As he begins what could be a five-year trial at the Hague on war crimes charges, Thaci's political career in Kosovo looks like it is finally over.

The indictment of former Kosovo President Hashim Thaçi for war crimes committed in the 1998-1999 conflict, while rumoured for years, stunned both Kosovo and the wider European public when it was finally announced last September.

For decades, he was front and centre at negotiations with Western leaders over the establishment of Kosovo's independence.

Now, his reputation – and the country's – could be tarnished by allegations that he either participated in or bolstered the torture, kidnapping and murder of civilians when he was the political leader of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerilla force active during the Kosovo War.

Professor of political and cultural sociology Eric Gordy says that Thaçi's departure from politics represents a sea change for the country.

"I think the main thing is that it marks a generational change — the exit from power of the war veterans, after only 13 years [since its declaration of independence]," says Gordy.

The Balkan region is still largely ruled by politicians who rose to power or maintain the legacy of Yugoslavia's bloody dissolution after the fall of communism three decades ago.

"This is important for the whole region, where, in most of the post-conflict states the monopoly is still in the hands of people whose legitimacy is tied to the national projects of the 1990s," says Gordy.

Gordy believes that the citizens of Kosovo felt a collective sense of relief when Thaçi resigned, even if it was to face war crimes charges.

"The impression I get in conversations with people from Kosovo is that a lot of people are just happy to see just anything that gets rid of his monopoly if that's what it takes," he stated.

It also shows others that no one – no matter how popular in the West – can avoid being investigated for war crimes, added Gordy.

"I've heard people using this as a warning, saying you may think that the West will protect you, but they don't protect anyone," Gordy said.

Thaçi resigned in November of last year to face charges for war crimes and crimes against humanity at a special court based in The Hague.

While the Specialist Chambers held five status conferences in Thaçi's case by May, the actual trial is not expected to start before 2022, according to his attorneys.

The indictment, announced in June 2020, features 10 counts including kidnapping, torture, and the murder of civilians. Thaçi and five other former KLA members are being charged with joint criminal enterprise, a legal concept used to prosecute members of a group for the actions of the entire group within a common plan or purpose.

Thaçi will likely be the last top political figure from the region to face war crimes charges after coming to power in the 1990s. It is widely understood that he will not make a return to politics regardless of the trial's outcome.

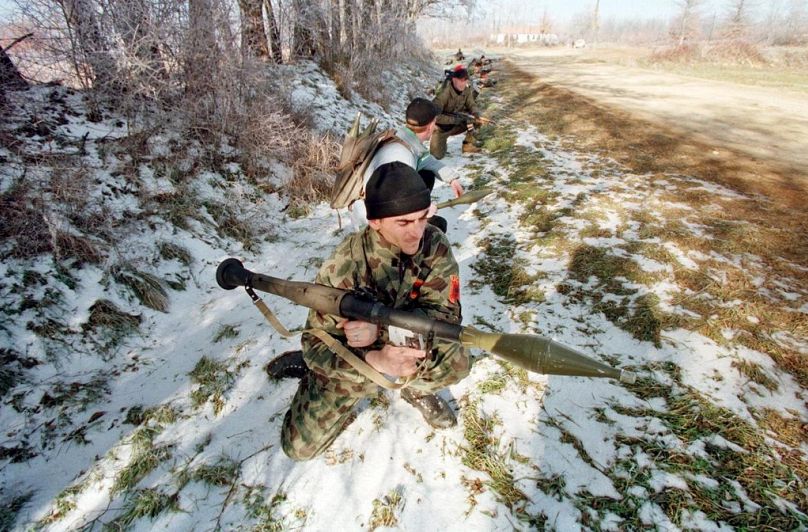

Thaçi was a young history graduate in the 1990s when he joined ethnic Albanian dissident groups in forming guerilla cells to fight back the police and military crackdown in Kosovo.

As the Yugoslav socialist federation fell apart, and wars broke out in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia's southern province sought to break away and shape its own path towards independence.

Yet Thaçi was a nobody at the time. Few would have predicted his rise to power when he was plucked from relative obscurity in 1999 and selected to lead the Kosovo delegation of the talks held in Rambouillet between Serbian representatives and those representing the ethnic Albanian majority in Kosovo.

"It was not clear even to those covering the Kosovo conflict up close how Thaçi was selected as the leading figure of the negotiations in 1999," said Ismet Hajdari, a veteran journalist who covered Thaçi since his time reporting on the armed conflict in Kosovo in the 1990s.

"The Kosovo Liberation Army was scattered at the time. The Americans wanted someone who had some legitimacy among the masses, who could help implement any agreement that was achieved. This would also be an easy way to place the KLA under their control," explains Hajdari.

Thaci versus Ibrahim Rugova

The choice of Thaçi over Ibrahim Rugova, a writer and Kosovo's most prominent political leader at the time who advocated for the country's independence through peaceful means, baffled even the negotiators at the talks.

"Rugova had the democratic mandate to lead negotiations for Kosovo Albanians since the majority elected him president. Yet Rugova couldn't guarantee that what was agreed on would be implemented, while the KLA could."

Hajdari believes that the main goal of the West at the time was to find a way to control the entire KLA from within, instead of attempting to build bridges between the guerilla fighters on the ground and Rugova.

The disagreements between Rugova's Democratic League of Kosovo – the first political party formed in Kosovo after the fall of socialism – and Thaçi's KLA ran deep.

Rugova had participated in several failed talks with Slobodan Milošević, the president of Serbia, who was responsible for withdrawing significant political rights for Albanians within Yugoslavia before it fell apart.

The Yugoslav constitution of 1974 had given the province almost the same status as the six republics within the Yugoslav federation. Yet when Milošević came to power, independent voices were jailed or persecuted. Protests erupted that were violently quashed by the federal military forces.

