A century on from the partition of Ireland, communities in Northern Ireland are as divided as ever. Is reunification the answer?

The first one hundred years of Northern Ireland's existence is ending as it began - with violence on the streets of Belfast and unionism in crisis.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The Belfast riots from 1920 to 1922 - known by some as the first Troubles - were a knee-jerk reaction by loyalists troubled by the raging guerrilla war against the UK and the perceived threat of being wrenched away from its bosom by southern nationalists.

For some, history appears to be repeating itself in 2021.

Just weeks after some of the worst rioting in the capital for years, the first minister and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Arlene Foster announced her resignation on Wednesday after a revolt against her continued leadership by the party's rank and file.

"The future of unionism and Northern Ireland will not be found in division," Foster said in her resignation address. "It will only be found in sharing this place we are all privileged to call home".

Despite her conciliatory tone, unionism continues to tear itself asunder as it grapples with the direct challenges to its core principles wrought by Brexit and an infamous clause in the UK-EU trade deal at the heart of the current polemic, the Northern Ireland Protocol.

But while the UK's departure from the European Union has been widely cited as the root cause of the latest upheaval in Northern Ireland, it's just another convulsion brought on by a deep-seated social malaise that unionist leaders have been unable to prescribe a remedy for.

In the country's centenary year, with unionism losing its footing on increasingly unstable ground, is it time for all those with a stake in its future to begin planning for the reunification of Ireland?

The path towards a united Ireland

On the face of it, is a difficult question to answer, not least because the past century has known so few years without bloodshed, sectarian violence or political rancour.

"Northern Ireland had a cruel birth," wrote Northern Irish poet and novelist Seamus Deane on the partition of the island in 1921 following the Irish War of Independence.

The cleaving of six countries in the predominantly Protestant, unionist province of Ulster from the Catholic, nationalist southern provinces ultimately sowed the seeds of the ethno-nationalist violence which was later to be reaped during the Troubles.

Now finding themselves in a majoritarian Protestant country, Catholics were soon the subject of microaggressions as well as discrimination for jobs and housing. Communities became segregated along sectarian lines, which in places like Belfast still remains in place with order between the two maintained by dividing Peace Walls.

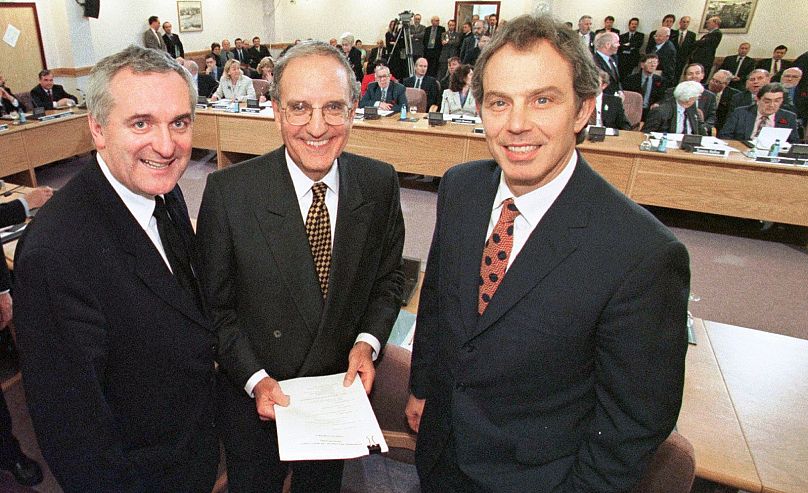

While the historic Good Friday Agreement - brokered by political leaders of all stripes in Northern Ireland, the US, UK and Ireland in 1998 - removed the gun from Northern Irish politics, it has not yet wholly resolved more than a century's discord and division.

There is however evidence that seismic demographic shifts are taking place in Northern Irish society which are putting the country's place in the Union on the table for debate.

In an opinion poll published in January by the Sunday Times, more than half of respondents said they wanted a referendum on unity within five years.

While the majority of those still favoured to stay part of the UK on 47 per cent compared to those who backed a united Ireland on 42 per cent, a crucial 11 per cent were undecided on the issue.

It's this grey area that is sparking debate on the country's future.

"There can be no question that people are openly discussing the constitutional question like never before," Emma DeSouza, a political commentator and prominent civil rights campaigner in Northern Ireland, told Euronews.

"And I think that stems from the fact that Brexit and all of its outworkings are being rolled out against the wishes of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland".

DUP's handling of Brexit

The DUP under Foster's leadership was the only party in Northern Ireland to actively campaign for Brexit in the EU referendum campaign. In its aftermath, the party entered into a supply and confidence agreement with then-prime minister Theresa May following the 2017 general election.

However, Boris Johnson's final deal with Brussels (which was not supported by the DUP or any other Northern Irish political party) has been a particularly bitter pill for many loyalists to swallow, not least because of the imposition of new customs checks on trade between the UK and Northern Ireland.

The presence of a de facto border in the Irish Sea between the rest of the UK and Northern Ireland has inflamed the anger of unionists who feel betrayed by the government in London and the DUP. So much so, earlier this year there had been threats of violence made against port workers as well as legal challenges launched against the protocol by the DUP.

