“Our stock levels of a medication that we rely on to be able to live and stay healthy is being affected by something that hasn’t even been proven yet," said Amy Baker, a 27-year-old who suffers from lupus about hydroxychloroquine.

Sufferers of the autoimmune disease lupus have had difficulties getting hold of lifesaving medication amid claims it could be used in the fight against coronavirus.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

At least 90 per cent of lupus sufferers in the UK are on hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malaria drug that is undergoing clinical trials as a potential treatment for COVID-19.

Lupus is a disease in which the immune system confuses and attacks healthy tissue as an invader like a bacteria or virus.

It is estimated around five million people worldwide suffer from some form of lupus.

There’s no cure for the illness which can cause fatigue, pain, inflammation, heart and kidney problems.

“At the worst, I feel like I can’t do anything like even breathing feels like it takes too much energy, it really knocks me out,” said Amy Baker, who was first diagnosed with lupus in 2007.

'We rely on it to be able to live'

Baker is a 27-year-old architecture student in the United Kingdom who said she had problems getting her prescription for hydroxychloroquine in March.

“I put in a prescription for it and I’m shielding so I wasn’t able to go and pick up the prescription myself. My neighbour went [and] she’d been told by the pharmacy that they were having difficulty getting it from the supplier so my prescription couldn’t be filled,” Baker said.

She called the pharmacy every day for a week until she could finally get her prescription.

Baker has already been hospitalised countless times for her illness and worries that if she cannot get the medication in the future, she could have a flare-up of the disease.

That could put her in the hospital during a pandemic, while she is considered more at risk for coronavirus due to her compromised immune system.

“It’s really frustrating because I know at the moment there’s no scientific evidence behind this,” Baker said, referring to the fact that currently there is little conclusive evidence to suggest the drug is effective against coronavirus.

“Our stock levels of a medication that we rely on to be able to live and stay healthy is being affected by something that hasn’t even been proven yet.”

Dr Michelle Petri, who is the director of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's Lupus Centre, said: “It is the only drug that improves survival of lupus patients.”

“Mortality increases fourfold if a lupus patient [stops taking the drug],” Dr Petri added.

A spokesperson for the UK Department of Health and Social Care told Euronews that there are no shortages of hydroxychloroquine in the UK.

“Central stockpiles of hydroxychloroquine are being used for clinical trials and this has no impact on the supply for patients prescribed the medicine,’ a spokesperson for the department said.

There is currently an export ban in the UK to protect stocks of the drug, but in late March, there was briefly a supply problem due to an increase in demand.

“It seems that there was an unexpected increase in demand for the medication hydroxychloroquine and this was partly it seems due to some doctors writing prescriptions for it for people concerned about COVID-19,” Paul Howard, the chief executive of Lupus UK, told Euronews.

People with lupus and other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis were also part of the increased demand.

“Many people were being advised around that time to self-isolate or shield themselves for a period of 12 weeks and so if they normally had a one-month prescription each time, they may have requested two months or three months to help them get through that period of shielding,” Howard said.

The supplies of the drug weren’t able to cope with the increase in demand.

Political hype over chloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 in March

Chloroquine is a drug that has been around since the 1940s to treat malaria and hydroxychloroquine is a less toxic derivative of it.

The drug has some serious side effects including headache, dizziness, nausea, and in some cases heart problems.

US President Donald Trump had touted the drug’s use against COVID-19 in mid-March, stating that it showed “very very encouraging early results”.

He said that the US would make the drug available “almost immediately”.

His comments coincided with the publication of a French study on March 20 of the preliminary results of the drug’s use on 24 French patients with COVID-19.

