in 1918, the Spanish flu claimed 50 to 100 million lives worldwide.

A pandemic swept through the US and Europe in 1918 killing, by some estimates, more than 50 million people.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It began between January and February in the United States when a flurry of people died after presenting symptoms of headaches, respiratory difficulties, cough and high fever.

A few months later, patients in France, Belgium and Germany had similar clinical symptoms and in May, a religious festival in Spain caused an outbreak of the same mysterious disease.

One of history's most devastating pandemics, the so-called Spanish Flu is seen as an important benchmark by historians who aim to learn lessons from past outbreaks in the face of the current coronavirus pandemic.

History repeating itself

"It feels like a time machine, everything we had investigated is becoming a reality day by day," Spanish historians Laura and María Lara Martínez told Euronews.

The sisters have been studying the 1918 flu for the past two years and the parallels between today's coronavirus outbreak and the 1918 Spanish flu were clear to them from the start.

In 1918, people said it would be a "minor cold" and yet it played out as in 2020 with health systems overwhelmed quickly, the two historians who are also co-authors of a book on the history of Spain, told Euronews.

The lockdown measures put in place over a century ago sound familiar today: theatres, schools and borders were all closed.

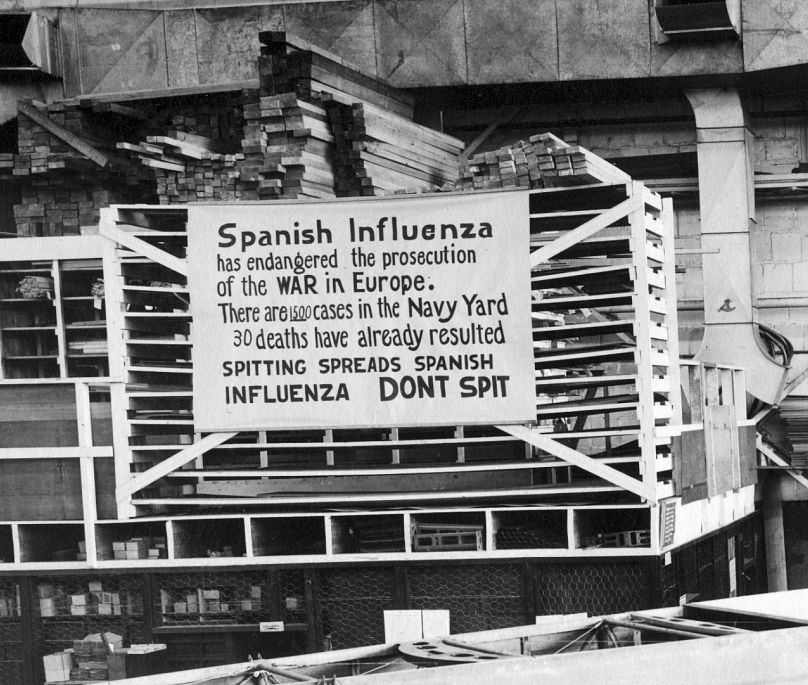

Public spaces, including telephones, were disinfected, historians say and in the United States, people could be fined up to $100 for not wearing a mask.

In 1918, it was quickly understood that crowds could cause further transmission.

"Lockdowns were put in place and progress was made in the application of preventive measures that had historically proven effective," historian Jaume Claret Miranda told Euronews.

This included hygiene measures and quarantining those suspected of being contaminated.

People did have "to fight against superstitions," Claret added. "For example, in Zamora the bishop called for mass that contributed to the effects of the pandemic and in Madrid, authorities did not cancel the San Isidro festivities."

Indeed the first wave of the outbreak in Spain took place just after the celebrations of the patron saint of the Spanish capital. A week after the celebrations, around May 22, newspapers said that everyone was falling ill with the flu, historians say.

The incident fuelled the naming of the new flu as "Spanish" even though patient zero is thought to have been at a US military training centre in Kansas.

Historians Laura and María Lara Martínez say that the 1918 flu could have originated even earlier in China or in France in 1917.

However, Spain's neutrality in the First World War meant that the journalism coverage of the new disease was more extensive.

'The mother of all pandemics'

Without hope of a vaccine or test, those fighting the 1918 pandemic faced different challenges and some expected summer temperatures to slow the virus' transmission.

The second wave of the epidemic, however, was more deadly than the first. In Spain it coincided with harvests and celebrations in September as well as the relaxation of lockdown measures, the Lara Martínez sisters said.

Outbreaks occurred the following winter, said Jaume Claret Miranda, who added that in some areas there was a third wave in the early 1920s.

"The end of the pandemic depended on each country: on the information and training of its specialists and the interests of its political class," says Claret.

But historians' "knowledge is very limited to the 'western world' and we do not know how this epidemic played out in many other parts of the world," he added.

Academics agree that the end of the pandemic occurred in 1920, when society ended up developing a collective immunity to the Spanish flu, although the virus never completely disappeared.

"Traces of the same virus have been found in other flu viruses," said Dr Benito Almirante, head of infectious diseases at the Vall d'Hebron hospital in Barcelona. "The Spanish flu continued to appear, mutating and acquiring genetic material from other viruses."

For example, the 2009 flu had genetic elements from earlier viruses, so older individuals were better protected than the young, he said.

This also occurred with the Spanish flu, with those over the age of 30 having better survival rates, said Laura Lara Martínez. It is speculated this is because the older generation lived with the so-called Russian flu in 1889 and 1890.

When does a pandemic end?

A pandemic ends when there is no uncontrolled community transmission, and cases are at a very low level, said Dr Almirante.

“In Europe this situation is coming [with the coronavirus] because the cases are easily identified and they can be tracked. If the situation continues in the coming weeks, the pandemic can be considered controlled."

“When people ask, ‘When will this end?,’ they are asking about the social ending,” Dr Jeremy Greene, a medical historian at Johns Hopkins University, told the New York Times.

During the Spanish flu pandemic, social fear varied according to the degree of information available and how countries were affected by the war, explains Claret. For example, England's field hospitals stayed up past the end of the war due to the outbreak.

But, in the end, "as often happens, when the effects subsided, people stopped worrying," Claret said.

Post-pandemic euphoria

The roaring 20s followed the Spanish flu pandemic and World War I.

"The population that managed to survive entered a phase of euphoria" including economically, said the Lara Martinez sisters.

It is part of human nature, they explain comparing it to "the dances of death" during the fourteenth century Black Plague. "Living with death, because it can appear at any time."

But also in this phase of post-flu optimism, totalitarian regimes began to emerge as the breeding ground for border control, individualism and the desire for autonomy.

"People's memory is short," Claret said. "However, it did leave a certain legacy at the scientific level and among specialists, confirming and adding knowledge to how these epidemics should be treated."

The main lesson from the past, Claret said is that "any measure" before the pandemic that was described as "exaggerated [is] later considered insufficient."