Several drugs are being used to treat COVID-19 but which ones are actually effective in helping to lessen the effects of the virus? Euronews talks to an expert in intensive care medicine to debunk the myths.

With dozens of clinical trials in progress, the world waits with bated breath to see if a viable COVID-19 vaccine will be available in the near future.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Scientists at the University of Oxford gave reason to hope earlier this month after the peer-reviewed findings of the establishment's initial clinical trial showed that its experimental vaccine had produced anti-coronavirus antibodies.

It is an exciting development in the hunt for a future vaccine but is far from offering a definitive solution to the pandemic.

As the number of COVID-19 cases still mounts around the globe, including spikes in countries that have eased lockdown restrictions, the daily focus of healthcare professionals continues to be alleviating symptoms of the disease.

But it's not easy. Given the nature of the virus, there is no silver bullet to treat it. While some medicines and therapies have been touted as wonder treatments, most are being used cautiously and, in some cases, without clear medical evidence of having any benefits whatsoever.

"With a lot of the drugs, there's still uncertainty. With some of them, there's certainty," Dr Tim Cook, an honorary professor of anaesthesia at the University of Bristol and an anesthesia and intensive care consultant with 22 years experience, told Euronews.

Remdesivir

As with many drugs being used to treat COVID-19 symptoms, remdesivir is still the subject of laboratory studies gauging its effectiveness. An anti-viral drug, it is designed to hamper an enzyme the virus uses to copy its genetic material. And while it has been roundly approved for use in the EU by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), as well as already being in used in Japan and the US, it remains problematic.

Of two early studies, only one, a randomised trial of 1,000 patients conducted by Dr John Beigel and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed modest benefits to patients who had been prescribed the drug. However, the study has been called into question, Cook says, not least because the methodology was changed mid-trial which has cast doubts on the data collected.

It did show that remdesivir had the best therapeutic effects on lower-risk groups, such as young, white patients who were on oxygen but didn't need to be ventilated. "It seemed to have less benefit the sicker you were," he explains.

"If remdesivir has any effect, it is to shorten the illness. There's no clear evidence that it improves survival and there's no clear evidence that it shortens the disease in the sickest patients," he adds. "It's controversial, therefore, that it's been fairly widely approved."

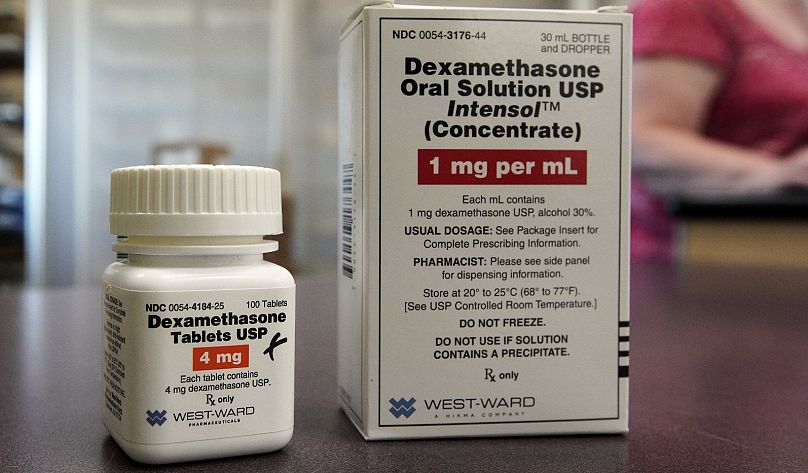

Dexamethasone

"I think all patients with severe disease should be on dexamethasone unless they have a contrary indication," Cook contends. Dexamethasone, according to studies, is demonstrably the most effective available drug in reducing mortality rates in critically ill COVID-19 patients. The Recovery study, which Cook calls "remarkable," recruited 12,000 patients over three months. As many as 15 per cent of all COVID-19 patients in UK hospitals were admitted to the trial, which showed that 1 in 8 patients on ventilators who were given dexamethasone improved.

Given the depth of its scope, Cook believes it is the most definitive drug study to date and leaves few if any questions unanswered as to its effectiveness. "The results were so impressive that the day the results were released... the Department of Health authorised its use across the UK," said Cook. "Although, frankly, given the results, I think clinicians would have made that decision for themselves."

Its therapeutic value is not the only benefit of dexamethasone. As it is off-patent, the once-a-day injection or tablet is extremely inexpensive to produce and available around the world. "It's not a panacea but its an important therapy," Cook concludes.