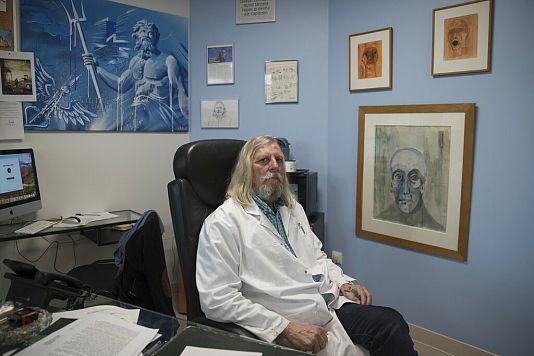

The study came from controversial doctor Didier Raoult and concluded that the treatment (of the small group of people) with hydroxychloroquine and an antibiotic showed a “reduction/disappearance” of the coronavirus in several patients.

The results made headlines worldwide even as doctors and scientists insisted the study was methodically flawed due to the lack of a control group and small sample size. The drug is part of many more serious clinical trials around the world along with several other antivirals.

Read more: Clinical drug trials starting in Europe include potential of chloroquine to treat coronavirus

French President Emmanuel Macron recently met with Raoult, calling him a “great scientist” and stating that hydroxychloroquine should be tested along with an antibiotic as a potential treatment, as Raoult had done.

But other studies have had mixed results, with one pre-print study in the US showing no reduction in the need for mechanical ventilation for hospitalised COVID-19 patients.

"An association of increased overall mortality was identified in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine alone," the researchers said, emphasising the need for "randomised, controlled" studies.

Restocking concerns in French pharmacies

The hype in France, however, created the same shortage problems as it did in the United Kingdom.

Noémie Villalonga is a 24-year-old musician living in Montpellier who says she was diagnosed with lupus when she was just 8 years old.

She was informed by her doctor in March to stock up on the drug she takes - chloroquine - to be sure they did not run out of stock.

“I telephoned six pharmacies which all told me they did not to have 'the right' to provide me with my treatment which was exclusively reserved for the hospitals for the patients of COVID-19,” Villalonga claims.

She says her illness handicaps her daily with fatigue and pain. She’s not concerned about not getting her medication though, stating that if it does help with COVID-19, they should use it.

“I believe that we are able to supply all the patients in need with adequate treatment,” she said. Villalonga received her prescription after two weeks of trying to get it at the pharmacy.

Johanna Clouscard is the president of Lupus France and has been working to make sure that the stocks are available to people who need the drug.

“There are still restocking concerns for some people. I just had a lady on the phone who has been waiting for her treatment for more than 15 days which is just absurd,” she wrote in an email to Euronews.

In a note on their website, pharmaceutical company Sanofi, which produces the drug, said in late March that “due to significant media coverage” they had many requests for hydroxychloroquine from medical professionals in towns and hospitals.

The French government authorised the use of hydroxychloroquine and other antivirals for COVID-19 patients in a March 26th law, while also protecting the drug so that patients with prescriptions such as people with lupus and other conditions could access it.

Ongoing drug shortage in the United States

Hydroxychloroquine is still, however, on a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug shortage list “due to a significant surge in demand,” a spokesperson for the agency told Euronews.

The agency is working with manufacturers to ramp up production of the drug and some pharmaceutical companies have donated doses for the US stockpile.

“I have been overwhelmed with patient requests to help them get their refills. Pharmacies are requiring me to do prior authorisations for patients further delaying their getting the drug. When they do get it it may just be a month or even less supply,” said Dr Petri a rheumatologist at Johns Hopkins University in the US.

The surge in demand was also influenced by an Indian export ban in late March on the active pharmaceutical ingredients for the drug, something that India later overturned under international pressure.

In an April 20th letter, the US Department of Justice cleared a wholesale drug company to distribute hydroxychloroquine from the US national stockpile for COVID-19.

“A big part of the concern in the longer term is around where the supply of this medication is going to come from,” said Howard at Lupus UK.

If proven to be effective against COVID-19, many fear that the drug shortage will get worse.

For now, patients are mostly able to find it “by trying multiple pharmacies,” said Dr Petri, but many fear that they will have to reduce their doses and risk their health if there continues to be supply issues.

“If it gets to the point where I start running low on supplies then it will become an anxiety problem, and stress and anxiety can cause a flare-up in lupus,” said Baker.