"Instead of negotiating a soft Brexit that takes into account our delicate peace process and the democratic wishes of the people of Northern Ireland, the DUP used its position to say no to every option on the table, leaving us with the NI protocol," contends DeSouza.

For her, having successfully fought a five-year-long battle with the UK Home Office to secure her rights to identify as Irish as ascribed to her under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, any future decision will be made on the basis of equality and continued peace.

"In terms of the constitutional future, I believe much in the same vein as Germany, reunification is now an unstoppable force," she said.

"The gains of the peace process mean that identity lines have been softened. Unionism no longer holds a majority in Northern Ireland.

"The majority want the future envisaged in the Good Friday Agreement, rights-based with equal opportunities. To many, that future now seems far more likely as part of a united Ireland."

Segregation persists

Recent images of a hijacked bus ablaze, police and armed cars pushing back crowds of hooded rioters and Molotov cocktails being thrown at the Peace Wall in Belfast, however, help paint a less hopeful picture of life in Northern Ireland.

For Sorcha Eastwood, an Alliance Party councillor on the Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council who represents a ward in loyalist heartland, the rising tide of unionist disaffection towards their elected leaders is clear - and it's not just Brexit that is the cause.

"I represent those people as much as they [unionists] do. And what we've seen is that there are unionists who are more coming towards us now because they don't particularly see themselves reflected in elected unionism," she told Euronews.

Alliance - a cross-community, centrist political party founded in 1970 with the aim of healing sectarian divisions - has had growing success in elections across Northern Ireland in the last decade in large part to its neutral constitutional stance, gaining its first MP at Westminster in 2010.

For Eastwood, the scenes in Belfast are more than just anger about the changing status of Northern Ireland within the UK following the EU referendum.

Of course, Brexit has had an impact, she argues. The police's decision not to pursue senior republican leaders in Sinn Fein over COVID-19 rule breaches when they attended the funeral of prominent IRA member Bobby Storey also lit the touchpaper.

But social deprivation and the absence of any credible unionist leadership in solving persistent social issues are at the heart of Northern Ireland's current turbulence. Nowhere is this felt more than in the areas of south and west Belfast where the riots broke out.

"You can travel within less than three-quarters of a mile and you've got one of the most deprived areas in Northern Ireland and one of the richest, within three-quarters of a mile of each other within the same constituency," said Eastwood.

"And that is an issue because you clearly cannot encourage people to aim for something better if they feel at the moment, 'I don't have anything'. And there's a level and an element of hopelessness and despair creeping into some of these communities that they've never actually quite been able to shift and shake off and get rid of".

It is not just in the working-class communities in Belfast that this apathy has taken root. The feeling that loyalist communities have been forsaken is endemic across the country.

"Where I am in Lagan Valley, it's one of the most affluent constituencies in the whole of Northern Ireland. It's I think it is the most affluent local government district for Lisburn-Castlereagh but there are still pockets of deprivation albeit small," said Eastwood.

"But they are loyalist estates predominantly and they have really managed over the years, to do a good job of getting people involved, to try and to promote better life chances, trying to address educational, and health inequalities.

"I'm not saying that they're perfect, but we haven't necessarily seen that work and that reconciliation pace. And that's now where you see disaffected people who, frankly, for a lot of them, haven't been able to see the peace dividend and a lot of that is because we have this continued segregation, in housing, and schools.

"And even recreation activities, where people go or choose not to go. Or there's an unwritten rule: 'Oh I wouldn't go there. I wouldn't necessarily feel comfortable there'".

Co-operation rather than unity

While a united Ireland may be an attractive prospect for some communities in the North, achieving it will likely not be a prospect even in the long term.

For one, the grounds for holding a referendum - the principle of consent across communities in Northern Ireland and on both sides of the border - are not yet met.

These iron-clad terms were laid out in the Good Friday Agreement and overwhelmingly endorsed in referendums in 1998 by the people living in both the North and South.

With recent polling data indicating neither a strong preference for the Union or a united Ireland, Northern Ireland finds itself in a constitutional limbo.

While the appetite for unification may not yet be hungry enough to push for constitutional change, there is a growing urgency at least in increasing cross-border cooperation, given the two countries' shared geography and history.

While leading politicians in Ireland's traditional establishment parties Fianna Fail and Fine Gael are exercising caution in regard to any future border referendum emphasising the need to build consensus first, work is ongoing to build closer ties with the North.

This has taken many forms, including cross-border health services and policies which would facilitate a more balanced all-Ireland economy.

Though she herself believes a united Ireland is ultimately inevitable, DeSouza is seeing the fruits of cross-border co-operation firsthand when she took part in the first Shared Island Dialogue, an event organised by the Irish government's Shared Island Unit, which brought together 80 young people from the North and South.

"I was truly taken by the determination of all those participating to create a rights-based society of equals. There was no border in that discussion; both young people from the North and young people from the South shared the same aspirations," she said.

Through her work to defend civil liberties and foster further cross-border co-operation on key issues particularly to do with preserving the Good Friday Agreement, one thing is pointedly clear for her.

"The DUP don’t represent the majority of the people in Northern Ireland," said DeSouza. "They are a party that hasn’t quite realised that this isn’t 1921 – it's 2021".

Every weekday at 1900 CEST, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get an alert for this and other breaking news. It's available on Apple and Android devices.