Agreed on November 21, 1995, by the heads of the warring factions in the Bosnian war, the Dayton Agreement brought hostilities in the Balkan country to a close. What does it mean now for Bosnia 25 years on?

Bosnians had a vested interest in the result of this year's US presidential election. In the days following November 3 - polling day in the United States - messages of congratulations for President-elect Joe Biden poured in from the Balkans.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In Sarajevo, the Bosnian flag and the Stars and Stripes were projected onto the facade of the city's National Library with the words "Bosnia remembers" and "Unity over division". It's perhaps fitting that Biden's elevation to the presidency falls in the same month that Bosnia and Herzegovina reflects on 25 years of peace.

For many, his election brings into sharp focus Bosnia and Herzegovina's continued efforts to move forward from the devastating war which ripped it apart in the early 1990s. Biden, for his part, was one of the strongest supporters of lifting an arms embargo imposed on the warring factions and called for US intervention to end the genocide of Bosnia's Muslim population when he was a US senator.

The US and NATO intervention that eventually came ultimately led to the Dayton Agreement, brokered at an airbase on American soil in November 1995 under the auspices of President Bill Clinton. While the accords agreed a quarter of a century ago today (Saturday) brought the war and killing to an end, it continues to have a chequered legacy.

What was the Dayton Agreement?

Agreed on November 21, 1995, at an airbase in Dayton, Ohio in the US, the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, or the Dayton Agreement or Dayton Accords as it became known, officially brought the Bosnian War to a close.

By the time it was officially signed by the presidents of Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia in Paris weeks later on December 14, over 100,000 people had died in a bitter conflict which saw the first ethnic cleansing in Europe since the Second World War and over two million people displaced.

While the overarching aim of the accords was to bring peace to the region, the agreement - which was also signed by US President Bill Clinton, British prime minister John Major, German chancellor Helmut Köhl, French president Jacques Chirac and Russian prime minister Viktor Chernomyrdin - also laid the foundations for the federal state of Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to end the de facto division of the country.

In essence, the disputed Bosnian territory was divided roughly in half between two entities, the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska. While each entity is highly decentralised, it was agreed that Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole would be governed by a constitution and a national government with a rotating presidency, as set out in the terms of the agreement.

What has its legacy been?

The peace deal, of course, didn't put an end to regional tensions, with resentments running deep following a catastrophic, divisive conflict drawn on ethnic lines. Over the course of three and a half years, Bosnian Serbs fought Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) and their erstwhile allies Bosnian Croats over territory in the region as Yugoslavia imploded.

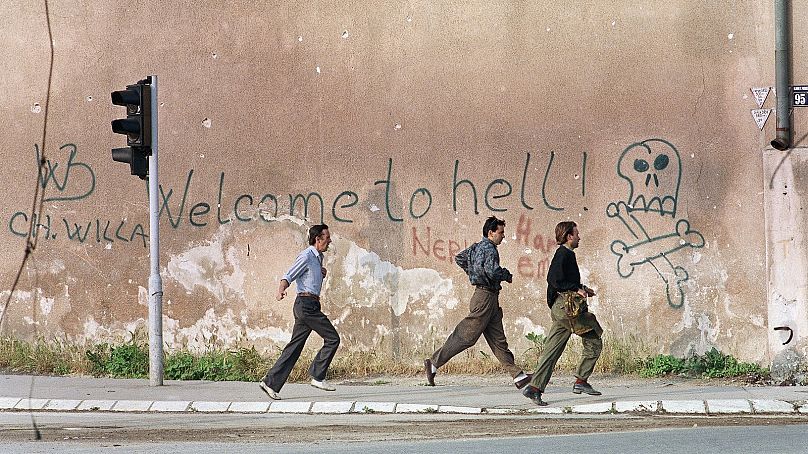

During the course of the war, many atrocities took place, including indiscriminate killings and shelling of towns and cities, as well as acts of genocide. For 22 months, Sarajevo was besieged by Serb forces, with snipers picking off citizens one by one from the surrounding hills in the longest siege of a capital city in modern times. The now infamous massacre of Bosniaks in the enclave of Srebrenica, which took place just four months before the peace accords were agreed, saw 8,000 men and boys murdered and buried in killing fields around the town by Serb soldiers.

While on an international stage, the "intensity of purpose" which forced the belligerents of the war to the negotiating table has seemingly translated into over two decades of calm, the co-existence of former enemies in such close proximity has done little to assuage anxieties on either side. The state of Bosnia and Herzegovina remains a rigidly divided country still coming to terms with the events of the 1990s.

"The Dayton Peace Agreement created a power-sharing system that stopped the bloodshed but did not provide democracy. That is both its greatest success and biggest failure," Amila Karačić, Deputy Program Director at the International Republican Institute in Bosnia and Herzegovina, told Euronews.

The reaction of many Bosnians to the election of Joe Biden, for instance, speaks to this need to recalibrate, with the hope that as president, he may once again make the US a key player in the Balkans. It is, after all, becoming a flashpoint between the US' European allies and an emboldened Russia. Recent elections in neighbours Serbia and Montenegro in June and October respectively have been pitched proxy battles between pro-European and pro-Russian parties. Bosnia's continued instability is a risk of destablising the region further as well as having the net result of being driven further away from NATO and the EU.

As a mechanism to end armed hostilities, the Dayton Accords were arguably effective having secured 25 years of peace and counting. As a long-term solution to the causes of the war and the lasting damage it caused, it has not faired as well. It was not designed to permanently ease bristling tensions between the various ethnic cleavages in the country and in turn, how these interactions affect the governance of the country.

"A quarter of a century later, the political environment in Bosnia and Herzegovina is still dominated by nationalist rhetoric that provides the perfect cover for corruption scandals, lack of accountability and opportunism," Karačić added.

Couple this to the stagnation of wages and the endurance of low incomes which have precipated a "brain drain" of the country's young people who are actively seeking a hopeful future abroad, the outlook for Bosnia and Herzegovina's future remains shrouded. However, It is not all doom and gloom for the country, according to native Karačić.

"Nevertheless, there are pockets of optimism and hope, and local success stories in parts of the country that can be the seed of the future Bosnia and Herzegovina. These stories are important, not only because they show the pluralistic, multi-ethnic, and progressive nature of the country, but also because they prevent us from becoming entirely cynical about democracy in Bosnia and Herzegovina".