These past few weeks, the world’s eyes have been set on the fires ravaging the Amazon forest in Brazil and Bolivia.

Over the past few weeks, the world’s gaze has been fixed on the fires ravaging the Amazon rainforest in Brazil and Bolivia.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

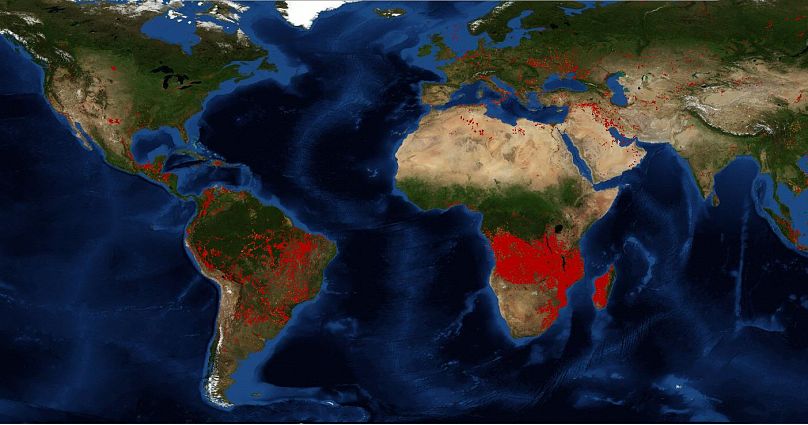

According to data from the Global Forest Watch, in August there have been more fire alerts in the Democratic Republic of Congo than in Brazil, where seven states have asked for help to battle the blazes.

Angola, Zambia, and Mozambique ranked just after the South American country, all of which have seen more fires than Bolivia after it accepted international aid.

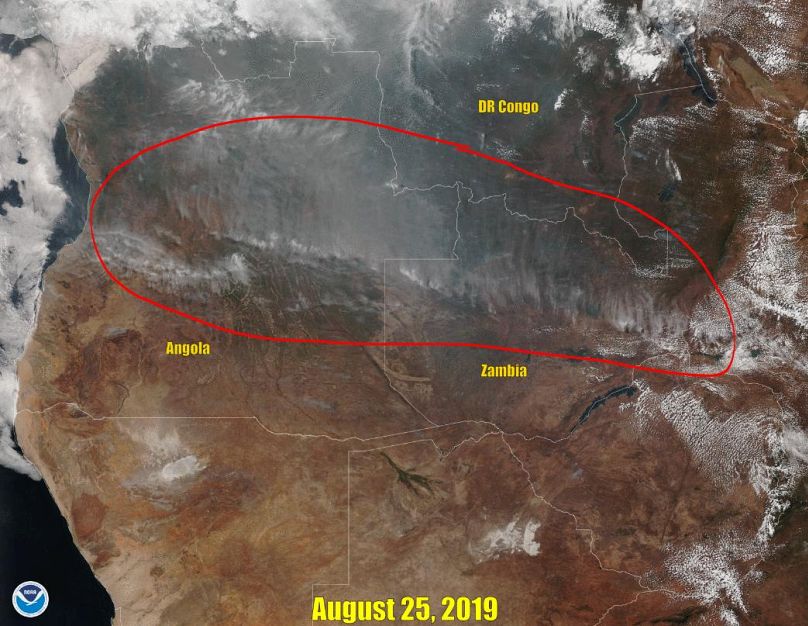

NASA satellites show a lot of fires in the African strip from Angola to Mozambique. Data from the European Union's Earth observation programme Copernicus shows that emissions from biomass burning are flagrant in this area.

Local African media have given little attention to fires in their own backyard, focusing more on what’s happening across the Atlantic.

In an interview with Euronews, Angola’s environment minister, Paula Francisca Coelho, said there were no wildfires in her country and qualified the information published on the African wildfires as “sensationalist” and “overdramatic”.

“We don’t have fires to control,” she said, though recognising that there are some active fires from the “practices of some communities preparing the ground for the next agricultural campaign".

