.

In order to be eligible for a mortgage in Ireland, first-time buyers are limited to a loan of four times their gross annual income. A prospective mortgage is also capped at 90 per cent of a property's value.

However, house prices across the country have risen 537 per cent since 1988 and are not in line with today's earnings.

According to recruitment solutions giant Morgan McKinley, professionals in Ireland take home an average salary of €45,000. However, the Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO) recently revealed that the average Irish house price is now a record-breaking €359,000.

So, for single-income, first-time buyers with a salary of €45,000, the maximum amount they can borrow is €180,000, which is slightly more than half of the average house price.

Ireland vs Italy

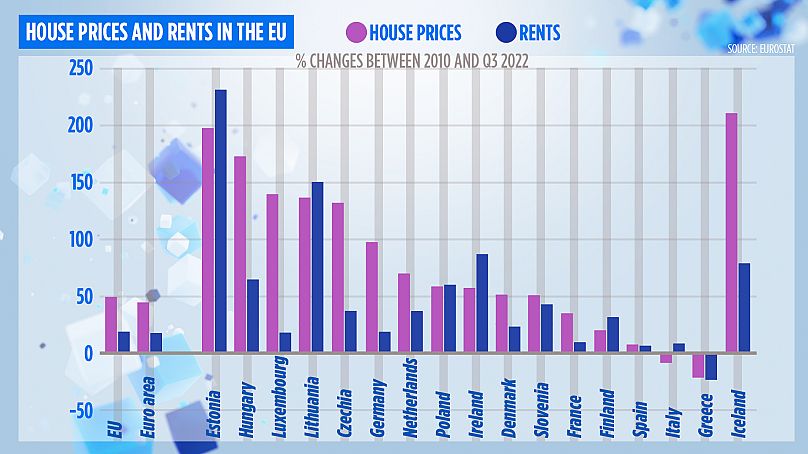

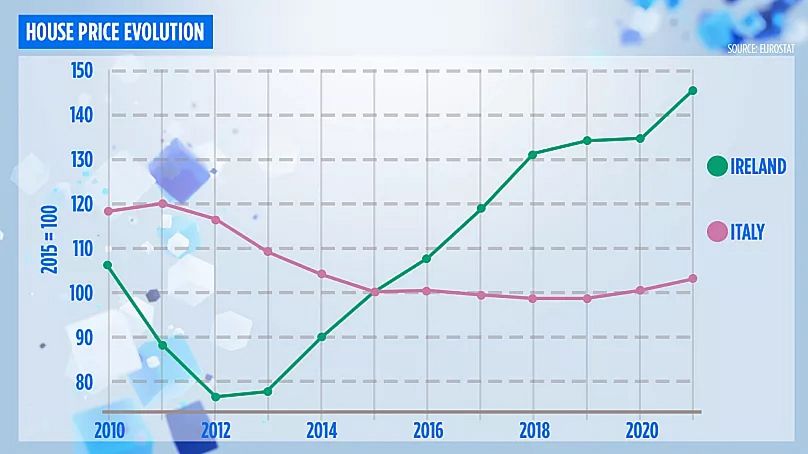

While house prices and rents are generally increasing across the European bloc, in some EU countries property prices have dropped in recent years. Italy, for example, experienced a boom until the financial crash in 2008 and then the cost of property steadily dropped. According to Eurostat, prices were eight per cent cheaper in 2022 compared to 2010.

While rents have increased in Italy, the differences are marginal compared to Estonia, Lithuania, or Ireland where the average monthly rent stood at €1,733 in December 2022, that’s 126% higher than the figures seen in 2011.

If house prices in Italy are more attractive to potential buyers, does this translate to higher levels of property ownership among young Italian adults? On the contrary, a higher percentage of young adults live at home with their parents in Italy than in Ireland.

So, what are the drivers behind this trend in both countries?

Ireland's lack of supply

While median gross salaries in Ireland are considerably higher than in Italy, available homes are also few and far between on the Emerald Isle.

"In 2010, we had 24,000 rental properties advertised on Daft (Ireland’s top property site) on any one day of that year, compare this to recent figures when we had just 700 properties available right across the country,” said Mark Rose, the managing director of Rose Properties, Cork.

“So now we have approximately 3 per cent of what was available in 2010. We need thousands of rental properties to be loaded onto the market today, tomorrow or as soon as possible. They are urgently, urgently needed,” Rose added.

The limited availability of properties is increasing demand and placing a serious strain on rents and potential buyers.

Roy Dennehy, managing director of Dennehy Auctioneers, told Euronews: “The rental market in Ireland is totally and utterly dysfunctional. We put a house up to rent two weeks ago at 12:55 pm and by 13:20 pm we had 90 emails (enquiries)."

“We need thousands of apartments in cities to keep up with demand. However, Ireland is a victim of its own success. A lot of people want to come and live and work in this country and are attracted by the lifestyle, but our population is also growing and we can't keep up,” Dennehy said.

The Central Statistics Office estimated that the population in Ireland increased by 88,800 persons from April 2021 – April 2022, the largest 12-month population increase since 2008. This is largely due to a 445 per cent surge in migration, and according to Dennehy, foreign direct investment is part of this trend. “Ninety per cent of the inquiries I am currently receiving for a new housing development in the town of Carrigaline, Cork, is from non-nationals, and ninety per cent of those again are non-EU”.

“The professionals coming here have good jobs, they are well paid and they love this country”.

But former deputy Ciarán Lynch, who chaired the Committee on Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform in October 2012, said non-nationals with money to burn are also running into problems.

"Foreign direct investment is a very, very significant part of the Irish economic model," he said.

"And job creation has become a problem because it's not that the jobs aren't there, but the houses aren't actually there for the employees when they get those jobs."

The Italian job

"Property might be cheaper in Italy but the problem lies with the country's stagnant labour market," said Mimmo Parisi, a sociology professor from the University of Mississippi, who is a senior adviser for European data science development.

Parisi told Euronews: “Everyone is looking for that dream job in Italy and professionals don't move around much, once they find a dream position they stay, often for life. As a consequence, there are fewer job openings and it's difficult for young adults to enter the job market".

High unemployment among youths in Italy is a major factor. According to Italy's national statistics institute, ISTAT, the unemployment rate for youths (aged 15-24) was 22.9 per cent in January 2023, nearly eight points higher than the EU average of 15.1 per cent. As a consequence, young Italians are less financially independent.

"Add dubious work contracts, slow wage growth and low salaries to the mix and it is easy to see why young Italians are stuck at home despite falling house prices. It is also difficult for university graduates to secure relevant short-term work experience when the labour market works in the favour of an ageing workforce," explained Parisi.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Italy is the only European country where wages fell between 1990 and 2020, all the other Member States experienced a rise with Lithuania leading the charge with a 276.3 per cent increase.

"Many students stay in university that bit longer when hunting for that dream job, which as we've learned is difficult to come by. This forces young adults to be more reliant on their parents until that happens," Parisi said.

Banks place another obstacle in the way of young Italians. An Italian bank will not approve a mortgage without a permanent work contract otherwise known as ‘il contract contratto a tempo indeterminato’, which creates additional obstacles.

Click on the link below for the next article in this series