Resentment grew as Kosovo's Albanians increasingly rejected the idea of Belgrade's firm rule amid growing backsliding on Albanian language and political rights, including the curbing of Albanian-language media, education, and free elections.

Rugova believed it was foolhardy to set up armed resistance against Serbia, considering that it had inherited much of Yugoslavia's significant military capacities.

He also knew that Serbia would use any form of armed resistance by the Albanians to depict them as rabble-rousers who could not be trusted with power.

Rambouillet talks

Western powers grew frustrated with the promises Milošević made – and subsequently violated – in agreements reached with Rugova. In Thaçi, they saw someone who could be used as a vehicle to speed up the process of wrapping up the Kosovo issue.

"The first time we really saw Thaçi was at the Rambouillet talks," says Hajdari. "It's not like we were impressed, but the US presented him as a great leader and an unavoidable factor in achieving a settlement for Kosovo."

The West needed the Rambouillet talks to work because they wanted to present Milošević with an ultimatum as a means to getting him to stick to the agreements they facilitated.

Should the talks fail or an agreement be disrespected, NATO would respond with airstrikes – which was a deeply unpopular move among certain alliance members.

But Rambouillet turned out to be the peace talks that weren't. With the Milošević government refusing to allow NATO peacekeepers on its soil to implement the agreement, NATO moved swiftly to outright military action as ethnic Albanians left Kosovo in hundreds of thousands, expecting a further escalation of atrocities directed from Belgrade.

From Marx to menswear

Thaçi used the NATO intervention and the subsequent withdrawal of Belgrade-controlled forces to solidify his newfound status as the darling of the West, exchanging his camouflage uniform for tailor-made suits.

He also went from a Marxist-Leninist dissident to a western-style politician overnight, discarding his ideological motivations and embracing the mantra that would follow him for the rest of his career – to maintain power at any cost.

"His political rhetoric was never clearly or concisely articulated," says Hajdari. "Even later, after he fully matured as a politician. His main ideology was power and the continued generation of said power."

This spelt trouble for the most well-known UN protectorate, which Kosovo was from 1999 until it declared independence in 2008. While Thaçi would meet with western leaders and promise to adhere to agreements, his tendency to place himself at the centre of political events disrupted even the best-laid plans.

"The first head of the UN Mission in Kosovo, Bernard Kouchner, famously said that "everything Thaçi built during the day, Thaçi destroyed at night". But the international community needed Thaçi because he could give them what they wanted: security, safety, and order and peace in Kosovo," explains Hajdari.

Former minister-counsellor at the US Department of State Daniel Serwer, who played a significant role in peacebuilding work in the region, thinks that Thaçi was the only one who could successfully manage the transition, because his role in the KLA during the 1998-1999 conflict was strictly political.

"In my view, he did what we wanted him to do. He went from bullets to ballots. And I think it was relatively easy for him because I don't think he was really a fighter," says Serwer.

"With Hashim Thaçi, I don't think there's any real history of active fighting. I think he was a political spokesman like the IRA's Gerry Adams and the de facto civilian leader of the organization," Serwer further explained.

Since then, Thaçi was busy solidifying his image in the West, with frequent trips to Washington DC to help him learn English and constant dinners with those influential in the diplomatic circles.

Op-eds in the New York Times were followed by a full-length biography, "New State, Modern Statesman," in which he gets compared to internationally renowned freedom fighters such as Nelson Mandela.

The impression is that his biography was written with one purpose: to give Thaçi legitimacy post factum - that is, to fill in the blanks prior to the Rambouillet talks. Some of the narrative might be true, while some reads as pure fiction.

Thaçi never shied away from hiring PR companies to do his bidding, either. When he embraced the idea of a territory exchange between Kosovo and Serbia at the height of the EU-moderated Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, intended by the international community as a path to the solution of what they saw as the biggest dispute in modern-day Europe, Thaçi hired a Paris-based company, Majorelle PR & Events, to find anyone from journalists to academics who would be willing to endorse the deal.

Serwer, self-described as one of many Americans Thaçi saw as useful, claims that he was also quick to ghost anyone who would oppose his latest political play. "One time in fairly recent years we sat down. I was actually concerned about the land swap proposal. I became a very strong opponent of the land swap idea, and he dropped me like a hot potato," states Serwer.

The proposed land swap, which would have seen the Preševo Valley in southern Serbia -- with its majority ethnic Albanian population -- join Kosovo, while Serbia would regain control over the land north of the River Ibar, never took place.

In addition to the critics of the proposed deal pointing out that redrawing borders further solidifies the mono-ethnic communities the West has tried to prevent in the Balkans, it also exacerbated fears that any territorial exchange might justify similar deals in other countries in the region, such as Bosnia.

Back on track

For Thaçi, who was already aware that the Kosovo Specialized Chambers were looking into his possible involvement in war crimes, the land swap seemed like a way out of his own troubles. "He was even prepared to enter a deal on the division of his own country with Serbia, solely to legitimize himself in the West as so unavoidable, that he should not be bothered with any indictments from the Hague," explains Hajdari.

But Thaçi's last ploy failed, so he now awaits what is poised to be a very lengthy trial. His departure from the political scene could be the opportunity the country needed to get back on track to becoming the region's most vibrant democracy.

"I think that the alignment of the stars at the moment when Kosovo declared its independence wasn't so lucky for the country in terms of the person who'd lead it," Hajdari says.

"Thaçi left the country at the top of the list of Europe's most under-developed countries, leading in poverty, joblessness, unemployment, corruption, organized crime, and gender discrimination.

"During his reign, we failed to create a great story about Kosovo that we could proudly present to the world as a major justification of its independence," he concludes.

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.