'A very sensitive satellite'

Bob Scholes, professor of systems ecology at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, said one needs to be careful when analysing satellite images like those from NASA’s MODIS. “It’s a very, very sensitive satellite in space which can detect a fire as small as the garden fire you might make to burn rubbish in your backyard,” he said.

"Just because the number of fires seems far greater in Africa than it is in Brazil that doesn’t mean necessarily that the ecological damage is greater in Africa than in Brazil,” he said.

“It depends where they're burning and exactly how much area is burned, which you can't tell from the number of hot pixels.

“The second issue is if you look at the distribution of where the hot pixels are in Africa at this time of year, there are almost all in savannahs and not in the rainforests.”

Why can't fires in Africa be compared with those in the Amazon?

Experts say that context is important when analysing images taken from space.

“Satellite images, as impressive as they may seem, tell only part of the story,” Mark Parrington, a Copernicus researcher, said in a tweet.

Parrington told Euronews when comparing figures from the last 17 years on fire activity in southern, tropical Africa from late May to early October, this year's figures suggest there are fewer blazes than average.

This is a natural cycle in the Savannah — much of the vegetation that burns in the dry season grows back in the rainy one, he said.

"It's a relatively carbon-neutral process, and it's something that does happen every year, and in fact, what we see with the fire season is that it oscillates between northern tropical Africa and southern tropical Africa every six months or so," Parrington said.

"So at the end of October, when these fires will eventually die down and disappear, there will be more and more fires in northern tropical African countries."

Scholes points out that while fires are extremely damaging to the biodiversity of a tropical forest like the Amazon, "the savannahs have to burn, it's part of their evolution, they've burned over the last seven million years and there's nothing unusual about it."

Antti Lipponen, a researcher at the Finnish Meteorological Institute, told Euronews that carbon monoxide emissions from the burning of African biomass in August have so far been approximately 1.5 times higher than in Central and South America. But these figures are normal for this period of the year, he noted.

In the Amazon, as in Central Africa, scientists also expect fires from August to September during the beginning of the dry season. But this year deforestation seems to have disrupted the balance between vegetation and the carbon cycle.

Parrington, meanwhile, points out that emissions in Africa are relatively carbon-neutral, so they do not have as much of a direct impact on the climate, unlike those in the Amazon. Though this also depends on the type of vegetation being burned.

Parrington says air circulation patterns also need to be taken into account. Studies indicate that smoke and particles from fires in Central Africa travel across the Atlantic Ocean to the Amazon and act as fertiliser.

Africa is not a single country or one single fire

Although forest fires are an ancient practice during the dry season in tropical African countries, it is difficult to understand their impact globally.

Angola realised that in recent years the country had lost a large area of native forests due to uncontrolled fires of various origins, including hunting.

**"**While the main motivation was clearing the land, preparing for the next cultivation, and also to provide new growing grass for cattle, there is also the purpose of hunting," Amilcar Salumbo, an Angolan agronomist, told Euronews.

"And this appears to be the one causing the most damage, due to the increasing number of people dedicated to this practice in rural areas."

Salumbo believes that more control of this phenomenon is needed, as vast areas of the territory are considered no man's land and are prone to be affected by fires.

"Also, anyone can start a fire, and if it is at a remote area it can spread out of any kind of control," he adds.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, journalist Jean Hubert Bondo says that fires are not only related to agricultural practices but are also the product of criminal acts and armed conflicts. "These fires also devastate our equatorial jungle, which is the second in the world after the Amazon," he laments. "A forest that has already been the victim of deforestation and industrial exploitation."

For Amkela Sidange of Zimbabwe's Environmental Management Agency (EMA), climate change is disrupting the fire season, which the country has set by law from 31 July to 31 August.

"Our rangeland now dries much faster. Therefore, fires occur outside of what we call fire season," he explains. The problem, he points out, is that people continue to light fires without realising that fire season starts much earlier.

EMA's technical department provides firefighting training to local communities.

But Sidange wants to make it clear that Zimbabwe is not the Amazon: "We cannot compare our rangeland makeup to the think [vegetation] area we have in the Amazon. In Zimbabwe, it is still possible to control the fires."

Watch Euronews' social media news desk The Cube report on the subject in the video player above.