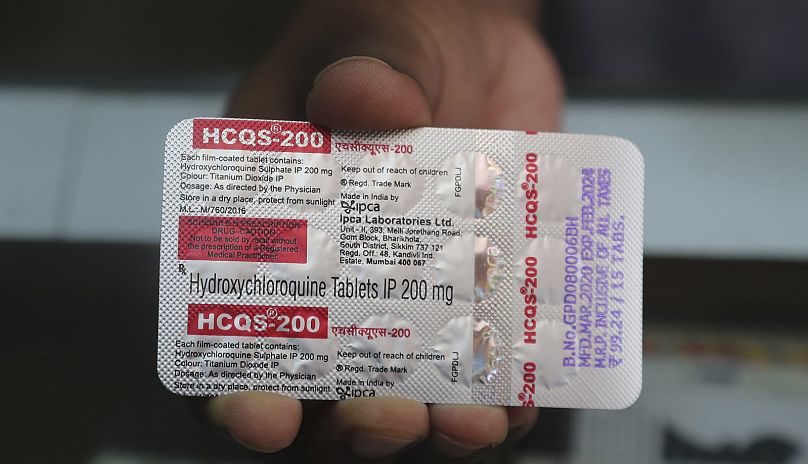

Hydroxychloroquine

"When I recommend something, they like to say 'don't use it.'" As late as July 28, Donald Trump was defending his promotion of an anti-malarial drug he believed was a promising therapy for COVID-19. Hydroxychloroquine arguably only came to prominence as a potential treatment after Trump sang its praises but has been widely discredited. Dr Cook is far less flattering towards the drug, telling Euronews: "It's not just ineffective; it's potentially harmful."

In a limited randomised study in the UK, in which 1,500 patients were given hydroxychloroquine, it was noted it had "no benefit," according to Cook. In fact, patients who had been prescribed the drug had stayed longer in hospital and "about 10 per cent were less likely to leave hospital alive within a month than patients who had the placebo."

The anti-malarial drug, when used in the high doses needed to have any effect on symptoms of the virus, is shown to have harmful effects on the rhythm of the heart, particularly in higher-risk older patients with potential heart complications. "It [hydroxichloroquine] has no role to play at present," argues Cook.

Fenofibrate

As with many drugs that have been connected with the new coronavirus, their original purpose is to treat other conditions but arguably have therapeutic uses in COVID-19 patients. The same can be said of the anti-cholesterol drug fenofibrate.

"There are 10s of drugs that have been shown to be beneficial in severe lung disease in the laboratory that don't translate to having benefit clinically," says Cook. This could be said of fenofibrate, he adds, calling a joint laboratory study by the Hebrew University in Israel and Mount Sinai hospital in New York "a distraction." The findings argue that COVID-19 leads to lipid deposits in the lungs that increase the severity of the virus, which fenofibrate was shown to halt in tissue samples in a lab.

According to Cook, there needs to be a thorough study to show the drug is safe in connection with the new coronavirus, with further larger studies to then prove its effectiveness. There is no evidence right now to prove it is beneficial to COVID-19 patients.

SNG001 (interferon beta)

Still in its infancy, a trial of a protein called interferon beta has already been hailed as a breakthrough in reducing the number of COVID-19 patients needing intensive care by the UK media. But given how early the results are, and how limited they are in scope, caution needs to be exercised.

The encouraging results of the SNG001 trial were prematurely released to a media frenzy, says Cook. Synairgen, a biotech company based in Southampton in the UK, was duty-bound to release the findings early for regulatory reasons with the stock exchange.

"If they are as significant as suggested, it will be really interesting and a drug that will need to be looked at further," he added.

The initial positive results of the study, which experimented with the protein being inhaled by patients using a nebuliser, showed a dramatic reduction of patients developing severe symptoms. However, only 100 patients were included in the trial which is far from significant. "It's a bit more interesting than fenofibrate," offers Cook.

Lopinavir and ritonavir

Antiretroviral drugs lopinavir and ritonavir are typically used together to treat people with HIV, helping to reduce the amount of the immunodeficiency virus in the blood and therefore the risks of developing AIDS. Scientists at the World Health Organization (WHO) included the two drugs in trials on hospitalised COVID-19 patients — which were part of a wider study called Solidarity that also looked at remdesivir and hydroxychloroquine — but discontinued it at the start of July.

"There are various studies going on internationally about those but they can wrap up because we know they're not effective," says Cook. As well as the Solidarity study, lopinavir and ritonavir were also included in the Recovery study — the first comprehensive study into COVID-19 treatments to be published that also included data on dexamethasone among others. The initial results found that the dual-use of these particular anti-virals didn't cause harm but they were ineffective against the virus.

Convalescent plasma

"A completely different approach is the convalescent plasma which, again, really is a drug treatment," says Cook. The treatment involves taking blood plasma from patients recovering from COVID-19 who have tested positive for producing antibodies, then using it in turn as a therapy to fight infection in patients sick with the virus.

Plasma is the focus of trials around the world, which have so far shown limited evidence that it might benefit patients. A trial by the University of Oxford reported that plasma therapy had no adverse effects on COVID-19 patients, showing one dose was sufficient to increase virus antibodies. However, it was only administered to 10 people. As with most of the drugs on the list, it will need to be subjected to the rigours of further research before it becomes a mainstream treatment.